Director Marielle Heller (center) with actresses Dolly Wells and Melissa McCarthy on the set of Can You Ever Forgive Me?, 2017. (Photo: Town & Country)

Here are twenty-six new movies due to be released in theaters or via other viewing platforms this October, all of which have been directed and/or photographed by women. These titles are sure to intrigue cinephiles and also provoke meaningful discussions on the film world, as well as the world in general.

OCTOBER 3: Moynihan (dirs. Joseph Dorman and Toby Perl Freilich) – Film Forum synopsis: “‘Everyone is entitled to his own opinion – but not to his own facts.’ – Daniel Patrick Moynihan (1927-2003). His aristocratic demeanor and Harvard polish belied Moynihan’s Depression-era roots in NYC’s Hell’s Kitchen, the son of a single mother. Joseph Dorman (his documentary, Arguing the World, which we opened in 1998, is a thrilling account of the 60-year battle among New York’s 20th century intellectuals), with co-filmmaker Toby Perl Freilich (Inventing Our Life: The Kibbutz Experiment), now give us a portrait of a complex man who struggled to alleviate poverty and racism, but who was maligned for his use of the expression ‘benign neglect.’ Ta-Nehisi Coates, Eleanor Holmes Norton, George Will, and Henry Kissinger give insight into this “connoisseur of statistics” who served four presidents, anticipated the breakup of the Soviet Union, and was as comfortable writing about philosophy, ethnicity, and architecture as he was rethinking the Social Security and welfare systems.”

OCTOBER 5 (in theaters & streaming on Netflix): Private Life (dir. Tamara Jenkins) – RogerEbert.com review by Matt Zoller Seitz: “Sometimes you want something so badly that you chase it for years, and the quest takes over everything.

“That’s what happened to Rachel (Kathryn Hahn) and Richard (Paul Giamatti), the protagonists of Private Life, a comedy-drama about a forty-something New York couple who are desperate to become parents.

“Rachel is 41. She’s not as fertile as she used to be. Richard is 47. He has just one testicle, and it happens to be blocked. This is a terrible state of affairs for any couple, but a comic gold mine for actors who express frustration as brilliantly as these two. We sense early on that Rachel and Richard’s obsession distracts them from dealing with longstanding issues in their marriage, and maybe individual neuroses as well. Richard was once an acclaimed actor and theater impresario. He now runs a pickle-making company. Rachel is a writer who’s trying to finish a new novel. She’s finding it hard to stay focused with all the obstetrical drama going on. They know having a child is a long shot. They’ve tried various procedures and treatments and flirted with adoption and surrogates. They refuse to give up. Should they?

“The first part of Private Life follows Rachel and Richard through the medical system, undergoing tests to figure out if they have a specific problem that can be fixed by science. Their fertility sherpa, Dr. Dordick (Denis O’Hare), speaks frankly of the obstacles in their path. They hear him but don’t absorb the facts as deeply as they should—or maybe they’re just hopeless optimists. Richard and Rachel are close with their in-laws—Richard’s brother Charlie (John Carroll Lynch), his second wife Cynthia (Molly Shannon), and Cynthia’s college-age daughter Sadie (Kalyi Carter)—and lean on them for emotional support and sometimes more. There’s a bit of drama early on when Richard asks Charlie for a loan to pay for a medical test. Cynthia explodes, warning him that they’ve been at this forever and that he needs to stop enabling them.

“The movie shifts into a different mode—less raucously funny, more tenderly observant—when Sadie, a budding fiction writer herself, moves in with Richard and Rachel, and the couple asks if she’d donate her eggs. (The movie makes sure to spell out that none of them are related—Charlie being Richard’s stepbrother and Cynthia’s second husband.) Sadie is intrigued. She needs the money. She loves Richard and Rachel. And she’s at her own crossroads in life, and maybe feeling it’s time for a gesture as dramatic as anything in the short stories that she loves (or in fiction written by classmates that she gripes about—mostly ‘thinly veiled autobiographical crap about their upbringing;’ Sadie is oblivious to the fact that she’s living some of the same cliches she despises in the fiction and the lives of others).

“I don’t want to go into too much detail about the bulk of the story because the plot takes a lot of twists and turns, some predictable, others unexpected, and because what’s important are the observations, visual as well as verbal, embedded in each scene. The film’s writer-director, Tamara Jenkins (Slums of Beverly Hills, Savages) is a brilliant chronicler of upper-middle class white people and their foibles, and her eye for detail is anthropologically exact, empathetic but never begging for sympathy. She’s aware that these people can be myopic and petty, and that they’re so wrapped up in their individual dramas that they fail to appreciate what they do have; but she also understands the deep biological urges that drive Richard and Rachel, who spent the first part of adulthood committing to an artist’s life without taking on responsibility to anyone but each other.

“Some of Jenkins’ humor pushes right to the edge of farce without tipping over, as when Richard justifiably blows up at a doctor’s unprofessional behavior, then realizes he’s overdoing it and making a spectacle of himself. (Nobody does righteous snits better than Giamatti.) Other times, the film digs into the minutia of marriage and family life with the surgical precision of Mike Leigh, capturing fleeting images and moments that sum up an experience. The personalty test that Sadie takes in order to be cleared as a surrogate includes statements which, viewed in tight close-up, seem nearly poetic in their strangeness (‘Evil spirits possess me at times.’ ‘I would like to become a singer.’). A quick iris-to-black as Rachel succumbs to anesthesia, followed by a blurry shot from her point-of-view as she wakes up and sees a package of animal crackers and a bottle of apple juice on a meal tray, sum up the dreamlike feeling of suspension that accrues when you spend a lot of time in doctor’s offices, hospitals, and operating rooms, with their blank walls and identically uniformed employees. (Hahn, who’s on a roll these days, is at the top of her game, handling Jenkins’ barbed dialogue and the story’s many reactive closeups with equal skill.)

“The dialogue, especially between Rachel and Richard, is just as astute. We see what drew them together (a shared love of creativity plus undeniable comic chemistry) as well as the despair that they hide from each other for fear of making a tense partnership unpleasant. Each sometimes feels that their failure to conceive is the other’s fault, and Jenkins weaves social messaging into their reasons for waiting, acknowledging it as a factor without telling us if she thinks they made good or bad decisions. Richard stings Rachel by suggesting that she’s assigning blame for their situation onto the mixed messages she received about family and career back in college. ‘You can’t blame second wave feminism for our ambivalence about having a kid!’ he groans. To the film’s credit, neither is portrayed as being entirely wrong.

“The movie also succeeds as a portrait of a particular urban lifestyle—creative people living beyond their means because they don’t want to give up youthful dreams of the big city—as well as the larger forces that conspire to make their existence precarious and unrealistic. The Lower East Side New York neighborhood where Rachel and Richard have lived for decades has become almost entirely gentrified (except for their block, which Sadie says is ‘very Serpico‘). The site of Richard’s old theater company is a bank branch. Condos are springing up everywhere, promising a tourist-like experience of a city that no longer exists.

“But of course, Richard and Rachel were probably in the first wave of bourgeois settlers back in the ’90s, and as such, they have to accept some blame for how things have changed. When Sadie, out for a walk with her possible future egg donors, spots a billboard advertising luxury apartments with the slogan ‘Live in Luxury, Party Like a Punk,’ she snarls, ‘It’s like an open invitation for assholes.’ The movie is aware that they’re also the assholes. When they visit Richard’s brother and her family in the suburbs, they’re seeing a likely future. If they leave the city, does it mean they surrendered? If they don’t conceive, does it mean all of that time and money was wasted?

“It’s becoming increasingly hard for films like this to have a big impact on audiences, in part because stories about recognizable, present-day adults of every social class have been largely driven from theaters and onto TV and streaming platforms. Anything that doesn’t involve special effects and some kind of world-ending threat is deemed ‘low stakes’ or ‘television’ and thus not worth leaving home to see. (This one is getting a hybrid release from Netflix, playing a small number of theaters while debuting online.) But when the story is told in as engaging and fair-minded a way as it is here by Jenkins—who’s as adept with lyrical images as she is with snappy dialogue, and allows us to laugh at the characters even as we feel for them—it’s as immersive as any blockbuster, sneakily so. This film is a reminder that the smallness of life can feel huge when we’re in the middle of it. A perfect final shot sums up everything Private Life has been telling us and showing us, while letting us imagine Rachel and Richard’s destiny for ourselves.”

OCTOBER 5: Trouble (dir. Theresa Rebeck) (DP: Christina Voros) – City Cinemas Village East Cinema synopsis: “Trouble is a rollicking comedy about two siblings who stop at nothing to outwit one another. That fact that the dueling brother and sister in this case are middle- aged, but still feel a rivalry that most adults have long outgrown, makes theirs a particularly high-stakes conflict. Academy Award-winner Anjelica Huston stars as Maggie, a tough-as-nails widow who fights to hold onto the beautiful wooded farm in rural Vermont where she was raised and still lives, while Bill Pullman plays her ne’er-do-well brother, Ben, who plots to sell the land to developers right out from under Maggie. The film was written and directed by noted playwright and author Theresa Rebeck.”

OCTOBER 12 (in theaters & on VOD): After Everything (dirs. Hannah Marks and Joey Power) (DP: Sandra Valde-Hansen) – The Hollywood Reporter review by Frank Scheck: “Depicting the highs and lows of a relationship marked by a possibly terminal cancer diagnosis, Hannah Marks and Joey Power’s romantic drama somehow manages to avoid clichés and oversentimentality. After Everything deals with two 23-year-olds, but it will likely ring true even for viewers whose twenties are a distant memory. Featuring terrific performances by its young leads, the film marks an auspicious feature debut for its writer-directors.

“The story begins with Elliot (Jeremy Allen White, Shameless) experiencing a strange pain in his groin during a one-night stand. He discovers that he’s suffering from a form of cancer called Ewing’s sarcoma, which has resulted in a tumor on his pelvic bone. Around the same time, while waiting for a subway train he encounters Mia (Maika Monroe, It Follows), a frequent customer at the sandwich shop where he works, and impulsively asks her out.

