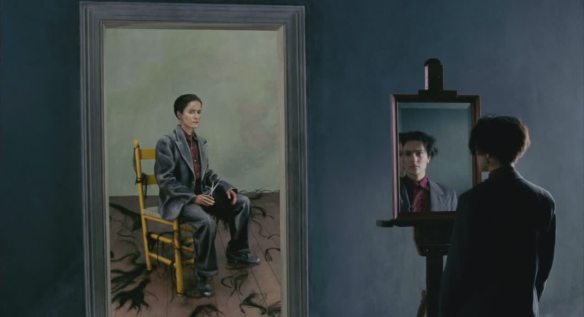

Actress Imogen Poots (l.) and director/screenwriter Sophia Takal (r.) on the set of Black Christmas, 2019. (Photo: Fortune Magazine via Kirsty Griffin/Universal Pictures)

Better late than never! Just as 2019 comes to a close: here are fourteen new movies due to be released in theaters or via other viewing platforms this December, all of which have been directed and/or photographed by women. These titles are sure to intrigue cinephiles and also provoke meaningful discussions on the film world, as well as the world in general.

DECEMBER 6 (in theaters), DECEMBER 10 (VOD): In Fabric (dir. Peter Strickland) (DP: Ari Wegner) – Metrograph synopsis: “A lonely woman (Marianne Jean-Baptiste), recently separated from her husband, visits a bewitching London department store in search of a dress that will transform her life. She’s fitted with a perfectly flattering, artery-red gown—which, in time, will come to unleash a malevolent curse and unstoppable evil, threatening everyone who comes into its path. From acclaimed horror director Peter Strickland, the singular auteur behind the sumptuous sadomasochistic romance The Duke of Burgundy and auditory giallo-homage Berberian Sound Studio, comes a truly nightmarish film, at turns frightening, seductive, and darkly humorous. Channeling voyeuristic fantasies of high fashion and bloodshed, In Fabric is Strickland’s most twisted and brilliantly original vision yet.”

DECEMBER 6 (in theaters & on VOD): Knives and Skin (dir. Jennifer Reeder) – IFC Films synopsis: “Knives and Skin follows the investigation of a young girl’s disappearance in a stylized version of a rural Midwest town that hovers just above reality, led by an inexperienced local sheriff. Unusual coping techniques develop among the traumatized small-town residents with each new secret revealed. The ripple of fear and suspicion destroys some relationships and strengthens others. The backdrop of trauma colors quintessential rituals—classrooms, dances, courtship, football games—in which the teenagers experience an accelerated loss of innocence while their parents are forced to confront adulthood failures. This mystical teen noir presents coming of age as a lifelong process and examines the profound impact of grief.”

DECEMBER 6 (in theaters & on VOD/digital): Little Joe (dir. Jessica Hausner) – Variety’s Cannes Film Festival review by Owen Gleiberman: “Just about every horror movie has an opening stretch — it could be 20 minutes, or even the first 45 — that inches along in a creep-out mode of anticipatory anxiety, building to the moment when the demon, the slasher, the monster, the source of the fear factor is revealed. These days, the film will then usually turn into a ride. But even if it doesn’t, the source of the horror always becomes tangible, visible, alive. It takes audacity, and a special skill, to sustain that early mood of premonitory dread over an entire film. And that’s what happens in Little Joe, an artfully unnerving, austerely hypnotic horror movie about a very sinister plant.

“Behind the opening credits, the camera hovers, at a skewed high angle, over rows and rows of flower seedlings — hundreds of them — arranged with antiseptic precision in some sort of glassed-in white-on-white tech bunker of a laboratory. It’s hard not to notice that the flowers look a bit phallic, and when viewed in closeup, the bulbs, with a bit of red poking out at the top, suggest Venus flytraps just after they’ve had a munch. Years of horror thrillers have geared us to survey a scene like this one and expect, down the road, the eruption of something ghastly: an alien, perhaps, or monster seed pods like the ones in Invasion of the Body Snatchers. Little Joe wants us to be quietly unsettled by those plants. We look at them and wonder: Is this a nursery from hell?

“The answer is yes, sort of. Little Joe, it turns out, is a variation on Invasion of the Body Snatchers. But it’s not the umpteenth remake; we hardly need another one of those. Instead, the Austrian filmmaker Jessica Hausner, directing her first English-language feature (and her fourth film to be shown at Cannes), picks up on the proverbial “Body Snatchers” theme — people turned into sinister conformist replicants of themselves — and updates it to our era in a singular and disturbing way.

“In Little Joe, Hausner works in a shivery and deliberate modernist spook-show style, one that calls up echoes of early David Cronenberg and the Stanley Kubrick of The Shining. She holds us in a refined trance, tantalized with fascination at what’s waiting around the corner. Keeping her camera moving with slow-glide voyeurism, she turns those plants into disquieting creatures even when they’re just sitting there being their innocent selves.

“The high-tech hothouse nursery where much the film is set is part of Planthouse Biotechnologies, a corporate plant-breeding laboratory in England that uses genetic engineering to create profitable new breeds. The seedlings glimpsed in the opening scene are the creation of Alice Woodard (Emily Beecham), a senior plant breeder with the company who has come up with the idea of a flower that gives off a scent so ambrosial it makes people euphoric just to sniff it. The flower she’s invented is pretty, but in a deceptively unspectacular way. It has a brown stem with a slight curve in it that looks like the sort of ‘designer’ lamp you can buy at Target, and the bud opens into a snowball of red tendrils that makes the flower resemble an exotic chrysanthemum. Alice takes one of the plants home, where she lives as a single mom with her son, Joe (Kit Connor), who looks to be about 12. Setting the plant on a table with a light over it, she even names it: She calls the flower — and the entire breed — Little Joe.

