Cinema Journal (Vol. 10, No. 2 (Spring 1971)) review by Howard Suber of the collection The New York Times Film Reviews, 1913-1968 (published in six volumes, 1970).

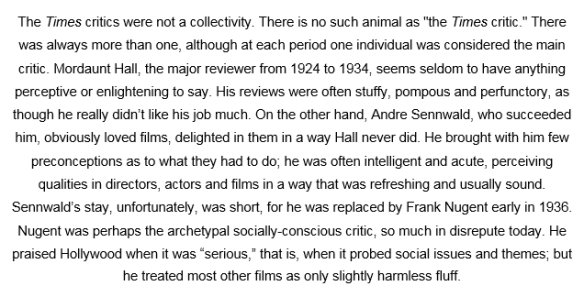

I am writing today about Andre David Sennwald, Jr. (born August 4, 1907; died January 12, 1936). He was the second person to hold the position of chief film critic (1935-1936) at the New York Times, the first being Mordaunt Hall (1924-1934) and the third being Frank S. Nugent (1936-1940). Although Sennwald wrote during one of the most important periods in film history – Pre-Code talkies (1931-1934), then the transition to the implementation of the Motion Picture Production Code (1934-1936), including Becky Sharp as the first-ever three-strip-Technicolor feature – his name is a footnote in the New York Times’ history of film criticism.

There isn’t really any way for me to know Andre Sennwald outside of what he wrote for the New York Times, although I would like to particularly since he and I share the same birthday. He adored W.C. Fields and Greta Garbo; he had a definite disdain for John Boles; he sometimes rolled his eyes at the popularity of Shirley Temple; he wasn’t always sure what to make of James Cagney’s cinematic choices, depending on which film he had to review (in the earliest Sennwald piece that I have found, dating to April 1931, the first sentence of his negative critique of The Public Enemy describes it as “just another gangster film at the Strand, weaker than most in its story, stronger than most in its acting, and, like most, maintaining a certain level of interest through the last burst of machine-gun fire”); after watching Captain Blood (1935), he saw the obvious potential for superstardom in “spirited and criminally good-looking” Errol Flynn; in perhaps my favorite bit of flattery, Sennwald wrote in a review of The Gilded Lily (1935) that “there is a young man named Fred MacMurray who can munch a peanut or take off his shoes like one of the boys” and that “Mr. MacMurray’s ability to seem completely natural without abandoning his charm ought to make him one of the most popular of the cinema’s glamour men within the next few months.”