“The two are soon involved in a passionate relationship, with Mia being lovingly supportive of her new boyfriend as he’s undergoing physically and emotionally debilitating chemotherapy treatments. Rather than drive them apart, Elliot’s illness seems to deepen their relationship, and he impulsively proposes marriage. For a while, the aftermath of the ‘shotgun wedding,’ as Mia describes it to Elliot’s concerned parents, proves happy. But even as Elliot is given a clean bill of health after successful surgery, the two young people begin to realize that their relationship is falling apart.

“While the pic’s tone is generally serious, it never becomes maudlin despite the tear-jerking subject matter. It also includes some genuinely funny episodes, such as a fantasy sequence involving Elliot’s efforts to become aroused while attempting to bank his sperm should his cancer prevent him from siring children; the couple giddily cavorting after ingesting ecstasy (but not before Googling ‘What happens when you take MDMA and have cancer?’); and their attempts to recruit a female participant to fulfill Elliot’s dream of having a threesome.

“The Generation Z demographic will certainly relate to such things as the film’s depiction of modern dating rituals like Tinder; unfulfilling jobs; roommates who spend their time bingeing on true-crime documentaries; and Elliot’s dreams of designing a new app. What impresses, though, is how effectively After Everything taps into universal themes involving the difficulties of sustaining relationships. And the way in which we can sabotage our future in an instant is perfectly encapsulated in an angry encounter between Elliot and Mia in which he blurts out something that he’ll never be able to take back.

“The filmmakers have attracted a talented supporting ensemble for this indie effort, including Gina Gershon and Dean Winters as Mia’s mother and her new boyfriend, and Marisa Tomei as Elliot’s attentive oncologist. But it’s the hugely appealing White and Monroe who authoritatively carry the film, mining the material for all its pathos and humor and displaying the sort of chemistry more often aspired to than achieved in romantic films. They make it look easy, as do the talented filmmakers.”

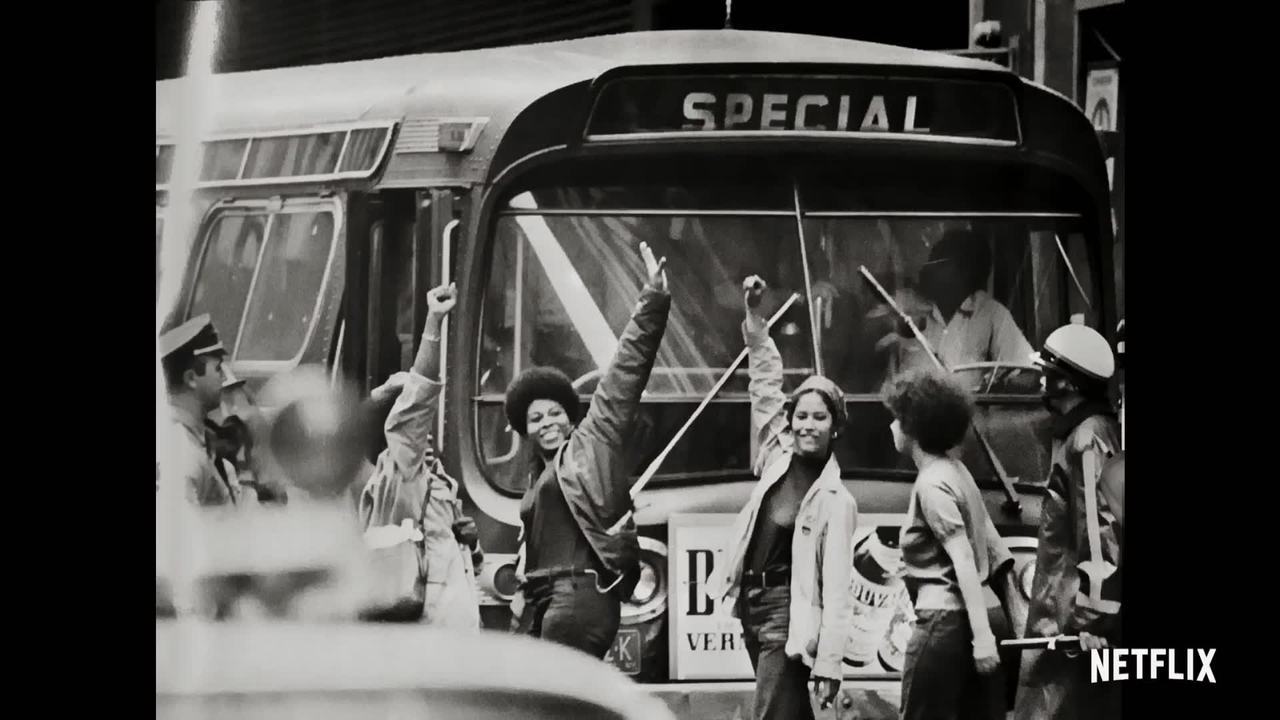

OCTOBER 12 (streaming on Netflix): Feminists: What Were They Thinking? (dir. Johanna Demetrakas) (DP: Kristy Tully) – RiverRun International Film Festival synopsis: “Feminism seems to be the scariest word in the English language, but not for those who experienced the game-changing awakening that was the Women’s Movement of the 1970s. Growing up in the 1950s and 60s meant not only second class citizenship legally, but second class human being-ship for women, not invited to the parties of medicine, art, law, education, science, or religion, except maybe as the secretary.

“In 1977, a book of photographs captured an awakening–women shedding cultural restrictions and embracing their full humanity. This documentary digs deep into the personal experiences of sexism and of liberation by revisiting those photos, those women and those times. The film follows this ever-evolving dialogue right into the 21st century, and takes aim at our current culture, vividly revealing the need for continued change.”

OCTOBER 12 (in theaters & streaming on Netflix): The Kindergarten Teacher (dir. Sara Colangelo) – Los Angeles Times review by Justin Chang: “‘Anna is beautiful / beautiful enough for me.’ So begins the lovely and, yes, beautiful first poem we hear composed by Jimmy Roy (Parker Sevak), who, at first, resembles an ordinary 5-year-old but might in fact be a pint-sized literary prodigy. The only person who notices is his kindergarten teacher, Lisa Spinelli (Maggie Gyllenhaal), who immediately takes him under her wing, eager to shield his talent from the indifference and banality of a world with no use for poetry.

“This is the story told in Sara Colangelo’s The Kindergarten Teacher, a deft and intelligent minor-key variation on a superb 2014 Israeli film of the same title. That earlier picture, written and directed by Nadav Lapid (Policeman), was a slow-to-boil psychological drama that built to a scalding indictment of the mindlessness and materialism that increasingly hold sway over contemporary life. Lapid’s social critique carried a particularly potent sting when directed at Israel, but it has been transplanted, seamlessly and with little dilution of impact, to the Staten Island neighborhood Lisa calls home.

“She lives there with a dependable husband (Michael Chernus) and two teenagers (Daisy Tahan and Sam Jules), who do things a lot of teenagers do — eat pizza, throw pool parties, stare at their phones — and who are sullen and non-communicative in ways that parents and children will instinctively recognize. But there is nothing reassuring about that recognition, and the movie regards these moments of estrangement and apathy less as normal phases of young adulthood than as troubling symptoms of a culture in decline.

“You can take or leave that thesis, but The Kindergarten Teacher moves too swiftly and absorbingly to brook much argument in the meantime. Lisa responds to her domestic discontentment by throwing herself into her teaching, determined to at least mold the more impressionable minds in her midst. After school, she seeks to ward off her own intellectual decay, and perhaps unlock talents that she’s never had a chance to explore, by attending a poetry-writing class. (At the risk of telegraphing a later plot twist a bit too blatantly, her teacher is played by Gael García Bernal.)

“The moment when Jimmy first recites his poem, pacing back and forth in the classroom as though lost in a fugue state, brings Lisa’s artistic aspirations and pedagogical instincts together. Lisa is struck by the poem’s elegant structure and subtle depth of feeling and also floored by the possibility that its young author — in all other respects a rowdy, adorable and utterly normal kid — might have an exceedingly rare gift.

“In cultivating that gift, Lisa initially seems to be doing an educator’s due diligence, as when she presses his somewhat flighty nanny, Becca (Rosa Salazar), to pay attention and write down any poems she hears him recite. She reaches out to Jimmy’s similarly neglectful dad (Ajay Naidu), who spends most of his time running a Manhattan bar, and also Jimmy’s uncle (Samrat Chakrabarti), a wordsmith who seems to have instilled a love of poetry in his nephew to begin with.

“What gives The Kindergarten Teacher its peculiar force is how quickly it acknowledges the darker side of Lisa’s nurturing impulse — and how successfully it ushers us into a strange complicity with her all the same. Colangelo, who made her feature debut with the 2014 drama Little Accidents, balances the story’s myriad conflicting tensions with admirable lucidity. That’s another way of saying that she keeps the camera steadily trained on Gyllenhaal, whose brilliantly discomfiting performance anchors every scene.

“Lisa is hardly the first schoolteacher to employ a measure of manipulation as an educational tactic. But there is something particularly ruthless about the way she wraps a steely disposition in a warm, cajoling smile, her eyes twinkling with affection even as they penetrate your every defense. For all the attention Lisa showers on Jimmy — waking him during naptime for private lessons, having him accompany her to a Manhattan poetry reading — she refuses to infantilize him or treat him as anything but the genius she believes him to be. She demands a level of commitment commensurate with her own.

“And Jimmy, played with remarkable self-possession by Sevak, responds to Lisa’s orders with a mix of obedience and confusion that feels like an implicit rebuke. On the surface, her increasingly desperate actions might seem reckless and deluded to the point of stupidity, but her motivations to the end remain irreducibly, gratifyingly complex. It’s hard not to suspect that Lisa might be driven in part by jealousy, rooted in a deep awareness of her own failures. It’s also hard not to discern an element of seduction, more psychological than sexual, in the way she tries to coax Jimmy’s talent into the light.

“But it may be hardest of all to completely dismiss Lisa’s convictions, or the sense that her behavior, extreme though it may be, is rooted in a completely accurate assessment of a morally and intellectually bankrupt society. The Kindergarten Teacher may offer a less audacious, more stylistically muted version of its predecessor, but by the time its quietly perfect final shot arrives, the movie has reached the same provocative conclusion. It’s not poetry, exactly, but it’s pretty shattering prose.”