“The flower’s scent is indeed divine. People take in one smoky burst of that pollen (it happens when the plant spreads its tendrils), and it transforms their mood. They feel happy. But they also feel different. They no longer feel completely like themselves. They look and sound the same, but on some barely perceptible level they don’t act in quite the same way. They’re a bit placid, a bit neutral, a bit in their own zone. They’re no longer engaged — not really — with the outside world. But it doesn’t matter (at least, to them), because the new way they feel is just as good; in fact, it feels better. They want to keep feeling that way. And thanks to the effect of Little Joe, they do.

“If this all sounds vaguely familiar, that’s because Hausner, working from a script she co-wrote with Géraldine Bajard, has built Little Joe around a daring metaphor. The original Invasion of the Body Snatchers, made in 1956, with ordinary buttoned-down citizens being turned into emotionless ‘pod people,’ has sometimes been interpreted as a comment on the McCarthy era, but it was really a sci-fi allegory of the creeping social conformity of the 1950s. The 1978 version updated that same drone-of-conformity idea to the flaked-out weirdness of the post-counterculture ’70s.

“Little Joe spins it into a startling satirical view of the age of psychopharmacological drugs. The plants in Little Joe are nothing more, or less, than a horror-movie version of antidepressants. And in terms of the film’s drama, what’s sinister isn’t just the change in behavior we note in various characters: first Joe, a sweet kid who turns quietly indifferent to his mother, then Chris (Ben Whishaw), Alice’s devoted assistant on the plant project, who’s got a crush on her but then seems to morph into an office drone.

“No, the really creepy thing is the loyalty they develop to the plant that’s transformed them. Once they’ve been converted to their new state of weirdly numb contentment, they become fiercely protective of their new way of being; no one is allowed to question it. And that’s the scathing allegorical thrust of Little Joe. It presents a landscape of medicated zombies who join in a cult of their own well-being, and who regard their new state as an ideology — not just a way to be but the way to be. Symbolically speaking, they’re addicts who don’t know it, hooked on the sinister interior aroma of mood-modification drugs.

“Hausner gets pinpoint performances out of her actors, and she needs to, since so much of Little Joe pivots around the subtlest of personality shadings. Emily Beecham, who’s like a more vivacious Claire Foy, plays Alice as beaming but increasingly troubled, a scientist who didn’t know she created a monster, and is now desperate to put that genie back in the bottle. Ben Whishaw is super-sly as the benign colleague who becomes a weasel without quite shedding his devotion to Alice. He’s not against her; he just wants her to join. David Wilmot is an arresting chameleon — now raging, now snake-oil smooth — as Alice’s office mate Karl, and Kerry Fox is superb as Bella, the mentally fragile Planthouse veteran who’s the first one to detect a shift in personality (in her dog). As for the film’s musical score, by Teiji Ito and Markus Binder, it’s practically another character: an Asian-flavored cacophony of drip drums, flute quavers, and shrieking tech that goes to work on your system.

“How you react to Little Joe may well hinge on your own beliefs about antidepressants — whether you think they’re an unalloyed force of good, a profit-driven conspiracy by Big Pharma (with the psychiatric establishment as their marketer/enablers), or something in between. But given how little direct criticism of our psychotropic-drug culture you can actually encounter in the media, it may be that a horror movie — albeit a shiveringly delicate and understated art-house one — is the ideal way to present the argument that we’re becoming a society of people too artificially addicted to well-being, regardless of the cost, to see anything outside it.”

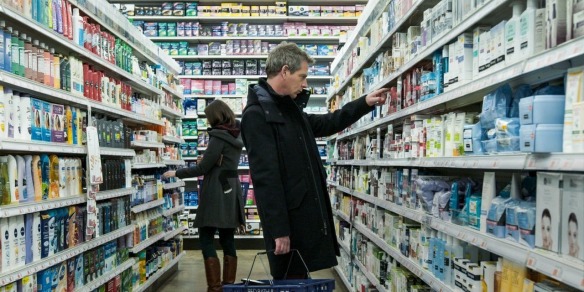

DECEMBER 6: A Million Little Pieces (dir. Sam Taylor-Johnson) – Chicago Sun-Times review by Richard Roeper: “You had to feel for James Frey. In January 2006, the School of the Art Institute grad turned best-selling author took arguably the most brutal verbal beatdown in the history of ‘The Oprah Winfrey Show.’ Granted, Frey brought it upon himself, when it was revealed his mega-successful addiction memoir A Million Little Pieces contained major exaggerations and fabrications. Oprah, who initially had championed the book, was not amused. She called Frey on the carpet in front of a studio audience and millions of viewers. It seemed excessive. It was painful to watch.