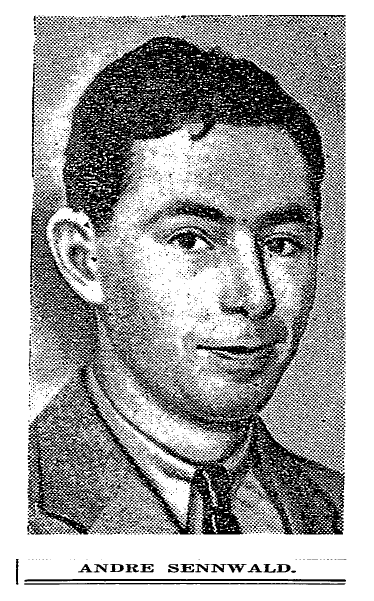

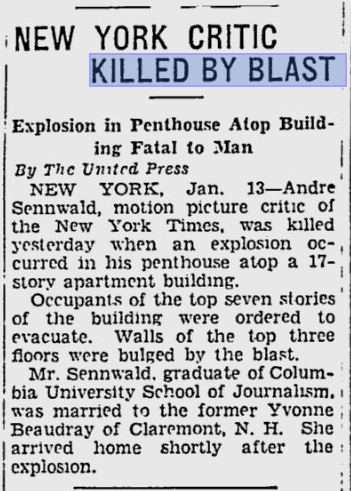

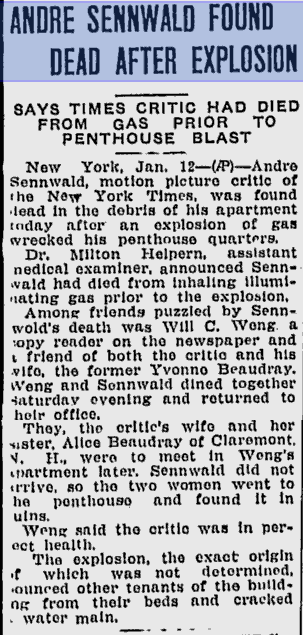

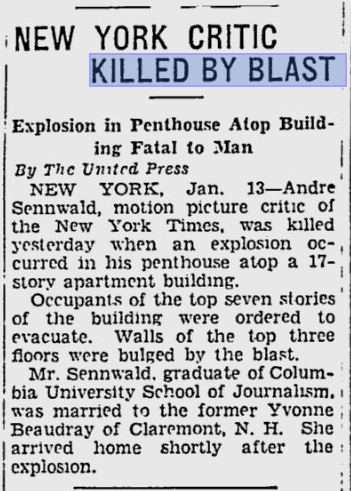

Andre Sennwald’s career was all too brief. Here is some of the news coverage of his death in 1936.