OCTOBER 12: Over the Limit (dir. Marta Prus) – Quad Cinema synopsis: “The title says it all in this mesmerizing, relentless documentary following Russian rhythmic gymnast Margarita Mamun’s grueling journey to the 2016 Olympics. Herself a former gymnast, Prus opts for a fly-on-the-wall approach, capturing not only Mamun’s remarkable physical feats (leaping, tumbling, and unfathomable balancing acts) but the evident psychological strain of the sport—and of her demanding coaches, whose idea of motivation consists of hurling abuse from the sidelines. Their best advice? ‘Find your inner harmony and touch up your eyebrows.'”

OCTOBER 12: Sadie (dir. Megan Griffiths) – The Seattle Times review by Moira Macdonald: “‘Everybody’s got details,’ says an old man in the locally filmed drama Sadie, whittling away at a stick. “You gotta know how to carve them.’ Luckily, Seattle-based writer/director Megan Griffiths (The Night Stalker, Lucky Them, Eden) knows exactly how to carve her characters — with the help of a skilled cast of actors. Though it addresses big themes — children’s exposure to violence; opioid addiction; single parenting — Sadie is at its heart an intimate story, about a mother and daughter and a man who seems to come between them. But its honesty and power makes it feel large; you live among these characters in their weary trailer park, aching for them.

“Filmed in rain-soaked Everett and punctuated by the sound of a train whistle on its way to somewhere else, Sadie quickly introduces us to its title character (local actor Sophia Mitri Schloss, perfectly capturing the quicksilver ice of being 13) who lives with her mother, Rae (the always splendid Melanie Lynskey). Sadie idealizes her military father, who’s been overseas for years; the lonely Rae, who knows things about her marriage that her daughter doesn’t, is ready to move on. Along comes a stranger: Cyrus (John Gallagher Jr.), who attracts the eye of both Rae and her friend Carla (Danielle Brooks). Things get messy, and Sadie — her eyes narrowing as if they’re being sharpened to a point — thinks she knows how to solve the problem. But she’s 13, and of course she doesn’t.

“Much of the pleasure of Sadie is watching its beautifully carved details: Lynskey’s soft, hopeful line readings, suggesting a woman who’s known disappointment and yet still believes something better might come along; Brooks’ way of hinting at a world of pain behind Carla’s sassy-best-friend persona; the tired browns and grays of the characters’ homes, where the air feels damply cold and water perpetually drips from the gutters. But it’s at its most mesmerizing when fixed on Schloss’ unblinking gaze; a child at war with forces — and consequences — that she can’t yet understand.”

OCTOBER 12: Stella’s Last Weekend (dir. Polly Draper) – City Cinemas Village East Cinema synopsis: “Oliver (Alex Wolff) is a Queens high school senior who is madly in love with Violet (Paulina Singer), a fellow classmate who is the girl of his dreams. Oliver’s older brother, Jack (Nat Wolff), is not so lucky with his love life, having made a real connection with a girl several months earlier, who suddenly dropped him without any explanation. When Jack comes home from college for a special celebration of Stella, the family’s beloved but aging dog, he soon discovers that the girl who broke his heart is the very same Violet who has stolen Oliver’s heart. A series of comic complications ensue as the romantic rivalry between the brothers escalates.”

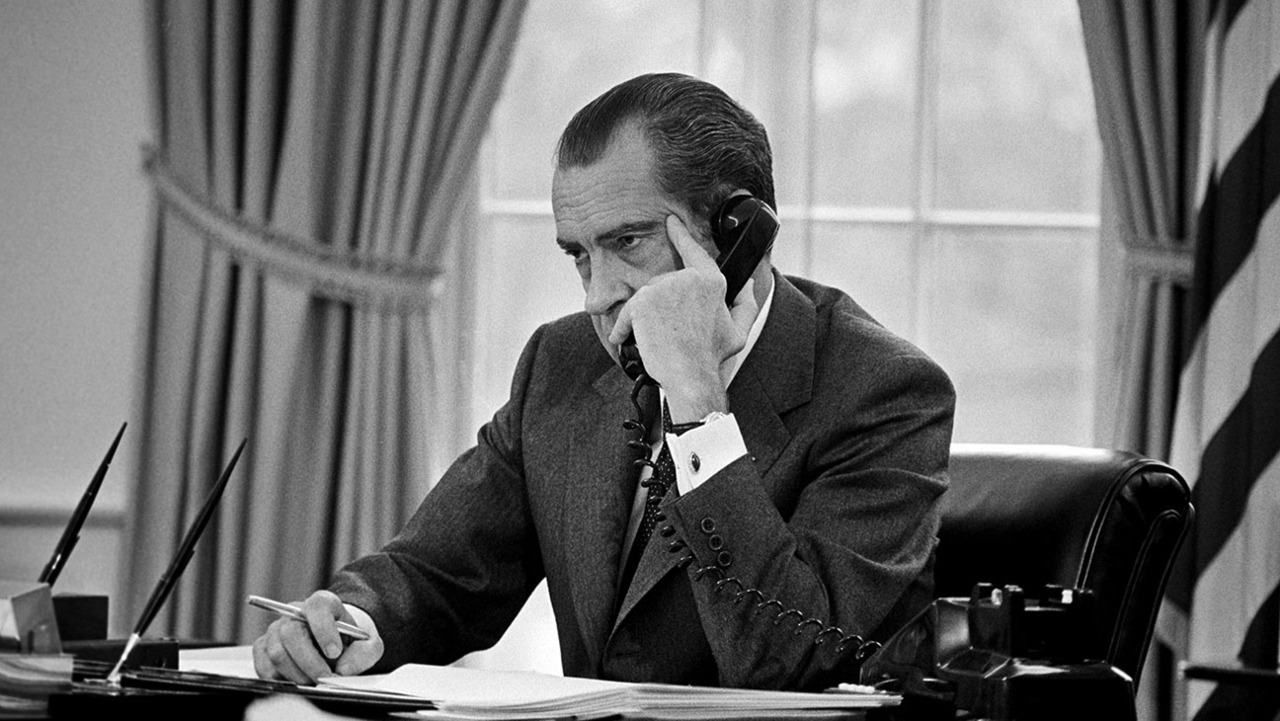

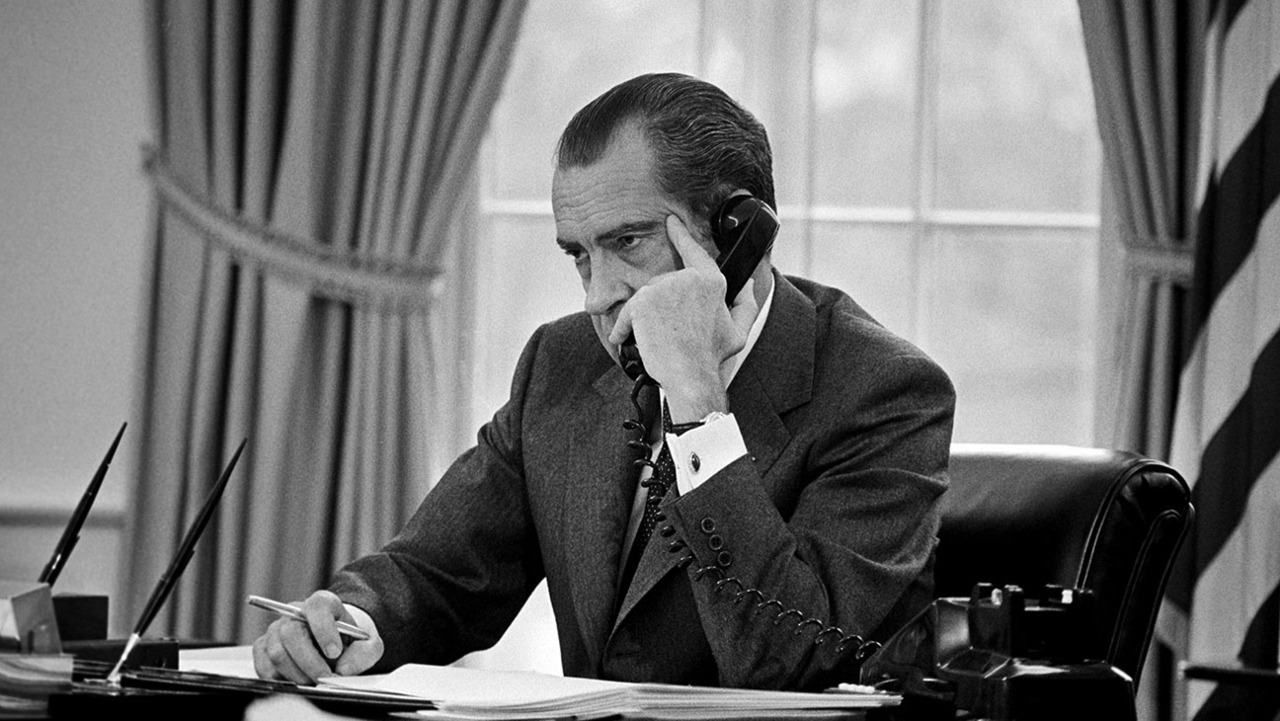

OCTOBER 12: Watergate (dir. Charles Ferguson) (DPs: Shana Hagan, Yuanchen Liu, Dennis Madden, Daphne Matziaraki, Morgan Schmidt-Feng) – Cinema Village synopsis: “Watergate tells, for the first time, the entire story of the Watergate scandal, from the first troubling signs in Richard Nixon’s presidency to Nixon’s resignation and beyond. (Surprisingly, despite many excellent books and documentaries, the story of the Watergate scandal has never before been told in a truly comprehensive way.). But crucially, the film also situates Watergate in the context of all the issues it raised – many of which, of course, now resonate powerfully with current events.”

