Today is International Women’s Day, and because this blog is all about promoting the wide array of films made by women behind the camera, here are twenty films (both features and shorts) from a variety of eras, genres and cultures, all viewable instantly thanks to YouTube, other streaming services and cable TV on demand.

Suspense (1913, dirs. Phillips Smalley and Lois Weber) – YouTube

“Lois Weber and Philip Smalley’s Suspense might only clock in at barely over ten minutes, but for the earliest run of home invasion films, it is by far the most memorable, utilizing many cutting-edge camera tricks and establishing a seriously unique visual style along the way. […] The story revolves around a young wife, played by Weber, who lives on the outskirts of town. One day, her husband goes off to work. Unbeknownst to Weber’s character, the housekeeper chooses exactly that day to resign due to the remote location of the home. Due to this stroke of bad luck, the wife is left alone in the house, which is bad news because it’s the exact day a very random grifter shows up to terrorize her. After locking eyes with the villain, she calls her husband for help, and he frantically rushes home while the bad guy advances on the young wife and her child.

“When discussing this film, one of the most important details is that the camera work on display here is incredible. The memorable moments are almost too many to count. When the wife very first senses something suspicious is happening, she leans slowly out the window, only to see the vagabond look suddenly up at her in a moment that still carries chills to this very day. Her phone call to her husband splits the screen into 3 triangles, one of her, one of her husband, and one of the villain methodically breaking into the house. When the husband steals a car to rush to her side, the police follow him and he peeks back at them through his passenger side mirror. While many of the camera tricks had previously been utilized in other films, the hurried pace at which they cut together in Suspense is something new entirely.” (Sara Century, Syfy)

Mabel’s Blunder (1914, dir. Mabel Normand) – YouTube

“Mabel Normand was the first major female comedy star in American motion pictures. She was also one of the first female directors in Hollywood, and one of the original principals in Mack Sennett’s pioneering Keystone Comedies. Mabel’s Blunder (1914), made two years after the formation of the Keystone Film Company, captures Normand’s talents both in front of and behind the camera.

“Mabel’s Blunder features Normand as a stenographer secretly carrying on a romance with her boss’s son – played by Keystone regular Harry McCoy. She becomes jealous when she sees McCoy taking up with an attractive woman (Peggy Page), and disguises herself as a chauffeur to spy on them as they rendezvous at a restaurant. At the same time, Normand’s younger brother disguises himself as his sister, and finds himself the subject of amorous attentions from her boss (Charles Bennett). In the end, Mabel discovers that her perceived love rival is actually McCoy’s visiting sister, and everything is sorted out for the better.

“Besides trading on the comedy staples of mistaken identities and misunderstood intentions, Mabel’s Blunder also features a double-dose of another standard of farce: gender-impersonation, with Mabel disguising herself as a man, and the unidentified young actor* playing Normand’s brother donning drag to impersonate his sibling. Normand had been impersonating males for comic result ever since her Biograph days. An early Keystone, Mabel’s Stratagem (1912), had also featured Normand as an office worker who is fired when her boss’s wife feels her husband is being too affectionate to his stenographer, and insists that he hire a man for the job instead. Mabel later dons male drag and gets the job – only to find herself now becoming an object of flirtation from the wife.” (Brent E. Walker, Library of Congress)

*Note: Al St. John played Mabel Normand’s brother, as per the IMDb listing.

The Ocean Waif (1916, dir. Alice Guy-Blaché) – YouTube and Kanopy

“Alice Guy-Blaché (French, 1873-1968), the world’s first woman film director, made films for Gaumont in Paris (1896-1907), then had her own studio, the Solax Company in Fort Lee, New Jersey (1910-1914). After Solax ceased production, she became a director for hire and went to work for The International Film Service, owned by William Randolph Hearst. The plot of The Ocean Waif adheres closely to the Hearst agenda: a romantic story, plenty of pathos but no brutality, a likeable hero and an innocent young woman, and a suspenseful plot with a dramatic and happy ending (‘the Mary Pickford school of narrative’). Blaché’s parody of the Pygmalion-type love story gives equal screen time to each lover’s point of view, but also skewers conventional class tropes. Doris Kenyon stars in the title role of an abused young woman who finds safety and eventually love in the arms of a famous novelist.” (Kanopy)

Craig’s Wife (1936, dir. Dorothy Arzner) – YouTube

“Columbia, to be quick about it, has been able to do quite well with [George] Kelly’s drama of domestic infelicity. Mary McCall Jr. has retained all that mattered of the original lines, Dorothy Arzner—Hollywood’s only woman director—has given them a full hearing without sacrificing camera mobility, and a supple cast headed by Rosalind Russell and John Boles has translated the whole into a thoroughly engrossing photoplay which has a point to make, keeps it constantly in view and drives it home viciously at the end. ‘People who live to themselves are generally left to themselves.’ That is Mr. Kelly’s story and Craig’s Wife makes the best of it.