“A few years later, Oprah said she owed Frey an apology. By then, Frey had bounced back in a big way, with a seven-figure deal to write novels for Harper Collins. Since then, his career has continued to thrive, most recently with a ‘Story By’ credit for the acclaimed theatrical release Queen & Slim. Now, some 16 years after the publication of A Million Little Pieces, a film adaptation from director/co-writer Sam Taylor-Johnson (Fifty Shades of Grey, no relation) is getting an understated release, and it’s reasonable to assume a good percentage of viewers will have little or no knowledge of the controversial story behind the source material. Not that it should matter. As a stand-alone work of cinema fiction, A Million Little Pieces is an effective blunt instrument of a film — a rough-edged, unvarnished, painfully accurate portrayal of addiction and rehabilitation.

“Aaron Taylor-Johnson (husband of the director) delivers a stunning performance as the self-destructive, hardcore addict James. There’s nothing Hollywood or glamorous about this work; Taylor-Johnson looks like a walking ghost as James wakes up on a plane bound for Minneapolis (he doesn’t even know how he got there), where he is met by his brother Bob (Charlie Hunnam), who takes James straight to a rehab facility. Hunnam delivers steady, powerful work in a small but pivotal role. We all know someone like Bob (perhaps we’re someone like Bob), who is worn out by James’ behavior but refuses to give up on him, because he’s family.

“James is hardly all-in with a 12-step recovery plan; like many an addict, he thinks he’s smarter than everyone else in the room and he’ll figure out his own path to recovery. While in rehab, he meets archetypes such as a stern but caring supervisor (Dash Mihok, best known as Bunchy on ‘Ray Donovan’), a possible love interest in the badly broken Lilly (Odessa Young) and a father figure in a man named Leonard (Billy Bob Thornton). The fine supporting cast, most notably Thornton, rescue these roles from overly cliched status.

“Sam Taylor-Johnson infuses A Million Little Pieces with a frenetic, jarring style capturing the fragmented, jagged, blurred-realities world of the addict, and Aaron Taylor-Johnson delivers a raw, bruising, commanding performance as a man who is either going to find a measure of peace in the day-to-day world of recovery or is going to wind up dead. There’s no third option. But as James Frey has demonstrated, there IS such a thing as a second act in an American life.”

DECEMBER 6 (in select cities); FEBRUARY 14, 2020 (wide release): Portrait of a Lady on Fire (dir. Céline Sciamma) (DP: Claire Mathon) – Slate review by Dana Stevens: “Why, Héloïse wants to know, does the portrait look so little like its subject? ‘There are rules. Conventions. Ideas,’ explains Marianne, unconvincingly. The face in the painting, Marianne’s first attempt at a portrait of Héloïse, is placid, rosy, and conventionally feminine in its inoffensive prettiness; the real Héloïse (Adèle Haenel), though even more beautiful, has an intimidatingly direct gaze and a serious, even somber demeanor. But given the purpose of the portrait—Heloïse’s mother plans to present it as a gift to the Italian nobleman whom Héloïse is to marry, sight unseen—it’s understandable why Marianne (Noémie Merlant) would soften Héloïse’s features and blunt the severity of her expression. In Céline Sciamma’s austere yet sensuous fourth feature Portrait of a Lady on Fire (which opens Friday in New York and Los Angeles before a wide release in February), this frequently altered painting becomes an index of the changing relationship between the two young women: At first distant, proper and ladylike, it slowly turns into something passionate, truthful, and almost unbearably intimate.

“Of course, another reason the portrait might not resemble Héloïse at first is because she never posed for it. Furious at her powerlessness to escape the arranged marriage, she walked out midsitting on the last artist who tried to paint her, leading him to destroy his work. Now her mother (Valeria Golino) tells Héloïse that Marianne has been brought in to be her companion on her daily cliffside walks; Marianne must soak in as much about Héloïse as she can on those walks, squirrel away sketches, and work on the portrait in private. There’s more backstory, but the information needed for the film’s stark setup is simple to grasp: two women, a canvas on an easel, a secret, the sea.

“The year, according to the production notes, is 1770, but no on-screen legend or other temporal marker clues us in to that date other than the women’s corseted floor-length dresses. The location is equally indeterminate: an isolated house on a high cliff by the ocean. (The film was shot on location on the coast of Brittany.) In the early scenes especially, the story seems to take place in a timeless, almost abstract space, like the films Ingmar Bergman shot with only a handful of actors on the Swedish island of Fårö. Though men appear, namelessly and briefly, at the beginning and end, Portrait of a Lady on Fire takes place almost completely in a world made up of women: the two leads, Heloïse’s mother, the young house servant Sophie (Luàna Bajrami), and in one scene a group of village women who sing a haunting a cappella song around a bonfire. But it’s the off-screen men who call all the shots in these women’s lives; those rules, conventions, and ideas that govern Marianne’s painting of an upper-class bride-to-be are the same ones responsible for Héloïse’s desperate sense of entrapment.

“To give away any more than the fact that the two women fall madly in love would be to deprive the viewer of Portrait of a Lady on Fire’s greatest pleasures: the stolen glances on cliffside walks, the conversations that end just as the truth is about to be spoken, the quiet contests of will over the content and meaning of that ever-changing canvas. Again and again Sciamma finds ways to deliver meaning cinematically rather than in words, whether through the placement of faces in the frame or a detail revealed obliquely in a mirror. In addition to being a swoon-worthy romance—a bodice-ripper in which corsets are not torn but slowly, lovingly unlaced—this is a meditation on feminism, art, and feminist art, as embodied by the portrait of the title but also by the embroidery being stitched by Sophie the housemaid—and, late in the film, by an extraordinary artistic collaboration the three young women undertake together. Without ever needing to spell it out, Sciamma makes clear that the weight of patriarchy means that this idyll by the sea may be these young women’s one chance to experience anything like real passion or freedom. That knowledge, on both the audience’s part and the lovers’, lends every moment of their time together—a fragment of music Marianne plays for Héloïse on the harpsichord, a shared reading of Ovid’s Metamorphoses—a kind of desperate poignancy.