OCTOBER 16 (on digital): The Devil We Know (dir. Stephanie Soechtig with co-dir. Jeremy Seifert) – Variety‘s Sundance Film Festival review by Dennis Harvey: “The list of modern conveniences that will sooner or later take a toll on your — or somebody’s — health gets a lot longer with The Devil We Know. Stephanie Soechtig’s documentary exposes the apparently decades-long efforts by the DuPont corporation to deny the adverse effects of chemicals used in the manufacture of Teflon kitchenware, which they knew about at least as early as 1982. They’re still denying them, even as birth defects and other problems have increasingly surfaced among factory workers and nearby residents whose water has become polluted with industrial waste.

“This cogent, powerful indictment will most likely make its primary impact in small-screen exposure — though the Trumpian war on industrial and environmental regulation lends it a particularly urgent relevancy.

“What we first see is rough old video footage shot by Wilbur Tennant, a West Virginia farmer who’d sold part of his property to DuPont. They’d said they’d use the land only to dispose of ‘non-hazardous’ substances, but he soon suspected otherwise — particularly once dogs, wildlife and his entire livestock herd died. His belligerent citizen activism was later echoed by Joe Kiger, an area schoolteacher turned whistleblower who grew uneasy about the impact of chemicals in drinking water, then more so as his questions to authorities (including the Environmental Protection Agency) were brushed off with evasive PR blather.

“Their community of Parkersburg, WVa., is the epicenter of woes from commercial use of C8, a compound long used in the manufacturing that is the town’s economic engine. Its variants are deployed not just in creating non-stick cookware, but everything from microwave popcorn bags to waterproofed Patagonia sportswear. There’s little discussion here of the potential impact on everyday consumers, beyond the fact that C8 can now be found in the bloodstream of nearly every American, and that it has a very long shelf life in landfills.

“Those who worked directly with the chemicals at the plant were the first to suffer ill health effects, including cancer and birth defects that in the case of Bucky Bailey required more than 30 corrective surgeries when he was just a child. Eventually the problems began drifting downriver to other towns whose water was contaminated by the same factories’ pollution.

“Damning evidence is presented here that DuPont knew of C8’s impact but hid and denied that knowledge — then took over production of the hazardous substance from 3M when that company stopped making the stuff due to the research findings. A class-action suit finally staggered toward a heavily compromised win for residents. Yet even that seemed to offer little assurance for the future: DuPont and others remain free to slightly change C8’s chemical formula and continue producing it, as indeed they’ve done.

“Mixing footage of public hearings, news reports and corporate ads, plus input from scientists and activists, The Devil We Know is a riveting tale of long-term irresponsibility and injustice. It’s made particularly infuriating by the contrast between workers who placed all trust in their employers’ goodwill, and the government agencies that did very little to intervene when it became obvious those workers were being often fatally victimized by knowing corporations. As with numerous other environmentally focused docus of late, this one underlines the extent to which the EPA has its hands tied by Byzantine federal/state control limitations, as well as excessive influence from the very corporate interests it should be patrolling.

“Soechtig presents an unusually engrossing docu for this type of subject, with human interest always in the forefront despite the complex timeline of events, issues and information presented. The director, whose prior docs Under the Gun and Fed Up were also well-received exposés (of the gun lobby and obesity-promoting food industry, respectively), presides over an expert assembly that’s sharp in every department.”

OCTOBER 17: Charm City (dir. Marilyn Ness) – IFC Center synopsis: – “On the streets of Baltimore, shooting is rampant, the murder rate is approaching an all-time high and the distrust of the police is at a fever pitch. With nerves frayed and neighborhoods in distress, dedicated community leaders, compassionate law-enforcement officers and a progressive young city councilman try to stem the epidemic of violence. Filmed over three tumultuous years covering the lead up to, and aftermath of, Freddie Gray’s death in police custody, CHARM CITY is an intimate cinema verité portrait of those surviving in, and fighting for, the vibrant city they call home. Directed by renowned documentary producer Marilyn Ness (Cameraperson; Trapped; E-Team).”

OCTOBER 19: Brewmaster (dir. Douglas Tirola) (DP: Emilie Jackson) – Cinema Village synopsis: “Brewmaster artfully captures the craftsmanship, passion and innovation within the beer industry.The story follows a young ambitious New York lawyer who struggles to chase his American dream of becoming a brewmaster and a Milwaukee based professional beer educator as he attempts to become a Master Cicerone. Helping tell the story of beer are some of the best-known personalities in the industry including Garrett Oliver, Jim Koch, Vaclav Berka, Ray Daniels, Charles Papazian and Randy Mosher. Brewmaster creates a cinematic portrait of beer, those who love it, those who make it and those who are hustling to make their mark.”

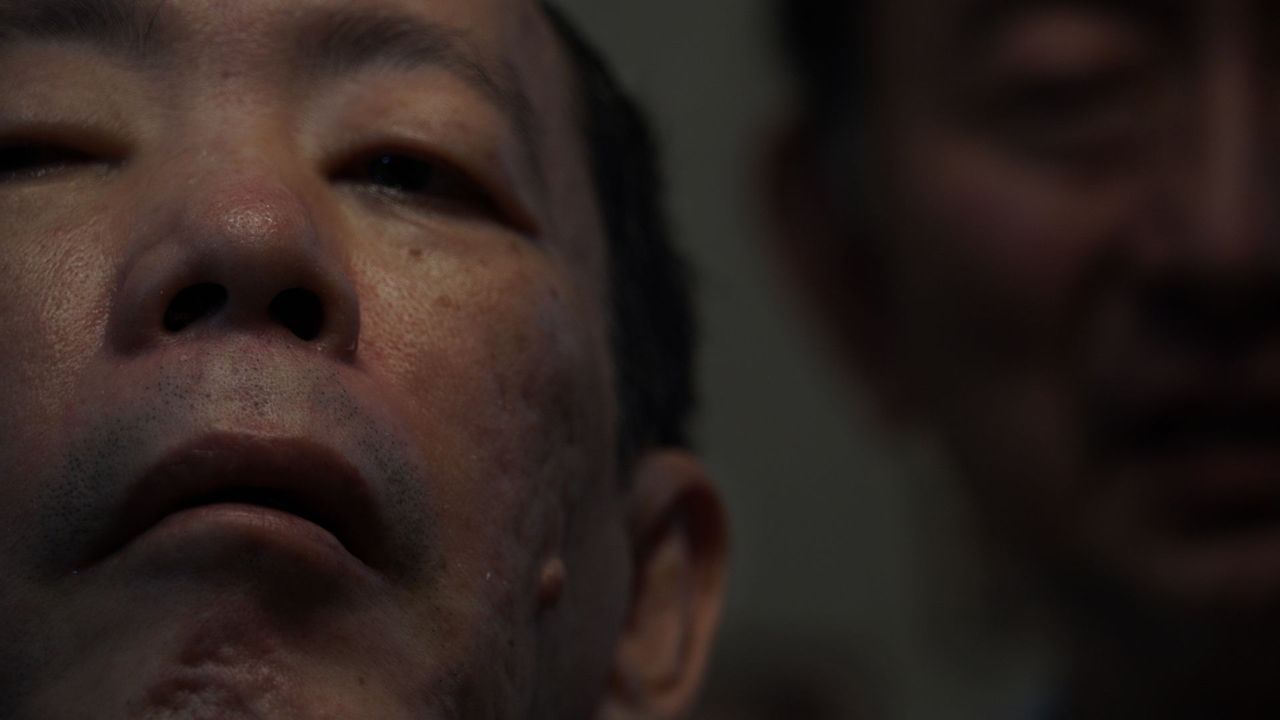

OCTOBER 19: Caniba (dirs./DPs: Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Verena Paravel) – Museum of the Moving Image synopsis: “This new film from the pioneering directors behind the landmark documentary Leviathan is a discomfitingly experiential portrait of unacceptable desires. On June 13, 1981, 32-year-old Sorbonne student Issei Sagawa was arrested in Paris after being caught discarding two suitcases containing the remains of his Dutch classmate, who he had murdered and begun to consume. Declared legally insane, he returned to Japan, where he has been a free man ever since. Though ostracized from society, Sagawa has made a living off his crime by writing novels, drawing manga, and appearing in salacious documentaries and sexploitation films. Meanwhile his brother, Jun Sagawa, harbors extreme impulses of his own. With Caniba, Véréna Paravel and Lucien Castaing-Taylor—titans of Harvard’s celebrated Sensory Ethnography Lab—pursue a minimalist audiovisual strategy that is in some ways the inverse of the maximalist Leviathan, fostering unease and reflection through deceptively meandering conversation and subtly shifting focus. And as such Caniba is a singular cinematic experience: a horror movie by way of the documentary interview.”

OCTOBER 19: Can You Ever Forgive Me? (dir. Marielle Heller) – New Yorker review by Richard Brody: “Melissa McCarthy has been in need of a substantial dramatic role for quite a while, and in Can You Ever Forgive Me?, which opens on Friday, she gets one—and makes the most of it. But it’s clear, from the very first scene, that the movie, directed by Marielle Heller, is far more than just a showcase for McCarthy’s artistry. The film tells the story of the real-life writer and literary forger Lee Israel, and is based on Israel’s memoir of the same title. It is a fiercely composed, historically informed, and richly textured film, as insightful regarding the particularities of the protagonist as it is on the artistic life—and on the life of its times.

“The action begins in 1991 and is set in Manhattan. Lee, a proofreader working an overnight shift in a law firm and an object of her younger colleagues’ derision (which she repays in sarcasm), is fired on the spot, not for drinking on the job (which she’s brazenly doing) but for cursing out the young supervisor who reproaches her. Lee brusquely finishes her tumbler of Scotch, dumps the ice cubes into the garbage can under her desk, and puts the glass into her tote bag before leaving. The gestures have a pugnacious elegance; the text (from a script by Nicole Holofcener and Jeff Whitty) is rich in epigrammatic flair. Above all, Heller achieves an extraordinary, tense balance of moods and tones that yields sharp dramatic insight. Lee’s playful inventiveness and flamboyant attitudes do more than fuse with recklessly self-destructive behavior; they also incite and inspire it.