“Since ten years have passed since the play was shown here, a brief reminder of its materials may be in order. Harriet Craig was a woman with a purpose—she wanted a home, symbol of permanence, position and security. To attain it she married and to retain it she had to obtain full control of her husband, modeling him into just another bit of house furnishing. Always it was the house that counted; dustless, friendless, a temple of material things which, if she guarded well, would be hers for the keeping.

“…The entire weight of the drama depends upon the malign effectiveness of its central character and Miss Russell, here enjoying her first real opportunity in Hollywood, gives a viciously eloquent performance. Mr. Boles, although sincere and natural in the rôle of the husband, is unable to keep his audience from jeering in that dramatically feeble moment of rebellion when he breaks crockery and spills cigarette ashes. That, admittedly, was more Mr. Kelly’s fault than Mr. Boles’s. The other players are uniformly splendid, with special mention of Alma Kruger as the aunt, Elizabeth Risdon as the housekeeper, Nydia Westman as the maid. Billie Burke as the flower-gathering neighbor, Thomas Mitchell as Fergus Passmore and Robert Allen as the niece’s suitor.” (Frank S. Nugent, The New York Times)

Ritual in Transfigured Time (1946, dir. Maya Deren) – YouTube

“Ritual in Transfigured Time (1946) silently follows Rita Christiani’s perspective as she enters an apartment to find Maya Deren immersed in the ritual of unwinding wool from a loom. Deren includes another expression of the external invading the internal with a strange wind that surrounds and entrances her as she becomes transported by the ritual. Ritual in Transfigured Time links the looming ritual with the ritual of the social greeting. Christiani enters a party, meets and greets, moving throughout the crowd like a dancer. Her movements become increasingly expressive and fluid, the ritual becomes a performance. Key themes in this film are the dread of rejection and the contrasting freedom of expression in the abandonment to the ritual.” (Wendy Haslem, Senses of Cinema)

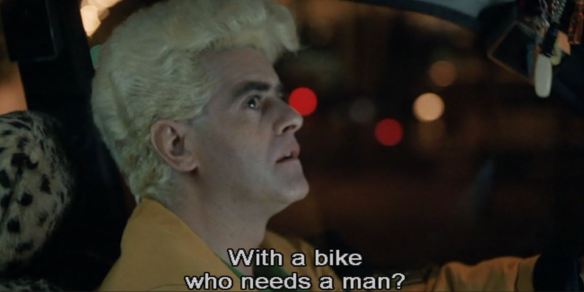

The Hitch-Hiker (1953, dir. Ida Lupino) – YouTube

“With no major female characters, Ida Lupino’s 1953 film The Hitch-Hiker is somewhat idiosyncratic in her feature film directing career. Considered a director with a strong female identity, Lupino shows she can handle a gritty all male thriller just as skillfully as one of her mentors, Raoul Walsh. She was also admittedly an admirer of Allan Dwan, Fritz Lang and cinematographer George Barnes. The Hitch-Hiker, made in 1953, tells the story of two weekend fishermen, Roy Collins (Edmund O’Brien) and Gil Bowen (Frank Lovejoy) who graciously but unfortunately pick up hitchhiker Emmett Myers (William Talman). Myers turns out to be a psychopathic mass killer who forces the men to take him across the border to Mexico. The remainder of the film is a claustrophobic ballet of survival between the two hostages and the killer. Lupino keeps the trio in close quarters throughout the film enforcing the fear that escape is impossible. Much of the time the three men spend in cars and small backrooms, yet even in the openness of the Mexican desert Lupino’s camera confines the characters’ space.

