How does one make a follow-up to a masterpiece? In 1993, Wim Wenders directed Faraway, So Close!, a companion film to his earlier tour de force Wings of Desire (1987). The first film followed two angels, Damiel (Bruno Ganz) and Cassiel (Otto Sander), the former giving up his immortality to become human. Faraway follows Cassiel’s story as he too transitions into mortal existence. In a continuation of an important element from Wings, Cassiel often observes Berlin from atop the Victory Column (seen above), which makes for a really amazing opening to the film as the camera circles the statue high up in the sky.

Wenders rights a wrong from the previous film by featuring a female angel in a significant role (there had been some angel-women in Wings, but they ended up being cut from the final film). Nastassja Kinski, who had previously worked with Wenders in The Wrong Move (1975) and more famously in Paris, Texas (1984), plays Cassiel’s associate, Raphaela. Kinski’s performance is good, but she is not given much screen time.

Willem Dafoe has a flashy supporting role that I enjoyed, although I understand that some viewers find him distracting – not necessarily because of his American-ness, but maybe because of his innate Willem-Dafoe-ness. I don’t want to give away the identity of his character, but it’s an entertaining performance by one of cinema’s weirdest artists.

Speaking of high-quality acting, I want to stress that Faraway is especially worth seeing for those who are fans of Otto Sander (seen above with Wenders on the set) and wished he had had more to do in Wings. It’s great to see Sander in a leading role, although ultimately the narrative does not reach the stunning heights of its predecessor. Where Wings was poetic, Faraway is more conventional and has the kinds of conflicts you might see in a more typical film’s screenplay.

Sander is terrific at demonstrating Cassiel’s unbearable melancholy at realizing all the saddest aspects of human life, such as being unable to overhear other people’s thoughts (which he could do as an angel) and having to deal with violence and pain.

Bruno Ganz and Solveig Dommartin return as Damiel and Marion. Dommartin is particularly good here since seems less idealized than in Wings of Desire and more “real,” possibly because she was six years older and the character is now a wife and mother, as well as working as a bartender to supplement the family’s income.

The famed German actor Heinz Rühmann, then in his early 90s, made his final film appearance in Faraway, doing his best work in his scenes with Sander. I wish I could also find images from the film of the great Horst Buchholz, Rüdiger Vogler (a perennial favorite of Wenders since the early 1970s) and Monika Hansen (she was married to Otto Sander in real life) since they are memorable actors in Faraway too.

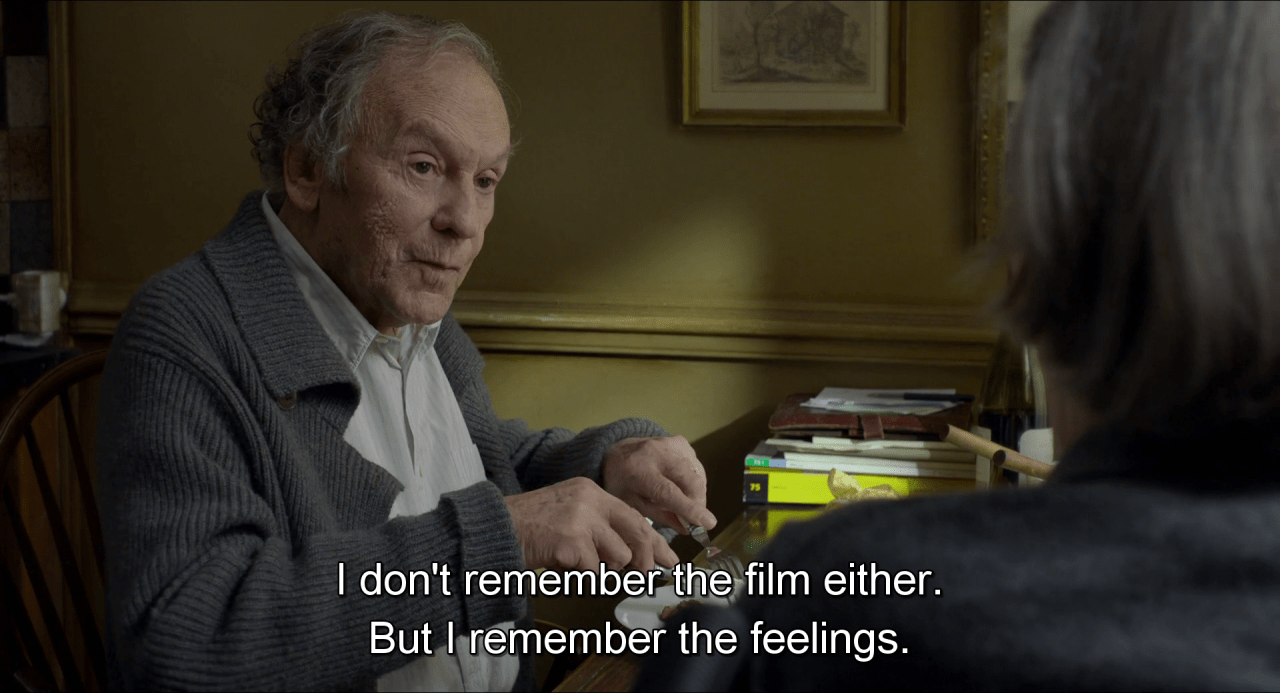

Lou Reed shows up, a sensical choice given that he had an album named Berlin in 1973. He provides Faraway with its one concert scene, performing a song called “Why Can’t I Be Good?” which provides Cassiel with important questions to ask himself (like the song’s title). I don’t think that the concert segment is even a fraction as powerful as either of the concert scenes from Wings of Desire, but the earlier scene (seen above) where Reed tries to remember some lyrics is a nice, poignant moment that combines a love of music (and musicians) with an awareness of aging/the passage of time.

…Reed even gets some extra screen time, appearing in a scene that takes place after Cassiel has become mortal.

Of course Peter Falk appears in Faraway too, just as he did in Wings, dispensing wisdom and aiding his ex-angel friends when they need him. After all, if anyone can help in a jam, it’s Columbo. Perhaps a bit of the charm is gone, but Falk is always a fun actor to watch. He has a kind of instant likeability.

Perhaps my favorite scene is when Cassiel tries out the trapeze, remembering the sensations of flying from when he was an angel. Even though the film is ultimately a little too long and the plot does not entirely make sense, it is worth seeing for moments like this. Sometimes with film that’s enough.

Postscript: the soundtrack has some excellent songs, my favorite being “Stay (Faraway, So Close!)” by U2. Wim Wenders directed the music video for the band and you can see many elements taken directly from the two films.