“Adèle Haenel, the fierce-eyed, dark-browed beauty who plays Héloïse, may be familiar to audiences from her roles as an uncompromising AIDS activist in the 2017 French drama BPM or a young Belgian doctor in the Dardenne brothers’ The Unknown Girl. She’s also Sciamma’s romantic partner in real life and has already played the object of desire in the director’s debut film, Water Lilies. That real-life connection, whether you go in knowing about it or not, adds another layer to what’s on screen: the story of one woman attempting to render her love for another, not only with a paintbrush but with a camera. As Marianne, Noémie Merlant is also extraordinary: As she stands at the easel her huge dark eyes take in every detail of her beloved’s face, and though she didn’t do the painting herself (the portraits in the film are by the artist Hélène Delmaire), you completely believe she could have.

“Portrait of a Lady on Fire is that rare movie in which every choice feels thought through, meaningful, and right, from the costumes by Dorothée Guiraud to the cinematography by Claire Mathon. (When it comes to collaborating on feminist art, Sciamma walks the walk.) When the musical passage Marianne plays for Héloïse early in the film—the ‘Summer’ section of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons—returns at the end in its full orchestral glory, there’s a sense of inevitable, if tragic, completeness. Just like the short time the lovers have together, Portrait of a Lady on Fire is minimal but perfect, without an image, a glance, or a brushstroke to spare.”

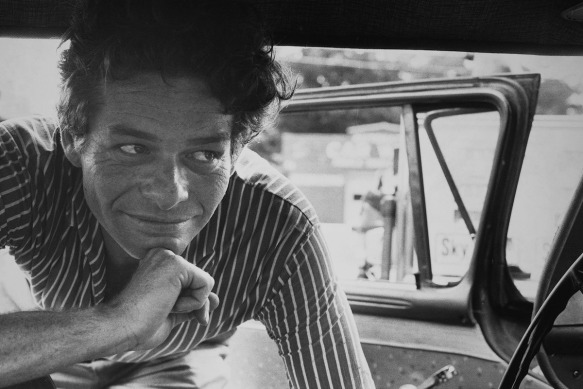

DECEMBER 13: Black Christmas (dir. Sophia Takal) – Los Angeles Times review by Kimber Myers: “The biggest gross-out moment in Black Christmas isn’t the gory death of a sorority girl at the gloved hands of a masked killer. Instead, it’s the scene where a cop globs mayonnaise onto white bread. This PG-13 remake of Bob Clark’s 1974 slasher classic follows in the feminist footsteps of its predecessor, while still subverting audience expectations at each opportunity. Fans of the original — and those who like their horror movies deadly serious and brimming with blood — might not love writer-director Sophia Takal’s take, but Black Christmas is a fun film that gets its kicks out of literally smashing the patriarchy.

“Structural misogyny is alive and well on the Hawthorne College campus, whether in the form of white-male-author-loving professor Gelson (Cary Elwes) or the fraternities like Delta Kappa Omega where sexual assault is brushed under the beer-stained rugs. But Riley (Imogen Poots) and her sorority sisters at Mu Kappa Epsilon are fighting back, and their efforts have made them targets of a killer who is stalking the quad as campus quiets for the holidays. Sorority girls — ahem, women — begin disappearing, while Riley is getting creepy DMs from someone claiming to be Hawthorne’s long-dead founder who seems to have chosen her as his next victim.

“While Takal’s previous work — her stunning debut Always Shine and the solid ‘New Year, New You’ episode of Hulu’s ‘Into the Dark’ — focused on the pain women inflict on one another as a result of society’s pressures, Black Christmas is more concerned with men as its villains. Clark’s film wore its second-wave feminism on its ’70s-era blouse sleeves, so it shouldn’t be surprising that Takal’s Black Christmas is a women’s horror film for a new generation, full of cheeky pro-female T-shirts and casual talk about menstrual cups.

“But this version doesn’t just update the disturbing phone calls of the original for menacing DMs; it gives the sorority sisters the agency to fight back in ways Clark’s movie didn’t. The script from Takal and April Wolfe isn’t subtle in its message about the dangers of toxic masculinity and rape culture versus the power of female solidarity, but it also has fun with its feminist themes in ways that will have like-minded viewers cheering and the less-enlightened shaking their fists. While the commentary is pointed, their screenplay is often blunt, hammering home the film’s larger ideas. Beyond Riley, the sorority sisters feel largely interchangeable, and more characterization could have helped invest the audience more deeply in their safety and survival.

“The PG-13 rating for Black Christmas might seem like a ploy for a larger, younger audience, but the lack of explicit violence feels more like a deliberate choice for Takal. The genre often glories in the gory deaths of women, but Black Christmas cuts away from the kill shot.

“This doesn’t always work — sacrificing visual coherence and sometimes leaving the audience wondering exactly what just happened — but it subverts the usual visual pleasures and terrors of horror films in a manner aligned with its larger themes. This remains a horror film, but it’s a sometimes enjoyably goofy one that prefers to make its audience laugh than to make them scream.”