“From the opening sequence, Lupino keeps you on the edge of your seat with the threat of violence about to explode at any moment. Filmed by the magnificent cameraman Nicolas Musuraca, it is filled with stark, contrasty black and white imagery that enhances the moody aridness of the brutal desert heat. What is amazing is how much Lupino accomplished with such a low budget, both in front and behind the camera. Like all of Lupino’s directed features, this was a no-frills production.” (John Greco, Twenty Four Frames)

Mister E (1960, dir. Margaret Conneely) – YouTube

“A domestic black comedy, Mister E expresses some of the edgier mischief and discontent that women of mid-century America could rarely express openly. This short film narrates the revenge acted out by a young wife, left at home while her husband is at a card game; by staging a rendezvous with a mannequin, this woman provokes an eruption of jealousy and violence before bringing about the desired marital tenderness.” (Chicago Film Archives)

The Heartbreak Kid (1972, dir. Elaine May) – YouTube

“Scripted by Neil Simon, May’s most critically and commercially successful film as director induces both laughs and shudders in its acerbic portrait of male egotism, selfishness, and cruelty. The Heartbreak Kid opens as nebbishy salesman Lenny (Charles Grodin) hits the road with his new bride Lila (played by May’s daughter Jeannie Berlin, who received an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actress) for their honeymoon in Miami Beach. Unconscionably annoyed by Lila’s whiny neediness before they reach the first rest stop, Lenny realizes that he’s made a mistake — and when he sets eyes on blonde socialite Kelly (Cybill Shepherd) at their beachfront hotel, he abandons the sunburned Lila in her room and sets out in pursuit of the shiksa dream goddess. ‘A first-class American comedy’ (Vincent Canby, The New York Times); ‘The culminating work of Hollywood’s Jewish new wave[,] as well as a hilarious riposte to [Mike Nichols’] The Graduate … a masterpiece of social pathology’ (J. Hoberman, The Village Voice).” (2018 Toronto International Film Festival)

The Slumber Party Massacre (1982, dir. Amy Holden Jones) – YouTube

“The Slumber Party Massacre was conceived as a parody of the slasher and its gender dynamics (as they were interpreted in the early ’80s, of course) by screenwriter Rita Mae Brown, a lesbian activist and novelist. In the years that followed, Brown complained that her satirical script was stripped of its satire by a studio that was more interested in luring in the usual horror movie target market of teenage boys than in making some kind of feminist commentary. But her complaint misses the mark. Maybe this isn’t the movie that Brown envisioned when she was writing it, but under the earnest direction of Amy Holden Jones, The Slumber Party Massacre turned out to be a whip-smart slasher that totally works as both a genuinely well-done cheapie slasher film and as a twist on the standard slasher psychology. There is still plenty of satire here, but it’s affectionate, gentle satire—not really genre-busting, as Brown perhaps intended it to be. Indeed, its cleverness actually makes it much more fun than many inferior slashers, and in the end it’s more likely to bring new fans into the fold than convince anyone that the whole genre is worthless. The Slumber Party Massacre gives slasher fans every single thing they could possibly want from this genre, with a ton of bonus wit that makes viewers feel smart and the film feel like a ton of fun. And that’s something you just don’t get every day.” (Megan Weireter, NotComing.com)

Little Women (1994, dir. Gillian Armstrong) – Netflix

“‘Some books are so familiar reading them is like being home again,’ Jo March observes in the new film version of Louisa May Alcott’s classic novel. She’s talking about Shakespeare, but we all know Little Women is a book like that, one of the most seductively nostalgic novels any child ever discovers. As the gold standard for American girlhood, it lingers in our collective consciousness as a wistful, inspiring memory. Ladies, get out your hand-hemmed handkerchiefs for the loveliest Little Women ever on screen.

“Gillian Armstrong’s enchantingly pretty film is so potent that it prompts a rush of recognition from the opening frame. There in Concord, Mass., are the March girls and their noble Marmee, gathered around the hearth for a heart-rendingly quaint Christmas Eve. Stirring up a flurry of familial warmth, Ms. Armstrong instantly demonstrates that she has caught the essence of this book’s sweetness and cast her film uncannily well, finding sparkling young actresses who are exactly right for their famous roles. The effect is magical. And for all its unimaginable innocence, the story has a touching naturalness this time.