“Can You Ever Forgive Me? is set at the crossroads of money and art. Lee was once a biographer who appeared on the Times best-seller list, but she can no longer find a publisher for any of her projects of cultural history from a woman’s perspective. Her main plan, a biography of Fanny Brice—the comedian who was portrayed by Barbra Streisand in Funny Girl—comes to naught. She’s never held a day job before, and her acerbic, cantankerous demeanor gets in the way of her keeping one now. In any case, as the movie makes clear, the research-heavy, travel-based work of nonfiction requires both time and money. The new, celebrity-heavy world of corporate-merger publishing has little room for her. No advances are forthcoming. Lee can’t pay her rent, nor can she pay the veterinarian to care for her aging cat. She even steals toilet paper (and other, more lavish commodities) from a publishing party. When she’s compelled to sell a prized possession—a letter Katharine Hepburn wrote her when she was working on a profile of the actress—a light bulb turns on in her mind.

“After finding, by chance, a letter from Brice between the pages of a library book, Lee steals it and tries to sell it. Learning that its value would be increased if its contents were spicier, she spices it up with a flourish of a P.S. that seems to emerge from her own mind-meld with her cherished subject. Lee quickly morphs from a biographer into impersonator, relying on the same skills that she used to enter into imaginative sympathy with the people she wrote about. She becomes, in effect, a writer of docufiction, setting up a cottage industry of fabricated letters from celebrities she ‘gets,’ including Marlene Dietrich, Noël Coward, Edna Ferber, and Dorothy Parker—writers whose identities are plotted on the dimensions of womanhood, gayness, Jewishness, sharp wit, and artistic talent. (The movie revels in the material specifics of her deceit, involving old manual typewriters, replicated letterheads, signatures that she forges by using an upturned TV set as a lightbox, and paper that she ages in her oven.)

“Lee is single, but is still in close mental proximity to her ex, Elaine (Anna Deavere Smith). She’s also back in touch with a former acquaintance, Jack Hock (Richard E. Grant), a gay man who’s H.I.V.-positive, homeless, free-spirited, defiant, and—like Lee herself—quietly and proudly desperate. As their friendship grows, he takes note of Lee’s sudden and unwarranted solvency and asks about it. ‘Can you keep a secret?’ she asks. ‘Who would I tell?’ he replies; ‘All my friends are dead.’ The devastation of the AIDS crisis is also at the center of Can You Ever Forgive Me? and Heller, pointedly and surely, creates a work of mourning for its victims and of gratitude for the community of activists who fought for rights, respect, and treatment—and cared for the stricken among them.

“The movie is sharply historically informed, down to its urban geography. The bar that Lee frequents, and where she meets Jack, for the first time by chance and later by design, is Julius’, a longtime gay bar in the West Village and the site, in 1966, of the Sip-In, a historic protest against the city’s anti-gay laws and the bar’s own discriminatory practices. It’s not expressly a story of activism; Jack is depicted as an apolitical hedonist (he also gets involved in Lee’s criminal scheme), but he, too, is in his way an artist (also a heedless and sometimes destructive one)—an artist of life, whose ardent vitality contrasts cruelly with his fate.

“The decimation of the gay community marches alongside the decimation of the city’s artistic culture. Can You Ever Forgive Me? is a movie of endings, a mournful film, suffused with an air of doom, in which the sort of genteel literary poverty that kept Lee going can no longer be sustained. Even the core of her art, her caustically aphoristic brilliance, comes off as a defense mechanism, not merely against the usual buffeting winds of life but against prying and suspicion from an age when L.G.B.T. people were the subject of severe legal discrimination and social prejudice. The scintillating verbal inventiveness that’s essential to her art, and to her personal allure, is also an electrified fence that enforces privacy, even at the price of desperate solitude.

“Heller’s geographic specificity includes appealing glimpses of some of the borough’s most picturesque bookstores—happily, ones that survive to this day, such as Argosy, Westsider, the Housing Works Bookstore Café, and Logos. With their venerable charm (filmed lovingly by Heller, with incisive, nearly matte-seeming cinematography by Brandon Trost), they nonetheless have the fragile air of survivors of a series of storms—and Lee’s own fraudulent sales of fabricated memorabilia turn out to be among the threats that these businesses face.

“These sales, and the confidence game that she plays with dealers in order to make them, are dramatized in outrageously careful criminal detail—as well as in their personal implications, both for Lee and for the buyers. In particular, a woman named Anna (played by Dolly Wells with a tremulous grace), who admires Lee’s voice and bearing, falls further under her spell, with painful results. The entire cast performs at a perfect pitch of slightly heightened tension that lends their range of emotions—confrontational worldliness, brave-faced struggle, solitary pride—a striving pitch of urbane intensity. In particular, Grant, as Jack, seems to bear a vast history of pleasure and trouble with a breezy flair, and, as Lee’s agent, Jane Curtin delivers hard wisdom with an intellectual boxer’s devastating deftness.

“Above all, McCarthy infuses the role of Lee with many levels of imagination. McCarthy is one of the most verbally inventive actors of the time and, playing a person of learning, imagination, and experience, her verbal inventiveness is no mere comedic adornment but the core of the character’s identity, and she flaunts it with a pathos that suggests the essential doubleness of art, its element of gaudy artifice as well as of intimate self-revelation. The pivot of the action is Lee’s unwillingness to expose her own life and character to the scrutiny and criticism of readers, and the gap that her inhibition—one born of her fortress of privacy—makes between her artistic soul and her artistic voice.

“The movie never excuses or minimizes Lee’s crimes (which eventually include the theft and sale of authentic letters); yet it considers them in the paradoxical light of her own talent, which, she asserts, was revealed more definitively in those forgeries than in her prior avowed works. The confessional book itself, on which the movie was based—and in which Israel cites and discusses these fraudulent works of her authentic artistry—provides a fascinating nonfiction view of these fictions. But the movie adaptation reaches beyond its source to broaden its backdrop and evoke resonant depths of mood, context, history, and perspective. It’s one of the rare movies that give a cinematic identity to literary creation, that virtually bursts with the athletic pleasure of imagination. Heller’s images are simple and poised, lucid but weighty—they vibrate with the expressive force that they condense and contain.”

OCTOBER 19 (in theaters & on VOD): Change in the Air (dir. Dianne Dreyer) – Synopsis from the film’s official website: “Change in the AIr opens in a modest home on a quiet street. An old man, Walter Lemke (M. Emmet Walsh), skips breakfast with his wife, Margaret (Olympia Dukakis), walks outside, and steps in front of an oncoming car. Deliberately. Moody Burkhart (Aidan Quinn), the police officer who responds to the accident, inquires about the woman, Wren Miller (Rachel Brosnahan), who placed the emergency call, but when he knocks on Wren’s door, she hides.

“The following day, Jo Ann & Arnie Bayberry (Mary Beth Hurt and Peter Gerety) return from a bird-watching expedition. Their next-door neighbor, Donna (Macy Gray), tells them Mr. Lemke is in the hospital and that she’s found a new tenant to sublet her apartment: Wren. When Mr. Lemke returns home, Jo Ann sees him sitting by himself in his front yard. She drags her lawn chair down the street and sets up beside him – invading his space with the best of intentions. Walter never says a word; Jo Ann never stops talking.

“Meanwhile, Josh (Satya Bhabha), the local mailman, daily delivers a large bag of letters to Wren’s door. In the days that follow, Jo Ann’s vigil on the Lemke lawn expands along with her fascination with Wren. But now it’s not just Jo Ann who is intrigued.

“This story embraces the imperfections that make us human, offers a way to set ourselves free and asks us all to take a good, long look at the wild birds in the sky.”

OCTOBER 19: An Evening with Beverly Luff Linn (dir. Jim Hosking) (DP: Nanu Segal) – Newsweek review by Andrew Whalen: “We are all more like characters in An Evening with Beverly Luff Linn than anyone is likely to admit. Following the tangled relations between a vanload of people in the lead up to a mysterious event at the Moorhouse Hotel, the evening with Beverly Luff Linn itself, director Jim Hosking’s follow-up to 2016’s The Greasy Strangler isn’t as fevered (he co-wrote this film with David Wike), but does cut closer to the childish heart of humanity.

“Beverly Luff Linn doesn’t have the same defenses as The Greasy Strangler, which layered Riki-Oh ’s gorey plastic bodies, prosthetic penises and a strange, almost arthouse ending over its essentially puerile (in a good way!) appeal. Luff Linn opens in similar territory, with profoundly doltish characters working a business that seems unworkable, in this case a franchise coffee shop that mostly deals in carnival-cup cappuccinos that disgust customers. But Beverly Luff Linn never offers a retreat into anything as surreal as a grease-covered serial killer, instead sticking close to more familiar discomforts, beginning with store manager Shane Danger (Emile Hirsch) awkwardly firing his wife, Lulu Danger (Aubrey Plaza), according to corporate edict.

“Shane’s feelings of inadequacy lead him to rob Lulu’s brother Adjay’s vegan shop of its cash box, which Lulu quickly absconds with, hiding in the Moorhouse with inept hired muscle and wannabe drifter-adventurer Colin Keith Threadener (Jemaine Clement). As Colin pines for Lulu from across the gap between their twin beds, Lulu pursues her great lost love, in town for a special engagement, Beverly Luff Linn himself (Craig Robinson).

“At first, An Evening with Beverly Luff Linn feels like it’s playing with pieces of melodrama, crashing absurd characters against each other and watching them tangle. Aubrey’s Lulu brings to every encounter a faux-aristocratic contempt, smoldering out from her mothy, estate sale wardrobe as she contemptuously holds Colin aloft. Shane waves a gun around and stalks Lulu, but is completely absent of menace, thanks in part to the blonde wig and Rita Hayworth sunglasses that make up his disguise. That all of the romantic subplots swirl around Luff Linn, who speaks entirely in grunts and growls, seems to highlight how An Evening with Beverly Luff Linn doesn’t care about the content of its characters’ torments.

“It’s not a notion Beverly Luff Linn is quick to counter, especially when so much of what’s fun and funny about it is pitched at the exact level of appeal of playing with your food. (Even better than the cheesy onion rings Colin scarfs are the hotel bar drinks, each of which come with one of those jumbo Tootsie Roll logs as a stirrer.) Characters call each other names like ‘big fat penis face,’ while Lulu self-importantly chides Colin for eating bar nuts by telling him ‘You know those might have poo on them, you don’t want to get poo in your mouth, do you?’