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 1/13/36

The Pittsburgh Press, 1/13/36

Lewiston Daily Sun, 1/13/36

Motion Picture Daily, 1/13/1936

Columbia Daily Spectator, 1/16/36

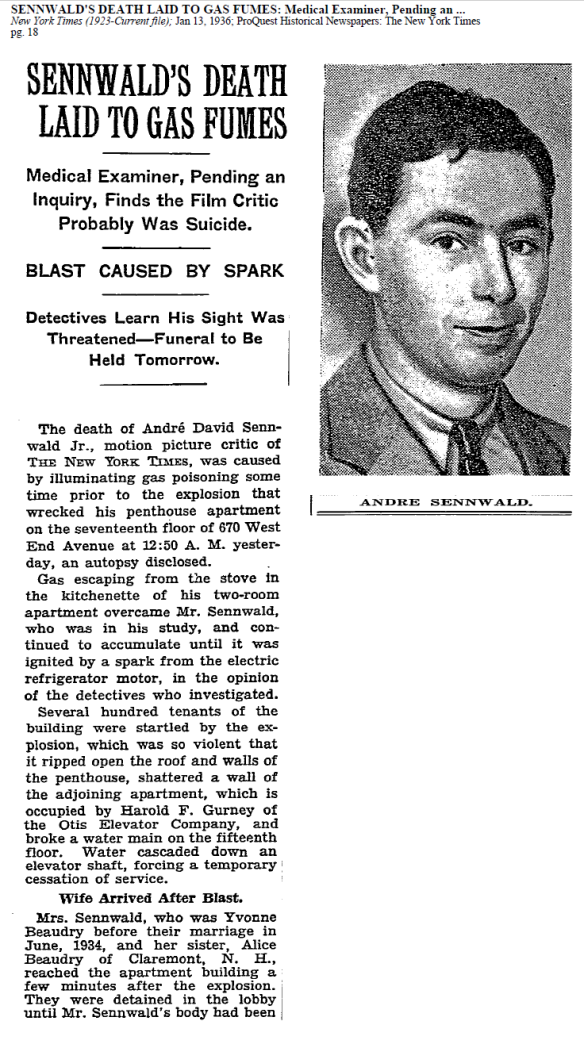

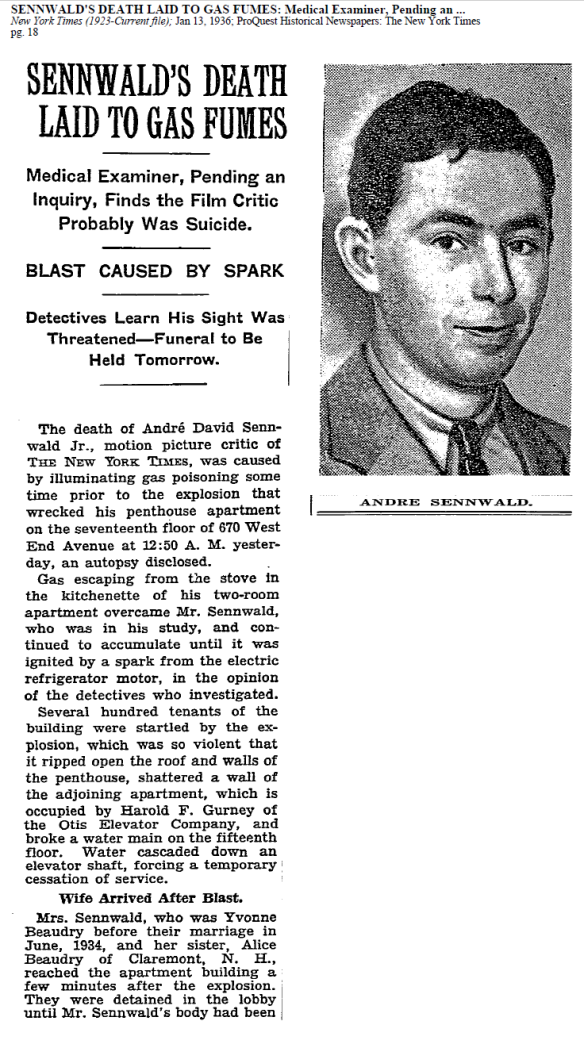

An article published in the Times Herald of Olean, New York on January 13 mentions that the explosion “was caused by escaping gas in the kitchen” and that “it was believed to have been set off by a spark from an electric refrigerator,” while the January 14 copy of Jefferson City, Missouri’s Daily Capital News states: “A medical examiner’s report indicated today that Andre David Sennwald, Jr., movie critic of the New York Times, died by his own hand. An explosion wracked Sennwald’s penthouse early yesterday. The top three floors of the apartment house were damaged and a broken water main sent water down elevator shafts, disrupting service. The explosion was caused by escaping gas. The medical examiner found that Sennwald died from gas poisoning, showing he was dead before the explosion. He had suffered from an eye disease and was said to have feared for his sight.” The mystery remains unanswered: did Andre Sennwald mean to commit suicide because of supposedly impending blindness, or was the gas leak/explosion a terrible accident?

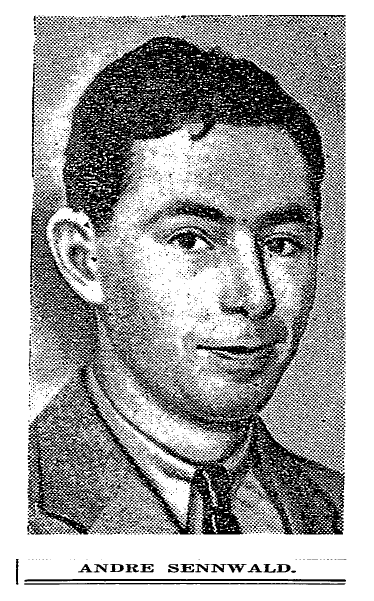

Here is a New York Times article from January 13 that shows the photo of Sennwald that I embedded earlier in the post:

Despite the medical examiner’s findings, unless there was a suicide note that the family withheld or other information which the investigating police did not make available to the public – or which is simply not searchable through free Google fieldwork – it seems to me that it is impossible to know with 100% certainty the intention (or lack thereof) that led to the death of Sennwald, who had been considered “the brightest film critic” in New York City (according to The Montreal Gazette), at age twenty-eight.

Columbia Daily Spectator, 1/13/36

Andre David Sennwald is buried at Ferncliff Cemetery in Hartsdale, NY (according to Find a Grave). Occasionally his name resurfaces, although such acknowledgments are rare. In 2014, J. Hoberman wrote a New York Times essay about classic Universal Studios horror films and he quoted Andre Sennwald’s musings on the role of violence in American film: “In the mad, confused days which preceded our entrance into the World War, the cinema was satiating the blood lust of noncombatant Americans with just such vicarious stimulants. Hollywood, always quick to reflect or stimulate a mass appetite, seems to be doing the same thing all over again.” More recently, New York Post film critic Lou Lumenick wrote a Tweet this past January to commemorate the eightieth anniversary of Sennwald’s death. In memory of this sadly overlooked critic, here are a dozen of my favorite examples of Andre Sennwald’s New York Times film reviews:

Sons of the Desert (1933, dir. William A. Seiter) – reviewed January 12, 1934

“Let it be said at once that the new Laurel and Hardy enterprise has achieved feature length without benefit of the usual distressing formulae of padding and stretching. It is funny all the way through. The mournful and witless Mr. Laurel and the frustrated Mr. Hardy are just as unfitted for the grim realities as they have ever been. A Quixote and Panza in a nightmare world, where even the act of opening a door is filled with hideous perils, they fumble and stumble in their heartiest manner. At the Rialto spectators are checking their dignity with the doorman; an audience yesterday spluttered, howled and sighed in sweet surrender.”

