#10: Orlando (1992) – dir. Sally Potter

In Sally Potter’s gender-bending adaptation of the novel by Virginia Woolf, Tilda Swinton plays the title character, a man whose tale begins in 1600 at Queen Elizabeth’s court. The viewer recognizes right away that the film is taking a slightly different approach to storytelling by having Swinton directly address the camera, a technique that is employed throughout the film. This acknowledgement of the audience and of the cinematic apparatus does not detract from the film, although it makes us more aware that we are watching a production created with actors, costumes, set designers and makeup artists. (Continue reading if you choose, but there are spoilers ahead…)

I don’t believe that the film could have starred anyone but Tilda Swinton. Like the character Orlando, Swinton has an androgynous quality to her, a combination of feminine and masculine in her appearance that she can use to transform herself into any kind of character. No matter the sex of her character, her eyes transfix you.

In one of the film’s more amusing touches, Quentin Crisp was cast as Queen Elizabeth. He’s not in the film for very long, but he’s quite good while he’s there. The most important aspect of the Elizabeth character is the bit of dialogue when she informs young Orlando that he is being allowed to take up residence in a great house (it helps to be a favorite of the queen!), but he must promise never to grow old.

Orlando’s story is not confined to the year 1600. True to Queen Elizabeth’s request, Orlando never ages a day, although his tale lasts for many centuries. In 1650, he is seen as a young lord in love with poetry yet unable to create any good examples of his own, making other poets scowl at his lack of talent. This artistic desire speaks to an inner longing for achievement and acceptance.

In 1700, Orlando is sent as an ambassador to a foreign nation. During this trip he meets a royal played by Lothaire Bluteau, a French-Canadian actor I know best for playing four different characters in standalone episodes of “Law & Order: Special Victims Unit” and “Law & Order: Criminal Intent” over the past fifteen years. I wish Bluteau had had more screen time; he had a strange yet undeniable chemistry with Swinton, although they share little more than conversation, some intense stares and one brief, platonic hug.

It is during this stay abroad that Swinton’s character begins to undergo changes both mental and physical. (The hair you see is one of those 18th century wigs favored by men of nobility.) Perhaps it is the subtle influence of Bluteau’s “Khan”; certainly the war they both fight in for the independence of the foreign country affects Orlando’s understanding of what it means to be a man.

…and so, the next morning after a great battle, Orlando wakes up to find he has turned into a woman. This is totally believable as played by Swinton, who assures us as she stands naked before a mirror that she is the “same person, no difference at all. Just a different sex.” The body has changed but the inner spirit remains the same. The main difference is in how Orlando will react to being a woman in a man’s world.

Sandy Powell’s costumes now switch from the elegant menswear of 1600-1700 to the elaborate, flowing gowns of 1750. As Orlando floats through her English country house – the same house given to her 150 years earlier by Queen Elizabeth – her white dress forms a striking comparison with the sheets covering the furniture. They are all temporary sheaths for the beauty underneath.

Stifled by society and by the men who care more about her looks than about her opinions, Orlando escapes through a maze and ends up in 1850. The maze is a useful cinematic device, allowing Orlando to travel a hundred years by the time she is out on the other side.

While lying in the grass, inconsolable, a love interest literally drops into Orlando’s lap: Shelmerdine (Billy Zane), an American who falls off of his horse in a scene not unlike Jane’s first encounter with Rochester in Jane Eyre. In an entertaining reversal, instead of Orlando being a damsel in distress, it is the male character who is in trouble. Even more interesting, as soon as Shelmerdine lands on the ground, Orlando asks him quite boldly if he would like to marry her. It does not occur to Orlando to stick to Victorian social graces.

I can’t say that Billy Zane is much of an actor, but he has a certain cinematic presence that makes sense for this film. The length of his hair, his billowing shirt, something about his facial features (his eyes and perhaps his smile?) and even his character’s name (“Shelmerdine”) all display a prettiness that is somewhat feminine. After all, the blurring of the division between male and female is what the film is all about. The “female gaze” of both the Orlando and the film’s director (Sally Potter) objectify Shelmerdine in his scenes, the opposite of the usual male-female dynamic in movies.

Although their love cannot last – maybe it was only a passing attraction to begin with – the brief romance between Orlando and Shelmerdine results in a child. As was the case all throughout the film, the bloom of youth stays with Orlando as she lives through England’s wars in the twentieth century, pregnant the whole time until we see her once more in 1992, the year that the film was released.

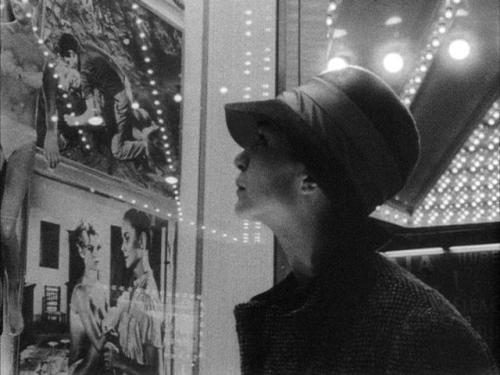

At the end of the film, Orlando’s daughter is around ten years old and presumably the little girl will grow up like a regular human. (One wonders if she ever asks Mom why they are living in an Elizabethan-era estate.) In the modern era, Orlando’s wardrobe makes the point that in 1992 she can wear whatever she wants and her character will not be defined by sex, gender, relationships (or the lack thereof) or clothing. It seems that by the end of the film Orlando has finally found some peace; maybe now as a mother and as a writer (the above image shows her in her agent’s office after she has written the story of her existence, which is awaiting publication) she can find contentment and age like a mortal. I would not say that I loved Orlando, which is often disjointed and substitutes technical accomplishments for emotionality (although, as you know, I do love Tilda Swinton), but it is still a film well worth watching.