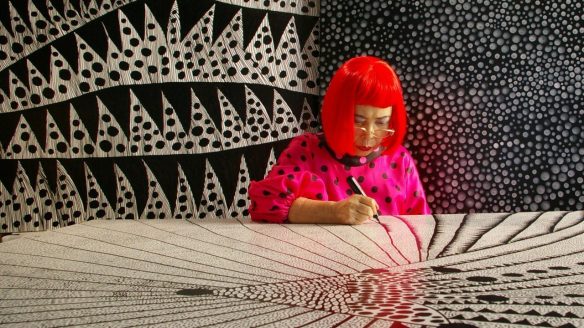

DECEMBER 13: Cunningham (dir. Alla Kovgan) – Film at Lincoln Center synopsis: “One of the most visionary choreographers of the 20th century, Merce Cunningham could also be counted among its great modern artists, part of a coterie of important experimenters across media that included Robert Rauschenberg, Brian Eno, Jasper Johns, and his long-term romantic partner John Cage. This painstakingly constructed new documentary both charts his artistic evolution over the course of three decades and immerses the viewer in the precise rhythms and dynamic movements of his choreography through a 3D process that allows us to step inside the dance. Director Alla Kovgan has created a visceral experience that both reimagines and pays tribute to Cunningham’s groundbreaking technique.”

DECEMBER 13 (in theaters & on digital/VOD): Rabid (dirs. Jen Soska and Sylvia Soska) (DP: Kim Derko) – Eye for Film’s FrightFest review by Jennie Kermode: “Remaking an iconic film is always a difficult proposition. Whatever you do, someone’s going to be unhappy, and even if it’s widely agreed that you’ve done a good job, you’ll only get limited credit for your work. For this reason, some filmmakers refuse to have anything to do with it – but where there is a fresh artistic angle to explore, the stakes change. The Soska sisters’ Rabid is less a remake and more of a reconstruction of the story in David Cronenberg’s original Rabid, approaching it with different priorities.

“Groundbreaking as it was, Cronenberg’s film had a plot that mirrored this, the traffic accident that precipitates the action (and foreshadows one of the director’s own experiments with somebody else’s material, Crash) coming out of nowhere. Here, we get the sense that Rose has been crashing all her life. Played this time around by Laura Vandervoort, she’s no longer a model but a fashion designer, an early hint that she will have more agency – but just as the Soska sisters acknowledge the advances that women have made, they introduce us to her as a bruised and uncertain young woman in a mercenary industry where ego is essential to survival. Because we get to know her before the crash, we understand it as something with more than superficial consequences. Rose’s facial disfigurement doesn’t just rob her of her beauty, it fractures her sense of identity.

“The solution to this is a trip to a private clinic working with experimental skin grafts. Rose isn’t rich – that myth about the fashion industry is knocked firmly on the head – but she is assured that, because she is such a perfect subject, all the costs will be met for in return for her ongoing availability for follow-up study. When after the procedure, her doctor takes her aside for a word about side effects, some viewers will experience flashbacks to Meryl Streep in Death Becomes Her: “Now a warning?!” But this film is nothing if not self-aware. It’s peppered with references to Cronenberg’s own work and much more besides. Indeed, it opens with a conversation about the dubious value of originality in art. Self-consciousness is an important aspect of the subject under dissection. Like Gene Tierney’s Laura or Clint Eastwood’s Man With No Name, Rose has the qualities of an archetypal, folkloric figure, enduring the same events over and over again in different places, in different forms.

“Whilst there is nothing here that awes quite like Cronenberg’s metro panic scene, with what we see of events playing out on a smaller scale to suit a still-tight budget and tighter on-set health and safety regulations, the new Rabid still delivers its share of shocks, this time in an atmosphere charged by reflections on the #MeToo movement and the way that violence functions as an everyday factor in many women’s lives. It’s lit in a style that plays with the clichés of fashion studio shoots, the huge empty apartment in which Rose stays with her foster sister Chelsea (Hanneke Talbot) taking on the qualities of a stage. Like the slick medical packaging around the ‘protein blend’ that our heroine is given to quench strange appetites, it has a distancing effect. In fashion, says Rose, you can be anything you want to be, but in accepting a new version of her old face she puts herself in a position where other identities are grafted onto her. Making one small concession after another, she gradually cedes her humanity, the physical changes that follow coming to seem entirely logical.

“Lingering on the sidelines, Chelsea is a witness unable to change events, with all the emotional baggage that brings. Moving closer as the narrative evolves is fashion photographer Brad (Benjamin Hollingsworth), whose persistent interest in Rose disquiets her despite her initial attraction to him, as if concession to that would inevitably entail a loss of power. Meanwhile, the shapes and coded guises of the fashion world move in and out of focus, abstraction passing comment on itself. Though some viewers seems to have missed it entirely, there’s a lot of humour here. It’s necessary for the film to retain its balance and remain engaging.

“It’s existential horror that really makes Rabid work and if this version has one major flaw it’s that it focuses too much on the physical towards the end, with aspects of the final sequence resembling certain video games and consequently losing their impact. For the most part, however, this is an impressive film, building on the original but speaking for itself. At a time when social norms are undergoing rapid shifts, it nevertheless succeeds in establishing a sense of otherness, in finding the edge.”