The Old Fashioned Way (1934, dir. William Beaudine) – reviewed July 14, 1934

“To the lyric popping of vest buttons and the tortured noises of the laugh that begins deep down, the magnificent Mr. Fields has graciously placed himself on view at the Paramount, and honest guffaws are once more heard on Forty-third Street. The great man, the omnipotent oom of one of the screen’s most devoted cults, brings with him some new treasures, as well as a somewhat alarming collection of wheezes which, ten years ago in the vaudeville tank towns, must have seemed not long for this world. But somehow when Mr. Fields, in his necessary search for comic business, is forced to strike up a nodding acquaintance with vintage gags, they seem to become almost young again.”

Our Daily Bread (1934, dir. King Vidor) – reviewed October 3, 1934

“King Vidor, who gave us ‘The Crowd’ and ‘Hallelujah,’ has plunged his camera boldly into vital American materials in ‘Our Daily Bread,’ which opened at the Rialto last night. His new work, which he wrote, produced and financed himself, is a brilliant declaration of faith in the importance of the cinema as a social instrument. In richness of conception alone, Mr. Vidor’s attempt to dramatize the history of a subsistence farm for hungry and desperate men from the cities of America would deserve the attention and encouragement of intelligent film-goers. But ‘Our Daily Bread’ is much more than an idea. Standing in the first rank of American film directors, Mr. Vidor has brought the full power of a fine technique and imagination to his theme. ‘Our Daily Bread’ dips into profound and basic problems of our everyday life for its drama, and it emerges as a social document of amazing vitality and emotional impact.

“The effect of the photoplay is to bring the cinema squarely into the modern stream of socially-minded art and to lay bare for the inquisitive cameras the same fundamental dramatie [sic] themes which the young proletarian novelists like Albert Halper, Robert Cantwell and William Rollins are exploiting in the new American literature. For that reason alone it is impossible to over-estimate the significance of the new work.

“You may quarrel with the sentimental idealism of the ex-convict who voluntarily surrenders himself to the authorities so that his fellows may obtain the reward and save the crops from the drought. This theme, incidentally, was suggested to Mr. Vidor by Charlie Chaplin. You may quarrel with the theme of the blond-headed siren who almost wrecks the collectivist farm in her gratuitous efforts to lure the leader to destruction. This department applauds the Chaplinesque note and deplores the Theda Barish element. But ‘Our Daily Bread’ is too important as a canvas to be chastised for its debatable taste in minor details of Mr. Vidor’s brushwork.”

The Painted Veil (1934, dir. Richard Boleslawski) – reviewed December 7, 1934

“Pettish folk, out of an evident spirit of wish-fulfillment, are forever discovering that Greta Garbo has outlived her fame. They are knaves and blackguards and they should be pilloried in the middle of Times Square. She continues handsomely to be the world’s greatest cinema actress in the Oriental triangle drama, ‘The Painted Veil,’ which begins an engagement at the Capitol this morning. Tracing its ancestry to Somerset Maugham’s novel, which it resembles only in the casual surface qualities of the narrative, Miss Garbo’s new film is a conventional, hard-working passion-film which manages to be both expert in its manufacture and insincere in its emotions. Since it allows Miss Garbo to triumph once more over the emotional rubber-stamps that the studios arrange for her, we must not be ungenerous about ‘The Painted Veil,’ Richard Boleslawski has made a visual treat of it, and Herbert Marshall and George Brent head an excellent group of subsidiary players.

“It is the height of dishwater diplomacy to affect a temperate attitude toward this cool and lovely lady with the sad, white face and the throaty voice. She is the most miraculous blend of personality and sheer dramatic talent that the screen has ever known and her presence in ‘The Painted Veil’ immediately makes it one of the season’s cinema events. Watch her stalking about with long and nervous steps, her shoulders bent and her body awkward with grief, while she waits to be told if her husband will die from the coolie’s dagger thrust. It is as if all this had never been done before. Watch the veiled terror in her face as she sits at dinner with her husband, not knowing if he is aware of her infidelity; or her superb gallantry when she informs him of what it was that drove her into the arms of his friend; or her restlessness on the bamboo porch in Mei-Tan-Fu with the tinny phonograph, the heat and her conscience. She shrouds all this with dignity, making it precious and memorable.”