“…The direction by Ms. Armstrong, who long ago summoned memories of Little Women with My Brilliant Career (1979), is sentimental without being saccharine. And the film maker is too savvy to tell this story in a cultural and historical vacuum. So this Little Women has ways of winking at its audience, most notably when the tomboyish, intellectually ambitious Jo March reveals that she has cut off and sold her mane of hair. ‘Jo, how could you?’ wails Amy. ‘Your one beauty!’ Well, this Jo is Winona Ryder and the joke is that she has beauty to spare, along with enough vigor to dim memories of Katharine Hepburn in the now badly dated 1933 George Cukor version. Ms. Armstrong reinvents Little Women for present-day audiences without ever forgetting it’s a story with a past.” (Janet Maslin, The New York Times)

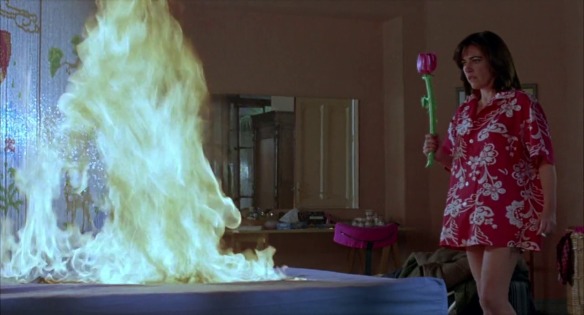

Fire (1996, dir. Deepa Mehta) – YouTube

“In this film, Radha is unwavering in her devotion to her husband, Ashok, despite their sexless arranged marriage. For 15 years, she has been the consummate Indian wife, while Ashok, under the guidance of a spiritual leader, is attempting to rid himself completely of any form of desire. Meanwhile, Ashok’s brother Jatin has brought home his new wife, Sita, but is unwilling to give up his relationship with his Chinese girlfriend. Added to the mix are Biji, Ashok and Jatin’s infirm mother, who keeps a watchful eye over the family. Slowly, Sita’s presence causes the threads that held the family together to unravel.

“Each member tries to hang on to a semblance of allegiance to the deeply rooted traditions of Indian family life, while at the same time seeking expression for their own personal needs and desires. Unable to woo her new husband, the young and feisty Sita is the first to question the order of things. Her doubts are contagious, and soon Radha’s devotion begins to waver, too. Deprived of their husbands’ affections, the two women draw closer together in ways neither imagined.

“Director-writer Deepa Mehta has captured the shifting landscape of the entire Indian subcontinent, where both men and women are caught in the immense tension between the continuity of the extended family and the desire for greater freedom and independence. Lusciously photographed and passionately told, Fire ignites the senses and the emotions.” (Jinah Kim, Harvard University Department of History of Art and Architecture)

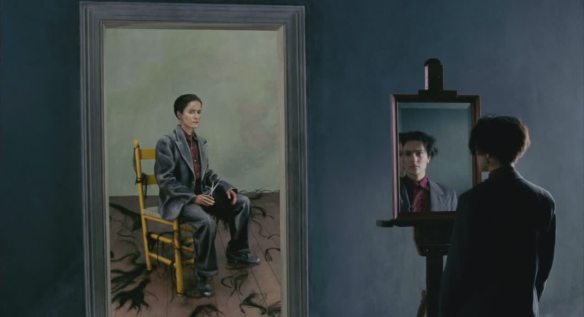

Frida (2002, dir. Julie Taymor) – Showtime (streaming or on TV via the Showtime on Demand channel)

“The tormented, turbulent and passionate life of legendary painter Frida Kahlo, an artist of unique and bountiful talent – and an icon of suffering who has become known in Mexico as the saint of the afflicted – was too big to fill a single canvas. She suffered for her art and made art out of suffering, merging art and life in autobiographical canvases that mixed Mexican folk art with European surrealism. Hard to capture on film. But Lion King director Julie Taymor, an artist with her own fame for stylish and audacious visuals, has knocked herself out condensing the breathless melodrama of that life into a film of overwhelming artistry, beauty and impact. The result is Frida, the greatest movie about an artist since Vincente Minnelli grafted the psychological turmoil of Vincent Van Gogh onto the screen in Lust for Life.

“Belying its $12 million budget, the film is a lush, sensuous triumph with wonderful music, sumptuous cinematography that matches [Salma] Hayek’s beauty, and a striking use of puppets, computer animation and collages that come to life, in locations ranging from the colonial city of Puebla and the Aztec ruins of Teotihuacan to La Casa Azul, Frida’s famous villa in Coyoacán, named for its azure blue walls. The film begins and ends in that house, with the stench of gangrene already upon her as her first exhibition is being planned in Mexico City. Forbidden by her doctor to leave her bed, Frida is carried through the streets by mariachis in the same four-poster bed where she taught herself to paint lying in a horizontal position. In flashbacks, we see her as a spunky teen, dressing like a boy to scandalize her parents; the horrific accident that left her crippled for years; and the bizarre relationship with Diego that began as fellow comrades fighting capitalism and led to an eternal love affair that brought her more torture than joy. Diego is played by Alfred Molina as a mad, excessive and violent hedonist with lusty appetites for food, fiestas and fornication. (On the morning after their wedding, Frida awoke to find Rivera’s ex-wife cooking his favorite mole sauce in her kitchen. The woman stayed for years!) By all accounts, Frida was a better painter, but in the early stages of their life together, she sublimated her own talent to be his muse and inspiration and play a supplemental role in his career.