DECEMBER 13: Seberg (dir. Benedict Andrews) (DP: Rachel Morrison) – Time Magazine’s Venice Film Festival review by Stephanie Zacharek: “Once you’ve seen Jean Seberg’s face, a marvel of secrecy and revelation akin to the shifting tones of leaves in afternoon light, you never forget it. Seberg is probably best known as the co-star of Jean-Luc Godard’s 1960 Breathless, a film that helped introduce the then-newborn French New Wave to the world. She plays the femme fatale Patricia Franchini, an American in Paris aspiring to be a journalist. Her handsome petty-criminal boyfriend, played by Jean-Paul Belmondo, murders a policeman and retreats to Patricia’s apartment to hide, but in the end, rather than protecting him, she brings about his downfall. As Patricia, Seberg’s face is a charming but not fully readable mask of youthful self-assurance and ambition, half sweet, half cool, and framed by a sunray-colored pixie cut. She’s a gamine with a scheme, loyal to herself above all others.

“Kristen Stewart, her features so unmistakable and definitive, is all wrong to play Seberg—but only until you’ve watched her for, say, 10 minutes, or maybe 15, after which she and the mysterious, beguiling, ill-fated actress appear to meld into one bold, shimmering presence. This Stewart-Seberg human hologram is the center of British stage director Benedict Andrews’ Seberg, playing here in Venice out of competition. Seberg isn’t strictly a biopic; it’s a blunt portrait of a woman, a political activist as well as a movie star, whose life was kicked into a downward spiral by a devious government organization. The picture is potent and engaging; even its fictionalized elements ring with the spirit of truth. And Stewart is off the charts, though that’s hardly a surprise. She’s among the greatest actresses of our day, though to call her ‘great’ does a disservice to her subtlety—maybe it’s better to call her the master of the small gesture. The flicker of her eyelids is a dialect unto itself.

“Seberg focuses on one period in the actress’ life, the late 1960s and early 1970s, during which she was the subject—and the victim—of an investigation launched by the FBI’s COINTELPRO program under the guidance of J. Edgar Hoover. Seberg, who was born in Iowa but made her name chiefly in European films, was by all accounts a thoughtful actor and human being, but her life wasn’t a happy one, and Andrews’ film offers some highly believable explanations for that. She attracted the FBI’s attention because she’d given money to several Civil Rights groups in the 1960s, as well as to the Black Panther Party. She was also involved in a brief extramarital affair with activist Hakim Abdullah Jamal (played here, with perfectly modulated expressiveness, by Anthony Mackie).

“Beginning in the late 1960s, after Seberg had come to Hollywood to make a film (the 1969 musical Paint Your Wagon), the FBI harassed, intimidated and spied on her, prying into her personal life and spreading damaging rumors. In Seberg, the two FBI agents assigned to the case are played by Vince Vaughn and Jack O’Connell: It’s O’Connell’s character, Jack Solomon, who comes to feel sympathy for the duo’s target, seeing that she’s being needlessly crushed in the gears of Hoover’s plan to eradicate black activist groups. O’Connell brings some deeply human shading to his characterization of this by-the-book government guy. In one of the movie’s finest scenes—presumably a fantasy, a small, glittering thread of wishful thinking—Solomon approaches Seberg in a Parisian bar, circa the early 1970s, presenting her with her FBI file. She looks at it with anger, with curiosity—and then she passes it back to him. This is the movie’s way of granting Seberg some of the dignity she was denied in real life. In the movie, if not in life, she knows the extent of what was done to her; she couldn’t have known the scope of it as she was living through it, and suffering.

“In 1970, when the bureau learned that Seberg was four months pregnant, they spread rumors that a leader of the Black Panther party had fathered the child. (In the film, Jamal is cited as the alleged father.) The rumors damaged not only Seberg’s professional reputation, but her personal life. She attempted suicide several times, and in 1979 was found dead in her car, not far from her Paris apartment. Her death was ruled a probable suicide. Her ex-husband, the writer Romain Gary, blamed the FBI for her death, claiming that the agency’s investigations caused permanent and escalating emotional damage.

“Seberg doesn’t depict that end—the circumstances of the actress’ death are noted on a title card at the film’s close. That’s important, because Stewart plays Seberg as a woman full of life—she’s keeping Jean alive for us for the moments we’re able to watch her on-screen, and that time is precious. Stewart isn’t an impersonator or a mimic, which is why, in the early moments of Seberg, I found her a little wrong. Even with her perfectly bleached hair, and even though she’d perfected that elusive Sebergian half-pout, I looked at her and could see only Stewart, bold and brave in her stammering way. A little later, I saw how wrong I was. As an actor, Stewart is a vessel, not the driver of a vehicle. She didn’t ‘learn’ Seberg; she opened herself up to this sad, lost woman, allowing her to rush in, to fill every channel and vein. Stewart hears the language of ghosts, and she translates it for us. The words are all there, finding their way out through the light in her eyes.”