Becky Sharp (1935, dir. Rouben Mamoulian) – reviewed June 14, 1935 (reproduced here in its entirety since this particular movie is so important in film history)

“Science and art, the handmaidens of the cinema, have joined hands to endow the screen with a miraculous new element in ‘Becky Sharp,’ the first full-length photoplay produced in the three-component color process of Technicolor. Presented at the Radio City Music Hall yesterday for its first public showing, it was both incredibly disappointing and incredibly thrilling. Although its faults are too numerous to earn it distinction as a screen drama, it produces in the spectator all the excitement of standing upon a peak in Darien and glimpsing a strange, beautiful and unexpected new world. As an experiment, it is a momentous event, and it may be that in a few years it will be regarded as the equal in historical importance of the first crude and wretched talking pictures. Although it is dramatically tedious, it is a gallant and distinguished outpost in an almost uncharted domain, and it probably is the most significant event of the 1935 cinema.

“Certainly the photoplay, coloristically speaking, is the most successful that has ever reached the screen. Vastly improved over the gaudy two-color process of four and five years ago, it possesses an extraordinary variety of tints, ranging from placid and lovely grays to hues which are vibrant with warmth and richness. This is not the coloration of natural life, but a vividly pigmented dream world of the artistic imagination.

“Rouben Mamoulian and Robert Edmond Jones have employed the new process in a deliberately stylized form, so that ‘Becky Sharp’ becomes an animate procession of cunningly designed canvases. Some of the color combinations make excessive demands upon the eye. Many of them are as soothing as black and white. The most glaring technical fault, and it is a comparatively minor one, is the poor definition in the long shots, which convert faces into blurred masses. In close-ups where scarlet is the dominant motif, there is also a tendency to provoke an after-image when the scene shifts abruptly to a quieter color combination.

“The major problem, from the spectator’s point of view, is the necessity for accustoming the eye to this new screen element in much the same way that we were obliged to accustom the ear to the first talkies. The psychological problem is to reduce this new and spectacular element to a position, in relation to the film as a whole, where color will impinge no more violently upon the basic photographic image than sound does today. This is chiefly a question of time and usage. At the moment it is impossible to view ‘Becky Sharp’ without crowding the imagination so completely with color that the photoplay as a whole is almost meaningless. That is partly the fault of the production and partly the inevitable consequence of a phenomenon. We shall know more about the future of color when its sponsors employ it in a better screen play than ‘Becky Sharp.’

“The real secret of the film resides not in the general feeling of dissatisfaction which the spectator suffers when he leaves the Music Hall, but in the active excitement which he experiences during its scenes. It is important and even necessary to judge the work in terms of its best—not its worst or even its average. ‘Becky Sharp’ becomes prophetically significant, for example, in the magnificent color-dramatization of the British ball in Brussels on the eve of Waterloo.

“Here the Messrs, Mamoulian and Jones have accomplished the miracle of using color as a constructive dramatic device, of using it for such peculiarly original emotional effects that it would be almost impossible to visualize the same scene in conventional black and white. From the pastel serenity of the opening scenes at the ball, the color deepens into somber hues as the rumble of Napoleon’s cannon is heard in the ballroom. Thenceforward it mounts in excitement as pandemonium seizes the dancers, until at last the blues, greens and scarlets of the running officers have become an active contributing factor in the overwhelming climax of sound and photography.

“If this review seems completely out of focus, it is because the film is so much more significant as an experiment in the advanced use of color than as a straightforward dramatic entertainment. Based upon Langdon Mitchell’s old dramatization of ‘Vanity Fair,’ it is gravely defective. Ordinarily Mr. Mamoulian is a master of filmic mobility, but here his experimental preoccupation with color becomes an obstacle to his usual fluid style of screen narration. Thus a great deal of ‘Becky Sharp’ seems static and land-locked, an unvarying procession of long shots, medium shots and close-ups. It is endlessly talkative, as well, which is equally a departure from Mr. Mamoulian’s ordinary style.