“…Ms. Taymor manages to piece together the salient facts of a life charged by sex, politics and art with coherence and a strong allegiance to narrative, but at the same time she rubs the material with a brilliant patina of her own. Straightforward biography is superimposed with visuals, as the paintings of Kahlo and her husband Diego appear and dissolve. Kahlo devoted herself to the Buddhist theory that pain can produce beauty (‘I took my tears and turned them into paintings,’ she declared in her diaries), and Ms. Taymor knows the tricks of perspective to take all of these elements closer to Frida’s state of mind, in which art and life merge cinematically. The transition from Frida’s psychological pain to the surrealism with which her conscience finds its way to her canvases is daring but not pretentious, and there is always something amazing and luscious to look at. I have seen it twice, and I found awesome discoveries both times. I have heard this movie called everything from a masterpiece to pure kitsch – which would probably have amused the wicked, fun-loving Frida immensely. Julie Taymor’s vision of Frida Kahlo’s life and art is as prankish as its subject – an artful echo of a lyrical, sensual, voyeuristic, anarchic slapstick tragedy.” (Rex Reed, The New York Observer)

Sabah (2005, dir. Ruba Nadda) – YouTube

“In Arabic, sabah means ‘morning,’ and Sabah’s main visual metaphor is of a delicate flower stretching toward the morning sun. Played by one of Canada’s finest actors, Arsinée Khanjian, Sabah is a dutiful daughter in a close-knit, immigrant Muslim family who lives at home taking care of her mother. But something’s missing: having resisted an arranged marriage, she’s never known love. On her fortieth birthday her over bearing brother Majid (played by Jeff Seymour), gives her a photograph of herself as a little girl in Syria, standing by the seashore with their now deceased father. The photograph awakens a remembrance in Sabah, and like the influential Syrian filmmaker Mohammad Malas, Nadda uses memory as a formal device to lead Sabah toward her future.

“Fuelled by this long forgotten joy and sense of freedom, she secretly goes to a local pool. There, she meets Stephen, a Canadian non-Muslim (played by Shawn Doyle), who accidentally grabs her towel, her only protection in this foreign environment. Sabah takes a courageous first step toward her own happiness by gradually starting to talk to him. In doing so, she sets off a chain of events that eventually affects her entire family.

“…Federico Fellini once said, ‘The only visionary is the realist because he bears witness to his own reality.’ Nadda writes what she knows. Like traditional Arab writers, she weaves together aspects of her own life with those of her characters, mixing dream into reality. Born in Montreal in 1972, of Syrian and Palestinian parents, Nadda moved around Canada a lot while growing up. From those experiences, she says, ‘I developed an acute sensitivity and empathy. I’m able to identify with people and put myself in their shoes. And I can take that and put it in a film.’ Briefly living in Damascus at the age of sixteen, Nadda learned just how precarious a girl’s freedom in a Muslim country is: she was almost married against her will. From that moment on she says, ‘I enveloped life. When you’ve almost had your independence taken away from you, you never want to go through that again.’ Once, on the bus during her last year at York University she saw a Muslim woman in a burqua, completely covered head to toe; only her eyes were visible. Nadda wondered about the woman’s sexual urges and what would happen if she fell for the ‘wrong’ man. That moment gestated within her, slowly forming into what would eventually become Sabah.” (Noelle Elia, POV Magazine)