“But then a strange thing happens: their childishness begins to feel less like flippancy and more like raw pathos. Colin’s laborious story of how he got his name (something to do with an uncle and… teeth?) isn’t poignant in itself, but Luff Linn leaves Clement the room to breathe a tragic, hangdog energy into his character. Rodney Von Donkensteiger’s (U.K. comic actor Matt Berry, opening another front in his slow invasion of American comedy) overbearing protectiveness of Luff Linn begins to feel less like a joke and more like true romance (which pays off sweetly in an after credits sequence).

“The mechanisms of this drama continue to be juvenile, but begin to feel less like immaturity and more like a sympathetic guilelessness, instantly identifiable to anyone who’s felt the emptiness at the heart of adulting like a boss. When a character condescendingly orders, ‘The Earl Grey, I’m sure you haven’t heard of it,’ I could feel the barb reach back and burst my own embarrassed memories of performing sophistication.

“What the actual, magical evening with Beverly Luff Linn reveals I will not spoil, except to say I was surprised by its romantic earnestness. An Evening with Beverly Luff Linn is an odd combination of characters who talk like playground bullies and an almost mystic somberness, as if ‘Twin Peaks’ invaded Best in Show. But what’s most impressive is how much open emotion emerges from its eerie, fart-haunted world.”

OCTOBER 19: Galveston (dir. Mélanie Laurent) – Film School Rejects’ SXSW review by Matthew Monagle: “Here’s to films about sad-sack professional killers and the sex workers they love. For decades now, Hollywood has been telling elegiac stories of people on the run from lives of violence. Over time, this narrative has become cinema’s answer to the jazz standard, a familiar conceit that gives its performers ample opportunity to show off their own individual style. Mélanie Laurent’s Galveston is one such example within the genre; while there’s a thread of familiarity throughout the movie, her steady hand and the powerful performances of her leads give Galveston its own alluring sense of self.

“Roy Cady (Ben Foster) is dying. A lifelong smoker, Cady has just been given a terminal diagnosis by his doctor, and what little life Cady has cobbled together in New Orleans seems suddenly unimportant in light of his illness. He doesn’t care, for example, that his employer (Beau Bridges) seems to have stolen his girlfriend out from underneath him, but his boss cares, quite a bit, and would like to speed up Cady’s exit from this world. That’s why Cady is suspicious when he is told to intimidate a local lawyer but not to bring a gun; in the inevitable firefight, Cady leaves behind three dead bodies and gains Rocky Arceneaux (Elle Fanning), a sex worker whose only real sin is that she was in the wrong place at the wrong time.

“After the two manage to calm their nerves with a few shots of whiskey – ‘Cheer up. You’re alive. I’m buying.’ – Arceneaux and Cady head out west, stopping on the Louisiana border to pick up her little sister along the way. Before long, they find themselves in the poorest part of Galveston, Texas, not sure what to do next but knowing their time together is probably limited. With nothing to lose and not much time left among the living, Cady begins looking for ways to potentially set up Arceneaux and her sister when he’s gone.

“Few actors embody the threat of violence quite like Ben Foster. From his recent supporting roles in Hostiles and Hell or High Water – not to mention his off-Broadway stint as Stanley Kowalski in A Streetcar Named Desire – Foster seems born to play the abuser, a man hellbent on punishing those around him for the injustices he feels he’s been offered by the world. This sometimes leads us to forget Foster’s nuance as an actor. Foster finds little moments of fragility amidst the bravado and outrage; in one scene, for example, he contemplates a cigarette before choosing to light it, making a clear decision to embrace his end when it occurs.

“And then there’s Elle Fanning. Those familiar with her work in The Neon Demon know that Fanning possesses uncanny depth for an actress her age. With Arceneaux, she convincingly moves between innocence, innocence lost, and a calculated innocence that she uses to earn the trust of those around her. Galveston is cruel to Arceneaux, as it is to most of its characters, but Fanning’s performance keeps her character from ever falling into cliche. To borrow a phrase from another story set in Texas, there is a part of herself that she keeps just for herself; she has power, even if it’s just in the tough decisions she makes to keep ends together.

“Galveston also presents an authorial puzzle for those willing to do the work. Rody Cady is unquestionably a character born from the mind of author Nic Pizzolatto; abusive, drunk, and quietly self-destructing, Cady possesses many of the characteristics we recognize from True Detective, the series that catapulted Pizzolatto to stardom (and just as quickly became his downfall with a lackluster Season 2). But unlike the characters in that series, Cady is deprived his victimhood by the women around him. His ex-girlfriend and the manager of his motel both see through Cady’s facade, and Rocky’s relationship with Cady is given a degree of independence by Fanning’s powerful performance. It’s hard not to wonder where Pizzolatto ends and where Laurent begins in the narrative. Galveston will undoubtedly make for a fine dissertation on adaptation one day.

“And what of Galveston itself? Outside of the film’s ill-conceived framing device of an impending hurricane, Galveston’s story is well-matched to its coastal setting. This is a city that has been wiped away by countless storms, only to rebuild unevenly across economic lines; at times, Galveston feels more like a movie borrowing from The Florida Project than a traditional crime thriller. Laurent delves into the poorest parts of the city to shoot her film – one particular tracking shot is like a guided tour of economic anxiety – allowing Galveston a sense of location unique to many of its peers. If Galveston is indeed just another hoary standard, then it proves more about the talent of the performer than the quality of the song. No noir can truly disappoint when you’ve got East Texas on your side.”

OCTOBER 19 (NYC), OCTOBER 24 (LA): On Her Shoulders (dir./DP: Alexandria Bombach) – RogerEbert.com review by Nell Minow: “Four years ago, Nadia Murad Basee Taha was a teenager living in a Yazidi farm community in the Sinjar district of Iraq when ISIL took over the town, murdered 600 people, and captured the women and girls as sex slaves. She escaped three months later and has spent most of the time since speaking out on what happened to her and her people. This month, she was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. This award-winning documentary tells her story.

“Director Alexandria Bombach understands that there are two stories here. First there is the inspiring story of a young woman who had no ambitions of becoming a world figure but who overcame unthinkable loss and trauma by devoting herself to helping others. Then there is the story of a young woman who is forced to relive her most painful experience over and over and who is constantly bombarded by the overwhelming needs of others, from the photo-op sympathy of politicians and journalists to the heartbreak of her surviving community, most still living in refugee camps, who sob in her arms and beg her to get them some help.

“Mostly, Bombach just lets the camera sit quietly as Murad goes through her exhausting schedule of meetings, media appearances, and book signings. She captures some telling images: a refugee lowering his fishing line into the ocean through a cracked panel in the fence around the camp, Murad touching a heavy chain around a locked gate, Murad’s comment on seeing a school marching band practice, ‘If this were in Iraq, someone would blow himself up.’ She gazes into a beauty salon mirror as her hair is wrapped around a curling iron. In one of her appearances before a UN assembly, we will learn something about what her long hair means to her.

“Murad wants the world to hear her story and she is focused on a particular goal. She wants to be on the agenda of the meeting of world leaders in New York, to ask them to declare what happened to her people an official genocide and to give them justice. The process for getting the opportunity to speak to the assembly of Presidents and Prime Ministers is a daunting one. Early in the film she is preparing for what amounts to an audition. She will speak to a committee at the United Nations, and if she passes muster, she can move up to the next level.

“The time limit is strict. Her rehearsal for the initial presentation is 50 seconds over time so she has to figure out what to cut. If she takes out too much detail, the plea for help will have no weight. If she takes out the plea, she will leave without presenting a challenge to be met. When she has to shorten the speech for the final version, she eliminates the call to the world leaders to imagine what it would be like to be enslaved by ISIS because ‘What’s the benefit of asking them to imagine?’

“The film’s most affecting moments are when Murad speaks directly to the camera. She says that the only way she can deal with what she has suffered is to devote herself to helping the other girls who suffered, too, but do not have the opportunity to bring their stories to the world. She says she feels worthless, and will always feel that way until her people get justice.

“She was content in her home in Sinjar, she tells us, doing chores, tending sheep, spending time with family, and hoping she could become a hairdresser, a place ‘where women and girls would see themselves as special.’ She wishes that people would know her as an excellent seamstress or athlete, not as a victim of ISIS terrorism.

“It is at best bittersweet when she is named a goodwill ambassador by the UN. Her title carries as much tragedy as honor: Goodwill Ambassador for the Dignity of Survivors of Human Trafficking. As Murad makes clear in her three minutes, there is no dignity without justice. There is only one border, she tells the presidents and prime ministers, ‘the border of humanity.’ We see this movie to learn who the young Nobel Peace Prize winner is, but in the end, it is about her challenging us to learn who we are.”

OCTOBER 19: The Waldheim Waltz (dir. Ruth Beckermann) – Metrograph synopsis: “When former UN Secretary General Kurt Waldheim ran for the presidency of Austria in 1986, he was suddenly haunted by the re-emergence of specters from his Nazi past, vehemently and disingenuously denied. Using archival material and her own vintage video footage of anti-Waldheim rallies which show anti-Semitism alive and well in the Europe of the mid-‘80s, Ruth Beckermann narrates this scintillating film, in which the combination of bald-faced lying by public figures, anti-media animus, and populist bully tactics speak all too clearly to our present moment.”

