As August came to a close, I eked out some time for a melodrama I had been curious about for years, A Summer Place. I’m not sure what I expected aside from repetitions of the love theme popularized by Percy Faith & His Orchestra, but I was surprisingly moved by the ways that the actors brought their characters to life in a story that, like its contemporaries Gidget (1959) and Where the Boys Are (1960), pushes the boundaries of how sex was discussed in mainstream Hollywood cinema.

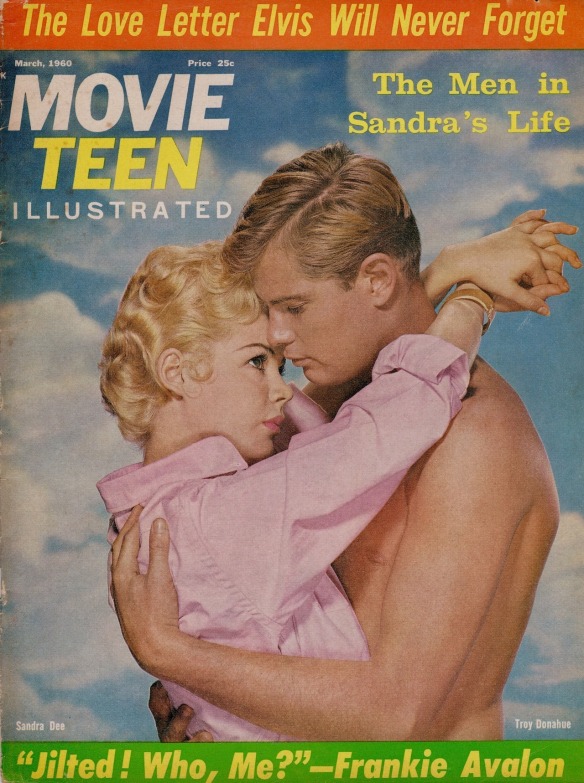

Filled with as many tangles as any tale of star-crossed lovers, A Summer Place focuses as much on societal/generational clashes as on the theme of second chances. It all starts when Bart Hunter (Arthur Kennedy), owner and proprietor of a somewhat run-down inn on an island off the coast of Maine, announces to his wife Sylvia (Dorothy McGuire) that their incoming guests for the summer will be a man they grew up with on the island, Ken Jorgenson (Richard Egan), along with his family. Although Sylvia has never told Bart, she and Ken were in love when they were young adults, before class distinctions drove them apart. Now, decades later, Ken is a self-made millionaire stuck in a passionless marriage to Helen (Constance Ford), who is preoccupied with their teenage daughter Molly’s (Sandra Dee) chastity. Upon reaching the inn, both families are immediately tested: Molly is charmed by Bart and Sylvia’s handsome, college-bound son Johnny (Troy Donahue), while Ken and Sylvia are drawn to one another as surely as if they were their kids’ ages once more.

Worry sets in for the older paramours as they watch their children, concerned that Molly and Johnny are doomed to repeat the same mistakes. This is where A Summer Place finds its footing as a romantic drama. Sandra Dee, whose performances in Imitation of Life (1959), the aforementioned Gidget and Portrait in Black (1960) had ranged from “just OK” to “good” in my estimation, does an absolutely fantastic job at articulating Molly’s conflicted emotions in Delmer Daves’ film. I’m not embarrassed to admit that I shed some tears. The same cannot be said of Troy Donahue, who plays Johnny with all the intensity of a block of wood, but at least he adequately conveys the character’s sweetness. In fairness, it’s refreshing to see a teen boy depicted as more sexually inexperienced and unsure of himself than a girl, although she’s hardly worldly; Molly’s history seems to be restricted to making out.

As was the case for the adolescent protagonists of another censorship-pushing 1959 film, Blue Denim, Molly and Johnny’s loss of virginity is followed up with frank conversations about pregnancy and abortion, some of which are beyond dated. But again, Sandra Dee handles Molly’s zigzagging between pursuing desire and bowing to social conventions – trying to combat the burdensome shame of not living up to the expectations of a “good” girl’s behavior – with mature poise. Equally worthy of praise is Constance Ford’s role as Molly’s obsessive mother, who demonizes her daughter with the cruelest tactics she can think of to break up the teen couple, including a first-time gynecological exam to determine whether Molly has had sex (she had not at that point). A Summer Place ultimately hews to Hollywood’s Hays Code edicts about sexuality and marriage, but its sympathetic view of Molly’s journey is as effective now as it must have been sixty years ago.

Furthermore, as a supplemental reading, Sandra Dee’s 1991 essay for People about surviving childhood sexual abuse and subsequently battling anorexia and drug/alcohol addictions (the latter two leading to her eventual death from kidney failure) gave me insight into how she was able to relate to the most serious aspects of what Molly Jorgenson endures. I can’t imagine how difficult it was for Dee – who was only sixteen when A Summer Place was shot – to balance her newfound stardom with her past and present traumas, but the fact that she could so expertly hide that pain (even though she obviously should not have had to) and become a candy-coated icon of teen fun is a testament to her inner strength and acting ability.