Mamma Mia! (2008, dir. Phyllida Lloyd) – Netflix

“Hanging a tale of a woman whose daughter might have been fathered by one of three attractive men on a bunch of ABBA songs sounds simple, but its simplicity is as deceptive as the masterfully crafted songs themselves. [Meryl] Streep plays Donna, a former singer, who has raised daughter Sophie (Amanda Seyfried) alone at a fading resort on a remote Greek island. Sophie finds her mother’s diary from 20 years earlier and discovers that there are three men who might be her father. About to be married to boyfriend Sky (Dominic Cooper), she sends invitations to the celebration to all three on behalf of her mother but without telling her. Pierce Brosnan, Colin Firth and Stellan Skarsgård, as the possible dads, show up on the island where Donna is readying the wedding, helped by her two best pals (Julie Walters and Christine Baranski). The scene is set for songs, dancing and romance, all staged brilliantly, with many energetic and colorful performers, and beautifully shot.” (Ray Bennett, The Hollywood Reporter)

The Innocents (2016, dir. Anne Fontaine) – Netflix

“During a bitterly cold winter, tucked away in a provincial Polish village just after World War II, seven nuns are secretly pregnant. While the women sing in their barren church with faded blue stucco walls, a shriek echoes in the abbey, prompting one mischievous sister to race through the snowfall and into the woods for help. Some orphans lead her to the French Red Cross. There, she catches the attention of a young woman doctor, Mathilde (Lou de Laâge), who at first refuses to help the nun, following protocol, eager to please her male superiors with her hardened obedience. But the sight of the nun praying in the snow shakes some ice from Mathilde’s heart, and she comes to the rescue of another nun birthing a breech baby. Talk of science and faith dominate the conversations of Mathilde and French-speaking nun Maria (Agata Buzek). But both are struggling — Maria with her belief in God after the Russian soldiers who seemed meant to save them imprisoned them as prostitutes instead, Mathilde with the belief that she could ever be a respected woman of science in a male-dominated world.

“…Now, the idea of a woman’s loss of freedom isn’t necessarily fresh territory. Neither are nuns in a postwar Polish winter; Pawel Pawlikowski’s spare tale Ida (2013) already did a fine job with that, with a black-and-white palette of shadows that perfectly captured the isolation of both the season and the religious calling. But The Innocents departs with a surprisingly warm tone in both color and feeling. A calming natural light ribbons through every cold landscape, catching the almost translucent white skin of the nuns and the billowing navy and black of their habits — very Vermeer.” (April Wolfe, LA Weekly)

Raw (2016, dir. Julia Ducournau) – Netflix

“It’s the cannibal movie that caused people to faint at a film festival – this is what people talk about when they talk about Raw, the extraordinary body-horror parable from French director Julia Ducournau. The incident, which happened at last year’s Toronto International Film Festival, might cause folks to view this as some sort of cinematic dare, a splatter shocker designed to test the limits of the scary-movie marine corps. Consider this a disclaimer, and a reclamation: The story of a young woman (Garance Marillier) who develops a taste for certain off-the-menu delicacies is indeed intense. It’s also after much bigger game than merely thrilling folks who’ve studied Fangoria photo spreads with Talmudic-scholar fervor. Smelling salts are not required, but the ability to recognize a near-perfect movie when you see it most certainly is. If Get Out reminds folks that you can smuggle intelligent social commentary and timely conversation-starters in to theaters via explosive genre packages, then Ducournau’s feature debut doubles down on the notion. In terms of the female-body politic, it’s an art-horror dirty bomb.

“…Ducournau has referred to her movie as a coming-of-age story, and you can see this waifish character go from awkwardly tottering in high heels (a shot that spells out the movie’s ideas on femininity drag; don’t even ask about the Brazilian waxing sequence) to aggressively asserting herself over 99 blood-flecked minutes. Girl, you’ll be a man-eating woman soon, and though references to bulimia and trichophagia suggest control issues run psychologically amuck, Justine also discovers a sense of empowerment in this taboo line-crossing. She begins to take ownership of her body by consuming others’.

“None of which should suggest that Raw is simply a grad-school term paper smothered in gore. Ducournau knows how to make the vocabulary of horror filmmaking either finesse or bludgeon with a frightening degree of facility. Few movies have used pacing and composition to such an effective degree in the name of XX-centric dread (the film owes as much to Roman Polanski’s Repulsion as it does to the cinema of repulsion), or understood how to employ color so effectively – from a seven-minutes-in-heaven encounter involving blue and yellow paint to the crimson drop on a white lab coat that signals a Type-O deluge. There’s a hallucinogenic quality to the deadpan scenes of Justine coming to grips with this personal channeling of passion and perversity, and a shocking aspect to the carnage that feels invasive in a way most shock artists can’t conjure. You never get the sense that you’re not watching a master at work, regardless of how scant Ducournau’s filmography is. She is the real thing.” (David Fear, Rolling Stone)