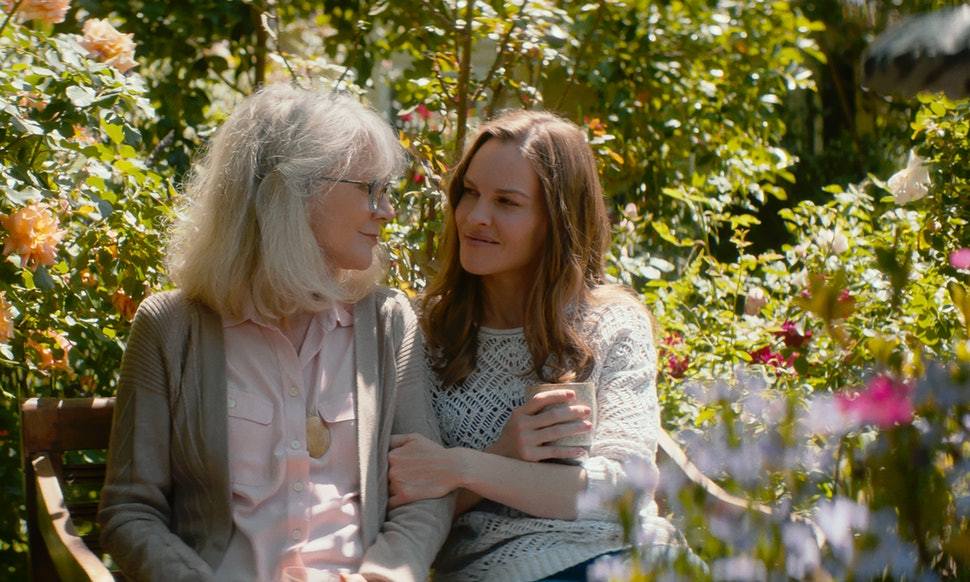

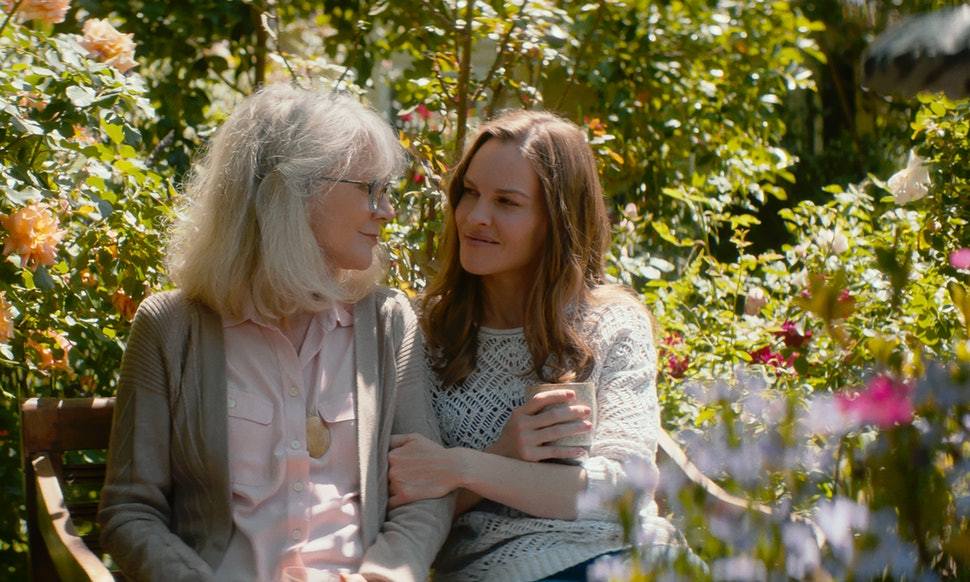

OCTOBER 19: What They Had (dir. Elizabeth Chomko) – Vulture’s Sundance Film Festival review by David Edelstein: “Introducing her exquisite debut feature, What They Had, at Sundance, the writer-director Elizabeth Chomko addressed the movie’s initiating event — a woman with Alzheimer’s reaching the last-but-one stage, number six — only obliquely. Chomko painted a larger picture.

“‘Memory,’ she said, ‘is a gift we’re given. I don’t want to take it for granted.’ And so, in the film, the camera occasionally lingers on photos and home movies of Ruth (Blythe Danner) and her husband, Bert (Robert Forster), as they were in their 20s and 30s; and Ruth is tasked to carry a picture in a locket that can remind her, fleetingly, who the man across the table from her is.

“Before I get too lachrymose, I should mention that the movie has a lot of great laughs: The characters speak their minds and then some. The main couple isn’t the old one but a pair of middle-aged siblings, Bridget (Hilary Swank), and Nicky (Michael Shannon), who call each names like ‘turkey’ and ‘dingle-fairy’ and whose conversations often end in shouting matches. Bridget has flown in from Los Angeles to take some of the burden off Nicky and has brought her daughter, Emma (Taissa Farmiga), who’s been thrown out of her college dorm for drinking and is almost as prickly as her uncle. Nicky is being eaten alive by multiple stressors. He has poured all his money into a high-toned bar that his father has never deigned to visit. And he feels that he alone bears the responsibility for his mother’s well-being. He’s furious that Bert won’t put her in a facility for people with dementia, even after she has wandered into the snow in a nightgown and boarded a train. Bert is a stubborn cuss.

“Actually, ‘cuss’ is the exact wrong word. A devout Catholic, Bert abhors his kids’ swearing and believes it’s his duty is to care for his wife until the bitter end. Also, he adores her. The subtext (and Über-text) of What They Had is the impact of such an overbearing father on his children’s self-esteem. Bert compelled (impelled, bullied) Bridget to marry an up-and-comer she didn’t love and now can barely stand. (Seen very briefly and played by Josh Lucas, the husband seems a nice enough fellow but dull.) Bert also insists on belittling Nicky — a bar owner — by calling him a bartender. The crux of Nicky and Bridget’s arguments is that she has power of attorney over her parents but won’t stand up to them. Nicky hectors her, she squirms, Nicky hectors her, she squirms, and nothing happens.

“Because nothing happens for a while doesn’t mean What They Had droops. Swank manages the difficult task of looking powerfully indecisive — i.e., animating her inaction, making you feel her inner struggle. Shannon I can’t begin to praise enough. Only last week, in a review of the war movie 12 Strong, I said he remains on pace to act in more movies than anyone ever while also doing plays, and here he is again and as good as I’ve seen him. (A tall order: He was, believe it or not, a definitive Dr. Astrov in an intimate theater production of Uncle Vanya a few years back.) His Nicky is primed to jump at his family’s criticisms, which means he seizes on those times when he can criticize back. Nicky is often hilariously rude and often just rude.

“Blythe Danner has the difficult task of responding to everything and registering almost nothing. She does it beautifully, with lyricism. Perhaps there’s something romanticized about her — forgive me — blitheness. I don’t know, not having observed enough people with Alzheimer’s. I do know that the way in which she switches on a dime from a nurturing mother (greeting every new person with ‘There’s my baby!’) to a little girl who wants to go home is heartbreaking. Forster, meanwhile, anchors the movie. Without yelling, his Bert has a bullying power — the kind that comes from utter faith in his own rationality (not to mention the Catholic Church).

“Chomko — a one-time actress and playwright — went through something similar with her own grandparents, to whom the film is dedicated. (They appear in a photograph, of course.) She does something in What They Had that I’ve never seen in this kind of film: The family laughs at some of Ruth’s screwball-illogical interjections. This didn’t offend me in the least: Laughter is a coping device, and Ruth — being largely oblivious — laughs with everyone else. Those moments are always double-edged, though. There’s a wonderful bit when Nicky solemnly informs Bridget that his mother hit on him and they both go into hysterics. But later, as the film inches towards its climax, Nicky tells that to his dad, and it’s the first time we see Bert speechless, unable to process what he’s hearing. There’s raw power in Chomko’s writing, but so much scrupulousness and craft that you feel safe when the time comes to weep.”

OCTOBER 26 (streaming on Netflix): Been So Long (dir. Tinge Krishnan) (DP: Catherine Derry) – Screen Daily’s London Film Festival review by Nikki Baughan: “Seven years after her debut film Junkhearts screened at the London Film Festival, director Tinge Krishnan returns with Been So Long, set to bow on Netflix on October 26 but screening first as a Special Presentation at the same festival. Fortunately, this vibrant musical love story is a rather more upbeat prospect than her first work. As established in the colourful opening musical number, in which the historic markets of Camden are transformed into a joyous streetdance, Che Walker’s adaptation of his own 1998 play — reimagined as a stage musical in in 2009 — seems to paint London as a town of optimistic possibility. That, together with the rising star power of Michaela Coel (Channel 4’s ‘Chewing Gum’), should pull in numbers for the SVOD giant.

“On the surface, this is a fairly standard love-conquers-all narrative, complete with familiar beats; the excitement of initial chemistry gives way to doubts, mistakes are made, decisions are hard-fought and, eventually, fate finds its way. Been So Long is, however, given additional texture thanks to its black female focus. Working from Walker’s astute screenplay, Coel is excellent as determined single mother Simone, unwilling to admit her vulnerabilities – her desire to protect her disabled daughter both admirable and an obvious smokescreen for her own fears. Ronke Adekoluejo is a particular standout as her brash best friend Yvonne, a fiercely proud woman entirely in control of her own sexual identity, whose character arc also calls for some genuinely moving soul searching of her own.

“Simone has worked hard to create a safe bubble for herself and her young girl — ‘It’s me and you against the world’ is her constant refrain — but when she meets Raymond (Arinze Kene), recently out of prison and working to get back on his feet, their instant connection is like an emotional wrecking ball. While Yvonne encourages her to spread her wings — ‘Your vagina called me, and told me it’s dying,’ she admonishes — Simone finds herself locked in a battle between past mistakes and future happiness.

“Indeed, the entire cast, which also features George MacKay as a troubled young addict, shoulders the story with energy and personality; no mean feat when it also requires them to belt out Arthur Darvill’s original songs (rearranged for the screen by music producer and score composer Christopher Nicholas Bangs) and carry out some intricate choreography. While all are confidently handled by Krishnan, some of these moments work better than others — Yvonne’s ‘I Want A Fella’ is a raucous, feminist highlight, while Raymond’s bar seduction song is, perhaps intentionally, rather more awkward.

“Crucially, underneath the music and the soft-focus romance Been So Long makes some poignant observations about community, family and the importance of connection. Most obviously, that plays out in Simone’s personal experiences; that her own father left her mother, and her daughter’s father also walked out, has clearly shaped the cautious, independent woman she is today. It’s also important that, even as she falls in love with Raymond, it’s Simone’s relationship with her daughter and Yvonne that are the strongest in the film, and the ones she works hardest to maintain.