DECEMBER 20: Invisible Life (dir. Karim Aïnouz) (DP: Hélène Louvart) – Film Forum synopsis: “Acclaimed Brazilian filmmaker Karim Aïnouz brilliantly recreates 1950s Rio de Janeiro in this tropical melodrama of two inseparable sisters: Eurídice (Carol Duarte), 18, and Guida (Julia Stockler), 20. They live restricted lives with their conservative parents. However, each nourishes a passionate dream: Eurídice of becoming a renowned pianist; Guida of finding true love. In a shocking turn of events, they are separated and forced to live apart. Karim Aïnouz’s first film, Madame Satã, a Jean Genet-inspired story of 1930’s Rio’s drag demi-monde, premiered at Film Forum in 2003. Invisible Life shares with it this director’s commitment to immersing himself in the emotional lives of his characters, visualized through rich, inventive, and lush imagery. Based on Martha Batalha’s popular novel The Invisible Life of Eurídice Gusmão, the film is Brazil’s official submission to the 2020 Academy Awards® for Best International Film.”

DECEMBER 25: Little Women (dir. Greta Gerwig) – Polygon review by Karen Han: “In Greta Gerwig’s new film adaptation of Little Women, as the strong-willed Jo March (Saoirse Ronan) embarks on her writing career, her publisher (Tracy Letts) gives her some advice. If her main character is a woman, the story should end with her married or dead. The character must fall into a specific definition of womanhood, made more palatable for public consumption. Though Jo is living in the 1860s, similar rules still exist for female characters in popular culture today — hence the paper-thin female-led reboots of originally male-led movies, and facile ideas of what makes a female character strong. What makes Little Women particularly refreshing is that Gerwig treats the four March sisters as equals, rather than as right or wrong for wanting different things.

“Eldest sibling Meg (Emma Watson) is the domestic; among her sisters, she’s the best at taking care of the household. Unlike Jo, she wants to get married and have a family of her own. Jo is the most free-spirited sister, tomboyish and determined to have as much agency over her life as any man would have over his. Beth (Eliza Scanlen) is the shy one whose passion lies in music, rather than in an attempt to fly the coop like her sisters. Youngest sister Amy (Florence Pugh) is arguably Jo’s opposite, embracing stereotypically feminine ideas of beauty and propriety. She’s haughty where Jo is hot-tempered.

“The film, based on Louisa May Alcott’s 1868 novel, skips back and forth through time rather than unfolding chronologically. The sisters’ adolescence and young adulthood are shown in parallel, with Gerwig and editor Nick Houy making the transition between the two easily distinguishable by subtle shifts in color palette (the past generally uses warmer colors) as well as through characters’ hairstyles. As children, they’re bonded partially by necessity. They’re helping their mother (Laura Dern) make ends meet as their father (Bob Odenkirk) serves as a pastor in the Civil War. As young women, they’ve scattered, and they’re reckoning with where their desires in life have brought them, and with the expectations placed on women at the time.

“Gerwig gives each sister her fair shake. As the siblings grow into and through their teenage years, their disparate personalities and desires bring them into conflict, but Gerwig never allows any one March sister to come across as a villain. Their relationships with each other (and their lives in general) aren’t so black and white, and none of them are treated as foolish or lesser for what they want, even though they all want very different things. Even heartthrob Laurie (Timothée Chalamet), a force of chaos who captures both Jo’s and Amy’s attention, can’t tip the scales too far.

“That nuance is clearest in the dynamic between Jo and Amy, who lash out at each other, accusing each other of wrong or shallow choices. But Gerwig casts no such judgment on either of them. They’re both making the best of the patriarchal society they live in, with Amy understanding that she’ll marry for financial stability rather than love, and that her talent for art isn’t enough to grant her independence as a woman. And Jo submits to her publisher’s revisions to her short stories and novels because she knows there’s no other way they will get published, and earning money to help support her family is more important than her artistic integrity.

“Though most of Gerwig’s attention is on Jo, the evenhandedness with which she treats the whole family makes Little Women less a story about pursuing your dreams at any cost, and more about the value of kindness. One of the most affecting parts of the film is the burgeoning friendship between Beth and Mr. Laurence (Chris Cooper), an older gentleman who lives nearby. There’s little dialogue between them — they communicate largely through gestures. Beth is grateful for being able to come play the piano in his home, while he appreciates the simple comfort of her music. At the beginning of the film, it’s assumed that he’s a grouch and a recluse, but Beth’s kindness toward him reveals kindness in return.

“That may seem like a saccharine message, but Gerwig keeps the story in motion to the point where it’s difficult not to simply be swept up. The camera moves along with Jo as she rushes from one thought to the next, not only conveying a sense of her character, but a feeling of movement, growth, and freedom. The rush of youthful energy makes the film all the more affecting when it slows down, painting a comprehensive picture of the ups and downs of life rather than settling for something rose-colored.

“All their lives have meaning and importance, even if conventional pop culture wisdom or society might say otherwise. Meg isn’t lesser for wanting to get married, nor is Amy for being more stereotypically feminine, nor is Jo for being more stereotypically masculine in dress and behavior. As in Lady Bird, Gerwig allows her characters to be unconventional and selfish — that is, everything the stereotypical heroine isn’t supposed to be. It feels empowering to see four distinct women who all fall into different molds being treated respectfully, as though their decisions and personalities are all valid.

“Apart from one scene that feels like a belated, unnecessary recognition of the lack of racial diversity in the cast, the film doesn’t strike a single false note. It carries viewers through the lives of four very different women without picking any one to be the ‘right’ way of doing things. The cast is uniformly wonderful as well, with Pugh in particular perfectly embodying the way fits of youthful pique can get the better of us when we are denied the things we want. That degree of earnestness — and love for both the joyful and bittersweet parts of life — makes Little Women a pure joy.”