“Perhaps it was inevitable that Thackeray’s classic tale of the ambitious Becky and her spangled career in English society would be reduced on the screen to a halting and episodic narrative. But the film is unconscionably jerky in its development and achieves only a minor success in capturing the spirit of the original. In many of the screened episodes, Thackeray’s satirical portraits come perilously close to burlesque, and they barge over the line in several places. Miriam Hopkins is an indifferently successful Becky, who shares some excellent scenes with many others in which she is strident and even nerve-racking. Frances Dee makes an effective Amelia, and photographs beautifully in addition. There are fine performances in the celebrated rôles by Sir Cedric Hardwicke, Alison Skipworth, Nigel Bruce and Alan Mowbray.

“But one thing is certain about ‘Becky Sharp.’ Its best is so good that it becomes a prophecy of the future of color on the screen. It forced this column to the conclusion that color will become an integral motion picture element in the next few years. If Mr. Mamoulian and Pioneer Pictures can be persuaded to film a modern story for their next venture, striving to repress their use of color to the more sombre hues of our twentieth century civilization, ‘Becky Sharp’ will have fulfilled its great promise.”

No More Ladies (1935, dir. Edward H. Griffith) – reviewed June 22, 1935

“The kind of class which Eadie (who was a lady) used to spell with a capital K has been expensively buttered on the motion picture version of ‘No More Ladies,’ which opened at the Capitol Theatre yesterday. Joan Crawford has it, Robert Montgomery has it, the dialogue has it, Adrian’s gowns have it, and the opulent Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer sets have it. The photoplay, despite its stage ancestry, is out of the same glamour factory as Miss Crawford’s ‘Forsaking All Others.’ If it is less furiously arch than that modern classic of sledgehammer whimsey [sic], it is also somewhat less successful as entertainment. Out of the labors of the brigade of writers who tinkered with the screen play, there remain a sprinkling of nifties which make for moments of hilarity in an expanse of tedium and fake sophistication.

“…Although Donald Ogden Stewart has contributed several really funny lines, the screen play is chiefly notable for its surface shimmer, the hollowness of its wit and the insincerity of its emotions. The sophistication of ‘No More Ladies’ is the desperate pretense of the small girl who smears her mouth with lipstick and puts on sister’s evening gown when the family is away. It ought to make a very respectable profit.”

Curly Top (1935, dir. Irving Cummings) – reviewed August 2, 1935

“Shirley Temple’s new picture is dedicated to the simple things of life, with special reference to the power of the hello-neighbor smile in conquering the ills of humanity. So shameless is it in its optimism, so grimly determined to be cheerful, that it ought to cause an epidemic of axe murders and grandmother beatings in this sober vicinity. Shirley herself, far from showing signs of deterioration or overwork in ‘Curly Top,’ actually hints in her work at an increased maturity of technique. Her remarkable sense of timing has never been revealed more plainly than in the song and dance scenes in her new film, and she plays her straightforward dramatic scenes with the assurance and precision of a veteran actress. With all this, she has lost none of her native freshness and charm.”

Mad Love (1935, dir. Karl Freund) – reviewed August 5, 1935

“Peter Lorre, the brilliant Hungarian actor of ‘M,’ arranges another of his terrifying studies in morbid psychology in his first American photoplay at the Roxy. At heart ‘Mad Love’ is not much more than a super-Karloff melodrama, an interesting but pretty trivial adventure in Grand Guignol horror. With any of our conventional maniacs in the role of the deranged surgeon, the photoplay would frequently be dancing on the edge of burlesque. But Mr. Lorre, with his gift for supplementing a remarkable physical appearance with his acute perception of the mechanics of insanity, cuts deeply into the darkness of the morbid brain. It is an affirmation of his talent that he always holds his audience to a strict and terrible belief in his madness. He is one of the few actors in the world, for example, who can scream: ‘I have conquered science; why can’t I conquer love?’—and not seem just a trifle silly.

“Perhaps you have not yet made the acquaintance of Mr. Lorre: squat, moon-faced, with gross lips, serrated teeth and enormous round eyes which seem to hang out on his cheeks like eggs when he is gripped in his characteristic mood of wistful frustration. As if these striking natural endowments were not enough, his head has been shaved as clean as Mr. Micawber’s for the occasion, and his skull becomes an additional omen of evil in the morose shadows which Karl Freund has evoked for the photo-play.