“In a wider sense, Been So Long also highlights how traditional social structures are being eroded. ‘People don’t want inclusivity, they want exclusivity,’ says the owner of a new local bar and, as cinematographer Catherine Derry lingers on the fading facades and shuttered buildings of Camden, it’s a reminder of how gentrification is redrawing the lines of community there. But, as her camera drinks in the stunning London skyline, or vivid sequences of people from all walks of life dancing in unison, it’s also clear that the film’s message is rather more optimistic. If we’re open to new experiences, and new people, we can still find our place.”

OCTOBER 26: The Long Shadow (dir. Frances Causey with co-dir. Maureen Gosling) – Synopsis from the film’s official website: “Of all the divisions in America, none is as insidious and destructive as racism. In this powerful documentary, the filmmakers, both privileged daughters of the South, who were haunted by their families slave owning pasts, passionately seek the hidden truth and the untold stories of how America—guided by the South’s powerful political influence—steadily, deliberately and at times secretly, established white privilege in our institutions, laws, culture and economy.

“William Faulkner once said, ‘The past is never dead. The past is not even past.’ And this echoes one scholar’s warning in the film: ‘We’re still fighting the Civil War, and the South is winning.’ Anti-black racism has survived like ‘an infection,’ rigging the game against African-Americans and denying them full access to the American dream.

“By telling individual stories—of free, enterprising blacks in Canada; of a modern, racially motivated shooting—the filmmakers movingly personalize the costs and the stakes of our continued inaction. The Long Shadow presents a startling, unrecognized history that provides much needed context when considering the major issues impacting black/white relations in the United States today.

“Finally, The Long Shadow is a masterful film that captures the disturbing story of the enduring human cost of prejudice and ignorance in the US that continues to cast a long shadow over our national identity and values and ultimately, our celebrated democracy.”

OCTOBER 26 (in theaters & streaming on Netflix): Shirkers (dir. Sandi Tan) (DP: Iris Ng) – IndieWire’s Sundance Film Festival review by Eric Kohn: “Shirkers is a documentary about the production of an uncompleted movie, but it doubles as an upgraded version of the missing project itself. As a punk teen in early-nineties Singapore, Sandi Tan wrote a feminist slasher movie for the ages, an exploitation road movie designed to ruminate on the energy of youth, creativity, and alienation. The director, a much older American high school instructor with dubious motives, stole the film canisters for unknown reasons and vanished into the mist; two decades later, Tan has completed a fascinating personal look at her quest to uncover his motives, resurrecting the significance of her original intentions in the process.

“Tan’s actual debut, Shirkers takes its title from her earlier effort, an adorably deranged slasher movie in which she starred as a bored young woman killing men to pass the time. Though her old pals celebrate its relevance to Singapore’s minuscule film community at the time, Tan — whose voiceover, hand-scrawled credits and substantial archival materials guide the narrative — sees it more as representative of her artistic awakening. As her older mentor’s greed and envy leads to tragic circumstances, Shirkers becomes a paean to the pivotal moment when the idealism of young adulthood faces a harsh reality check.

“With her best pals Jasmine Ng (later a filmmaker in her own right with 1999’s Eating Air) and Sophie Siddique, both of whom appear in Shirkers as their adult selves, Tan found an outlet from her drab surroundings through the subversive discoveries of loud music, Jim Jarmusch movies and underground zines. With a wondrous score underlining this dynamic period in her life, Tan reflects on what it meant to live on a small island nation and uncover the prospects of escapism through storytelling: ‘I had the idea that you found freedom with worlds inside your head.’

“Enter Georges Cardona, an assertive fortysomething who takes an interest in fostering his students’ enthusiasm for film history, even as his tactics seem questionable in retrospect. Far more than a classroom instructive, Cardona takes Sandi and her friends around for late-night drives, as old VHS footage documents their joy rides through empty roads as if they’ve broken into the set of Trash Humpers. Cardona may be crossing boundaries with his students, but they’re just thrilled to break all the rules.

“At first, he’s Tan’s key to realizing the creative utopia in her head, as the pair travels America together before she starts college in London. Then she writes the screenplay for Shirkers, and Cardona gives her the confidence to bring it to life. The production becomes a communal affair, but Cardona lords over it with a destructive air that only worsens as time goes on; he seems to consciously slow the production’s progress before stealing the end result, presumably obstructing Tan’s success as a twisted means of spreading his own failures to feel less alone in the world.

“Shirkers didn’t vanish forever because its footage becomes the backbone of Tan’s documentary. The filmmaker finally scored the footage decades later, and in the process, learned more about Cardona’s deranged track record. The root of his motives is ultimately less revelatory than the way the movie uses it to explore the fragile nature of artistic desire and what can happen when it’s left unsatisfied. Cardona may have succeeded at spreading his malady, but Tan’s innovative diaristic project means that she gets the last word.

“Shirkers has the handmade delicacy of a scrapbook come to life, blending ample footage from the original production with candid modern-day interviews and photography. Equal parts travelogue and archival rescue mission, the ensuing drama becomes a microcosm of broader themes. While the interest surrounding Tan’s project speaks to the limited field of Singapore’s film industry, her initial passion as a young cinephile reflects the state of a country capable of absorbing Western culture without cementing a cultural revolution of its own.

“Having established such potent themes and an intriguing central mystery, Shirkers falls short of a satisfying solution by its final third. Tan seems hesitant to reach firm answers about Cardona’s story, or the root of his obsession with her in the first place. Fortunately, those questions mainly serve as a conduit to discussions about her passion for the project.

“Whether it was a botched masterpiece or simply an idealistic young woman’s first stab at finding her creative voice, Tan can’t say. After shifting careers from production to criticism before finding her way back again, she has produced a remarkable statement on the formation of a creative identity across many years and life experiences. Whatever the original intentions of Shirkers, some two decades years later, she found out a way to complete it on her own terms.”

OCTOBER 26: Viper Club (dir. Maryam Keshavarz) – The Landmark at 57 West synopsis: “ER nurse Helen Sterling (Susan Sarandon) struggles to free her grown son, a journalist captured by terrorists in the Middle East. After hitting walls with the FBI and State agencies, she discovers a clandestine community of journalists, advocates, and philanthropists who might be able to help. Co-starring Matt Bomer, Lola Kirke, Julian Morris, Sheila Vand, Adepero Oduye and Edie Falco. Directed and co-written by Maryam Keshavarz (Circumstance).”

OCTOBER 26: Weed the People (dir. Abby Epstein) (DPs: Paulo Netto, Richard Pearce and Jenna Rosher) – Film Journal International review by Gary M. Kramer: “Weed the People is director Abby Epstein’s effective exploration into the way cannabis oil is being used as an alternative medicine for kids battling cancer. The film introduces several patients, from Sophie Ryan, a baby with a brain tumor, to AJ Kephart, a teenager with stage 4 bone cancer, to show how they are responding to doses of cannabis oil—often in conjunction with chemotherapy. The results, as the film shows, are nothing short of miraculous.

“The stories are all heartfelt. Epstein wants Weed the People to provide folks with hope. It may jerk tears when one subject encounters a setback, or another patient loses their battle with cancer, but there will also be tears of joy with the film’s multiple success stories.

“A significant part of the documentary is devoted to questioning the dearth of research for medical marijuana in the U.S. and the government’s lack of support for the viability of cannabis oil’s medicinal properties. (The DEA declined loosening restrictions on medical marijuana.) Because marijuana is classified as a Schedule I drug, it is not tested for its healing properties—despite its use a century ago, before weed was criminalized. Moreover, scientists in Israel and Spain are making great progress in showing how cannabis is killing cancer cells. THC is shown for reducing tumor growth and metasticization.

“As such, individuals who believe in the healing properties of marijuana are on the front lines of this battle, and Weed the People showcases the important and groundbreaking work they are doing in the field. Dr. Bonni Goldstein, a cannabis physician, counsels patients and provides support for families like the Petersons, who have to move from Chicago to California to be eligible for medical marijuana.

“Likewise, Mara Gordon, co-founder of Aunt Zelda’s Oil, creates THC and CBD oils that are given to her patients to kill cancer cells in exchange for collecting their data (to determine efficacy). Her efforts are altruistic; she makes her oils in her kitchen, and charges families for the source plant but absorbs her overhead costs. Mara claims she doesn’t have medical training, but she does have experience, and her skills and care provide invaluable support for her patients and their families. Weed the People generates some drama when Tracy, the mother of a patient Mara is treating, becomes a ‘momcologist,’ and starts her product line, CannaKids. Tracy stopped using Mara’s more expensive products and used the knowledge she gained from working with Mara to her own ends.

“The ethical, legal and financial aspects of this burgeoning industry are indirectly addressed by Epstein’s film. There are some discussions of the expense, and Jim von Harz raises money through a fund to help supply cannabis oil for his daughter’s ongoing treatment. One mom, Angela Smith, is given an oil that is determined to contain rubbing alcohol, suggesting that there are hucksters out there offering faulty products. Moreover, when the Peterson family return to Chicago, ‘angel donors’ illegally send cannabis shipments to continue their son’s treatment. These are all fascinating if underexplored topics that could easily support another film on the subject of medical marijuana.

“But the broad approach and focus on the families and practitioners here is not a major drawback. Although Weed the People is one-sided—in that it does not give a voice to opponents of medical marijuana—this seems like a deliberate decision. Epstein is using the impassioned testimonies of parents to makes the film’s salient points.

“Several parents saw cannabis oil therapy as a last resort—because they were willing to try anything to save their children. In doing so, they become the treatment’s greatest advocates. As mothers like Tracy and Angela are amazed by the noticeable changes in their kids’ health, viewers, too, cannot help but be moved by the good news they receive and the support they get from their kids’ oncologists. It is gratifying to see footage of Angela’s son Chico, who suffers from a soft tissue cancer called rhabdomyosarcoma, lying listlessly on the couch in early scenes riding a bike by the film’s end. When Chico wants to get a grow kit for his 14th birthday, it is both provocative and oddly satisfying.

“Weed the People makes a convincing case for the progress and advances most of the kids profiled here experience. The film wears its bias proudly, as it wants to foment change and save lives. That message comes across clearly here, even if some folks may remain skeptical.”