The Party (2017, dir. Sally Potter) – Hulu

“In Potter’s pitch-black, claustrophobic comedy, a stellar ensemble including Kristin Scott Thomas, Patricia Clarkson, Timothy Spall, Emily Mortimer, Cherry Jones, Cillian Murphy and Bruno Ganz tussles for a lean 71 minutes. While too many plot details threaten to spoil a delicious denouement, here’s the gist: an eclectic mix of guests gather at Janet’s (Kristin Scott Thomas) elegant London home to toast to her new appointment as health minister, a seeming boon in an increasingly bleak political moment. But, by night’s end, their verbal sparring, accompanied by a slate of life-altering revelations (from adultery to a medical diagnosis), derails any hopes of a sit-down dinner. And then there’s that pesky Chekhovian gun…” (Olivia Aylmer, Vanity Fair)

Step (2017, dir. Amanda Lipitz) – Hulu

“Step looks like a dance film, but it’s really a rollercoaster ride about expectations, drive, and achievement. The weight in each rhythmic stomp produced by the young women featured in this movie isn’t just to produce a sound in glorious sync, but to signal a togetherness in an often-brutal world. Amanda Lipitz’s inspiring, Sundance award-winning documentary follows three African American teenage girls in Baltimore as they wend their way through a senior year in which they’re not just contenders for a statewide step dance crown, but also the first graduating class at an all-girls charter school designed with the express purpose of sending its students to college. The competition in Step isn’t just to hit a stage and win a talent prize, but to beat the odds in life. Start figuring out now how to clap and dab away tears at the same time; it’s that kind of experience.” (Robert Abele, TheWrap)

Shirkers (2018, dir. Sandi Tan) – Netflix

“Shirkers is a documentary about the production of an uncompleted movie, but it doubles as an upgraded version of the missing project itself. As a punk teen in early-nineties Singapore, Sandi Tan wrote a feminist slasher movie for the ages, an exploitation road movie designed to ruminate on the energy of youth, creativity, and alienation. The director, a much older American high school instructor with dubious motives, stole the film canisters for unknown reasons and vanished into the mist; two decades later, Tan has completed a fascinating personal look at her quest to uncover his motives, resurrecting the significance of her original intentions in the process.” (Eric Kohn, IndieWire)

To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before (2018, dir. Susan Johnson) – Netflix

“Romantic comedies have been forging a comeback, led by a recent boom on Netflix. The latest strong case for the genre’s revival is To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before, which embraces its rom-com trappings with a distinctly millennial self-awareness. Based on Jenny Han’s beloved YA novel by the same name, the movie centers on the life of Lara Jean Covey (X-Men: Apocalypse‘s Lana Condor), a shy high school student who’d rather watch Sixteen Candles on a Friday night than try to find her Jake Ryan in real life. Her widowed father (John Corbett) and protective sisters worry that she’ll spend the rest of high school with her nose buried in her treasured romance novels as opposed to socializing. That all changes when the secret love letters she has written to her crushes–who range from the jock she smooched during a game of Spin the Bottle in the seventh grade to the boy next door who also happens to be her big sister’s boyfriend–are mysteriously sent to their addresses. As might be expected, chaos ensues. But Lara Jean’s embarrassing predicament soon develops into an unlikely love triangle that encourages her to come out of her shell and embrace her vulnerability.

“In many ways, the story feels like the teenage rom-coms of years past that Lara Jean loves to watch–but its sensitivity and cultural consciousness improves on its predecessors. In one memorable sequence, Lara Jean (who’s biracial, Korean and white) watches Sixteen Candles on a date, leading to a thoughtful discussion of the film’s now-glaring racism. Other complex issues–like slut-shaming, cyberbullying and the death of a parent–are tackled with nuance. Equally refreshing is the care given in establishing Lara Jean as the heroine of her life. In a genre that frequently resorts to clichés, the movie resists reducing her to an adorkable, lovelorn lead. Much of this is thanks to Condor, who plays Lara Jean with a charming pluckiness that reads as both endearing and empowering.

“To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before is only one of a plethora of youthful rom-coms to hit Netflix this summer in the streaming giant’s bid to bring back the form. But its heartwarming and clear-eyed approach to first love and the challenges of coming-of-age distinguishes it from its contemporaries. Add it to your queue.” (Cady Lang, TIME Magazine)