DECEMBER 26 (streaming on Netflix): The App (dir. Elisa Fuksas) – PopSugar synopsis: “In this ‘Black Mirror’-esque thriller, an actor and industrial heir heads to Rome to shoot his very first movie, but while he’s there, he starts using a dating app, and that habit gradually develops into a self-destructive obsession.”

DECEMBER 27: Clemency (dir. Chinonye Chukwu) – IndieWire’s Sundance Film Festival review by Eric Kohn: “At a time when movies can be reverse engineered to generate awards season buzz, Clemency provides a welcome alternative: a mature star-driven vehicle elevated by a brilliant performance that deserves all the awards it can get. As icy prison warden Bernadine Williams, Alfre Woodard embodies the extraordinary challenges of a woman tasked with sending men to their death, while bottling up her emotions so tight she looks as if she might blow. Writer-director Chinonye Chukwu’s second feature maintains the quiet, steady rhythms of a woman so consumed by her routine that by the end of the opening credits, it appears to have consumed her humanity as well. But over the course of the devastating process of preparing for another execution, Woodard injects the drama with the tantalizing possibility that humanity might creep back in.

“No matter the strength that Woodard brings to her role, Clemency is a tough sell from its harrowing opening minutes, in which Bernadine oversees the twelfth execution of her long tenure and witnesses it go horribly awry in front of a petrified crowd: Blood spurts, the body contorts, and Bernadine’s staff is traumatized. Chukwu captures the setup for this shocking accident in disturbing clinical terms, establishing a mood of the haunting psychological portrait to come.

“Bernadine was already a cold, humorless overlord, but the backlash to the execution only makes matters worse for the next victim in line. Anthony Woods (a restrained Aldis Hodge) retains his innocence for a homicide charge from years ago, and as the deadline for his execution looms, his frumpy, aging lawyer Marty (Richard Schiff, purposeful and wise) has started to lose his sense of commitment. In a series of tense exchanges with Bernadine, he rails against her lack of empathy for the prisoners even as he acknowledges the lost cause at hand. ‘You can’t save the world,’ she sighs. ‘That’s the problem,’ he replies.

“In Bernadine’s view, she has a responsibility to treat the death sentence in professional terms, but that philosophy is at odds with the job at hand. In a pivotal scene, she describes the mechanical details of Anthony’s planned execution while he cries in silence, and the disconnect establishes the extent to which Bernadine has learned to obscure her sympathies to a near-psychotic degree.

“All of which means she’s not exactly well suited to be a supporting wife to her frustrated husband (Wendell Pierce, in a calm, measured turn). Clemency stumbles into more conventional melodramatic plotting as it chronicles Bernadine’s troubled marriage, but the actors never overplay their arguments, and their troubles certainly make sense in the context of Bernadine’s mounting pressures at work. As media attention grows and protestors gather outside the prison, it’s inevitable that she’ll reach some kind of breaking point — but even she lacks the power to save Anthony from the likelihood that he’ll die soon enough.

“It can be a suffocating experience to sit with such downbeat circumstances for nearly two hours, and Clemency does push the limit. Even Chukwu’s insightful screenplay can’t justify a tangential conversation between Bernadine and the aging chaplain (Michael O’Neill), or the handful of redundant conversations as the movie creeps toward its final act. But that bumpy middle section gives way to the mortifying suspense of the climactic moments, as the clock ticks down to Anthony’s execution and the likelihood of a magical reprieve continues to fade.

“Meanwhile, the movie leaves room to explore Anthony’s own struggles, as he veers from utter despair to tentative optimism and back again. In a fleeting scene as Anthony’s estranged partner, Danielle Brooks delivers a devastating monologue that puts Anthony’s past in context, as well as the movie’s themes. While Clemency doesn’t overstate the role of race in its scenario, it inevitably becomes a subtle thematic foundation as Bernadine contemplates her role in Anthony’s imminent death. As with Ava DuVernay’s Middle of Nowhere, Chukwu’s movie bemoans the endless of cycle of broken families caused by a system that puts black men behind bars on autopilot.

“Beyond that, Clemency illustrates how systematic execution can destroy both ends of the equation. Woodard portrays Bernadine as a shell of a woman a few shades shy of robot. Going out for drinks with one of her peers, he says, ‘You suck at conversation!’ Throughout Clemency, it’s clear that Bernadine has lost touch with the essence of human connection because her job so often requires her to end it.

“Chukwu maintains an impressive command over her material, but Woodard herself becomes the movie’s central storyteller. The final shot is a galvanizing snapshot of her internal battle, and possibility that it might finally make its way to the surface. While the title of Clemency may refer to the literal prospects of escaping death row, it’s equally invested in a personal quest for the exoneration of the soul.”

DECEMBER 27 (airing on Showtime at 9:00 PM EST): Duran Duran: There’s Something You Should Know (dir. Zoë Dobson) – Showtime synopsis: “With exclusive access, the band opens up about their extraordinary career and talks candidly about the highs and lows they have endured together over four long decades. This is the band at their most relaxed, intimate and honest. We spend time with John at his LA home; Simon pays a visit to his former choirmaster; Roger goes back to where it all started in Birmingham and Nick dusts off some of the 10,000 fashion items that the band have meticulously cataloged and collected over the course of their career.”