“…‘Mad Love’ is frequently excellent when Mr. Lorre is being permitted to illuminate the dark and twisted recesses of Dr. Gogol’s brain. In the theatre des horreurs, which he attends night after night, you see him in his box watching his lady tortured upon the rack, veiling his eyes in an emotion which is both pain and sadistic joy as he listens to her screams. There is an extremely effective scene in which the doctor, going quite definitely mad, hears the voice of his subconscious lashing him for his failure to conquer the woman. In the climactic scene, when the doctor loses all contact with reality and immerses himself in his Pygmalion-Galatea identity, his maniacal laughter raises the hair on your scalp and freezes the imagination.

“Even if it is not quite what we might have looked for in Mr. Lorre’s first American picture, ‘Mad Love’ is an entertaining essay in the macabre, and it may be a useful vehicle for introducing him to his new American film public. As those fortunate filmgoers who saw him in ‘M’ do not need to be told, he is among the great screen actors. He is capably assisted here by Colin Clive as the injured pianist, May Beatty as the doctor’s drunken housekeeper, Keye Luke as his operating room assistant and Edward Brophy as the condemned murderer. Ted Healy, a highly amusing comedian, has gotten into the wrong picture.”

A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1935, dirs. William Dieterle and Max Reinhardt) – reviewed October 10, 1935

“Hollywood pursues the shapes and shadows of the unfettered imagination with courage, skill and heavy artillery in Max Reinhardt’s film version of ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream,’ which the Warner Brothers presented at the Hollywood Theatre last evening. Many of the elusive, dancing conceits of Shakespeare’s lyric fantasy remain at large, though, and seem to hover about the screen hooting derisively at the cinema’s determined bloodhounds. But Mr. Reinhardt has isolated some of the winged fancies and the photoplay caparisons them in rich and lovely stuffs. If this is no masterpiece, it is a brave, beautiful and interesting effort to subdue the most difficult of Shakespeare’s works, and it has magical moments when it comes all alive with what you feel when you read the play.

“For the work is rich in aspiration and the sum of its faults is dwarfed against the sheer bulk of the enterprise. It has its fun and its haunting beauty. The play has been adapted with intelligence and affection. Except for a laggard quality in the ballet movements, it moves with a mettlesome step. William Dieterle, one of the most skillful directors in Hollywood, has transferred Mr. Reinhardt’s visions to the screen all complete. Erich Wolfgang Korngold has arranged the Mendelssohn music in a magnificent score, which weaves a rhapsodic spell about the spectator and transports him to the sightless realm of Avon’s elves and fairies.

“But the plain and distressing truth is that the screen, in the proud act of releasing the play from the shackles imposed on it by the proscenium arch, has the embarrassing miracle to perform of creating visual images which will catch the phantoms that lurk behind the words. The Nijinska ballet, for example, evokes not the fairy attendants of Oberon and Titania, but pretty girls in white gauze and sturdy gentlemen with wings strapped to their shoulders.

“The goblins are dwarfs in make-believe masks and the moonbeams on which the fairies dance are clever mechanical tricks in which the man-made magic is never quite submerged in the illusion it is striving to create. If you look too eagerly at Puck as he soars into space on a stick, you will discover the wire on which he is being hoisted.

“It is an illuminating fact that the photoplay achieves perfection in the clowns, those pragmatic louts who have no belief in the revels of the fairy people in the enchanted wood between dusk and dawn. Joe E. Brown as Flute the Bellows-mender gives the best performance in the show. It is a privilege to roar with laughter when he is rehearsing for the rude masque or playing the timid Thisbe to James Cagney’s Pyramus. Hugh Herbert and Frank McHugh are uproarious as his fellow tradesmen.

“…Mickey Rooney’s remarkable performance as Puck is one of the major delights of the work. As the merry wanderer of the night, he is a mischievous and joyous sprite, a snub-nosed elf who laughs with shrill delight as the foolish mortals blunder through Oberon’s fairy domain. In the other important rôles the film is uneven in performance and suggests flaws in Mr. Reinhardt’s reading of the play. As Bottom, the lack-wit weaver whom Puck maliciously endows with an ass’s head, James Cagney is too dynamic an actor to play the torpid and obstinate dullard. While he is excellent in the scenes in the wood, in the ‘Pyramus and Thisbe’ masque he belabors the slapstick of his part beyond endurance.

“…It is difficult to measure ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’ critically because the infant cinema has had no time to build a Shakespearean tradition. Whatever its flaws, it is a work of high ambitions and unflagging interest, and it provides a stimulating evening in the cinema. It is a credit to Warner Brothers and to the motion picture industry.”

Peter Ibbetson (1935, dir. Henry Hathaway) – reviewed November 8, 1935

“The striking thing about the new screen version of ‘Peter Ibbetson’ at the Radio City Music Hall lies in the identity of its director, Henry Hathaway. Known almost exclusively for his ‘Lives of a Bengal Lancer,’ Mr. Hathaway bridges the spiritual gulfs between that rousing super-Western and the fragile dream world of duMaurier’s sentimental classic with astonishing success. With his directness and his hearty masculine qualities, he skillfully escapes all the lush pitfalls of the plot and gives it a tenderness that is always gallant instead of merely soft. The photoplay, though it scarcely is a dramatic thunderbolt, possesses a luminous beauty and a sensitive charm that make it attractive and moving. Under Mr. Hathaway’s management Miss Ann Harding, who has been losing prestige lately, gives her finest performance, while Gary Cooper fits into the picture with unexpected success.

“Hathaway’s special triumph is in the dream sequences, which could have degenerated so easily into the double-exposure ghostliness of the recent ‘Return of Peter Grimm.’ Carefully avoiding the temptation to bathe the screen in misty photography and heavily remind his audiences that this is a spirit world, he abandons conventional screen devices and boldly insists on the reality of the dreams. This is a shrewd modern touch and it goes for to make duMaurier’s celebrated love story dramatically effective. The astral sphere on which the lovers moved through a lifetime of happiness, while their bodies remained shackled to the earth, thus becomes to us what it was to them, more vividly actual than the daytime world that kept them apart.”

Your Uncle Dudley (1935, dirs. Eugene Forde and James Tinling) – reviewed December 12, 1935

“The Center Theatre offers a meager and unassuming little comedy of small-town life as its pre-Christmas contribution to the film sector. We cinema reviewers, when films as unobtrusively dull as ‘Your Uncle Dudley’ happen along, make a minor virtue of anemia by applying such kindly adjectives as amiable to them. Although ‘Your Uncle Dudley’ is unpretentious, it is also aggressively commonplace. It seems to have been manufactured for the tail end of double bills and it barely possesses the laughs for a competent two-reeler. Consequently it scarcely impresses this column as an amiable motion picture. In the title rôle Edward Everett Horton fidgets familiarly as a rural Caspar Milquetoast who finally rebels against the tyranny of his sister. The chances are that, like Cole Porter’s first sniff of cocaine, it will bore you terrifically, too.”

The Ghost Goes West (1935, dir. René Clair) – reviewed January 11, 1936 (the day before Andre Sennwald’s death)

“This review seems to require a preamble. Faced with an event of such imposing interest as René Clair’s first English-speaking film, it is a grave temptation to go in for comparisons. That is distinctly the wrong approach to ‘The Ghost Goes West,’ which M. Clair made in England for Alexander Korda. The film is not pure Clair, or even characteristic Clair, because for the first time he is working in a strange language and from a script that is not his own. Robert Sherwood, who wrote the screen play, is as much a part of the film as the director himself. Consequently, the new film at the Rivoli Theatre reveals little stylistic relation to the precious handful of French films which bear his name. Nor does it possess, except in isolated scenes and details, any such distinct form as might identify it immediately with the cinema’s finest master of comedy.

“This is an unhappily pompous way to introduce such a gay, urbane and brilliantly funny film as ‘The Ghost Goes West.’ The Messrs. Sherwood and Clair are toying a gracefully long, loud laugh at the expense of American millionaire art lovers and European tradition. Their ghost, very solidly played by Robert Donat, is of the Scotch persuasion, he is a handsome devil, and even after 200 years he has an eye for the ladies. His adventures with the castle that is dismantled and transported to America are always merry and sometimes sharply satirical.

“…Mr. Donat, who revealed his brilliant talent for romantic comedy in ‘The Thirty-nine Steps,’ plays his two rôles with fine zest and even manages a Scottish burr with fair success. Eugene Pallette is uproariously solemn as the millionaire and Jean Parker plays the daughter engagingly. It would be criminal not to single out Morten [sic] Selten for special mention. As the proud old head of the Glourie clan he makes such an indelible impression during his brief appearance on this earth that his ghostly dialogues with his son acquire an added hilarity. ‘The Ghost Goes West’ is the first important film of the new year, and a joyous one. It is the cream of an ebullient jest.”