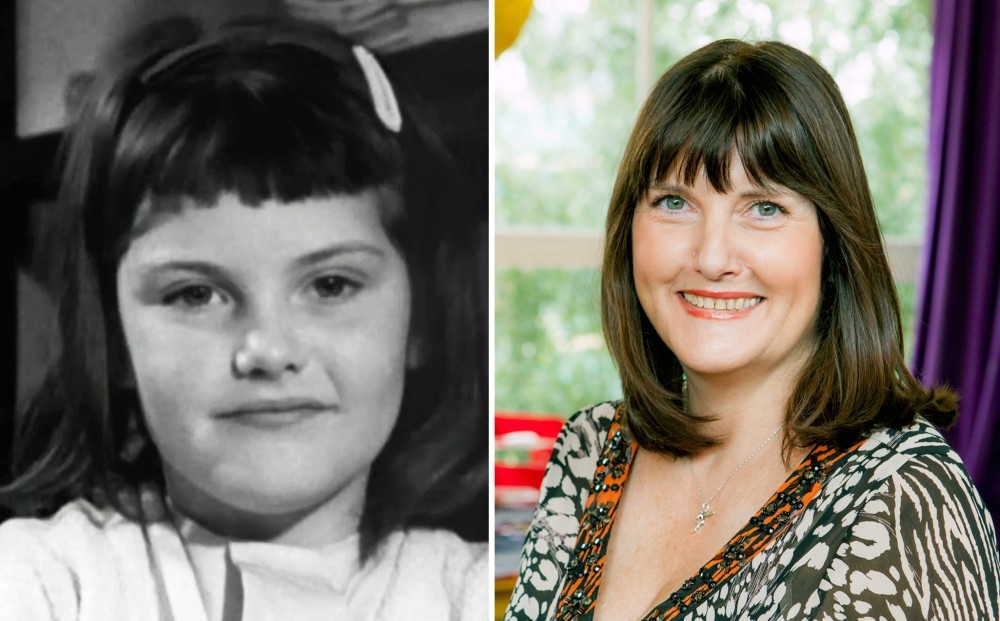

Cinematographer Natasha Braier and producer/director Alma Har’el on the set of Honey Boy, 2018. (Photo: IndieWire via Amazon Studios)

Here are thirty-six new movies due to be released in theaters or via other viewing platforms this November, all of which have been directed and/or photographed by women. These titles are sure to intrigue cinephiles and also provoke meaningful discussions on the film world, as well as the world in general.

NOVEMBER 1: The Etruscan Smile (dirs. Oded Binnun and Mihal Brezis) – San Joaquin International Film Festival synopsis: “Rory MacNeil, a rugged old Scotsman, reluctantly leaves his beloved isolated Hebridean island and travels to San Francisco to seek medical treatment. Moving in with his estranged son, Rory’s life will be transformed, just when he expects it least, through a newly found love for his baby grandson. The Etruscan Smile – the feature debut of Israeli filmmakers Oded Binnun and Mihal Brezis – is based on the bestselling book La sonrisa etrusca by Spanish author Jose Louis Sampedro, with the story being transposed to Scotland and the United States. The heart of the film is another unforgettable role by actor Brian Cox.”

NOVEMBER 1: Harriet (dir. Kasi Lemmons) – Time review by Stephanie Zacharek: “Sometimes it’s hard to conceive of awe-inspiring historical figures like abolitionist hero Harriet Tubman as living, breathing people. But a single visual cue can make a difference: a recently discovered photograph shows a younger Tubman, a contemplative, vibrant-looking woman in a stylish dress. That’s the Tubman director Kasi Lemmons brings to life in her carefully observed biographical film Harriet: it’s as if Tubman walks among us, melting away the years between her life and ours.

“Cynthia Erivo plays Tubman, whom we first meet as a slave–her birth name is Araminta Ross–on a farm in Bucktown, Md., circa 1849. She’s married to a free black man and yearns for freedom herself, at least partly to escape the sinister advances of her master’s son (an oily Joe Alwyn). Araminta pulls off a daring escape, even leaping from a bridge when she finds herself cornered by the dogs and men on horseback who are quite literally hunting her. She makes her way, at great risk, to Philadelphia, building a new life for herself with the help of a sophisticated businesswoman and adviser (played, with glittering vitality, by Janelle Monáe). But the woman who now calls herself Harriet Tubman can’t forget those she left behind. She returns again and again to Maryland’s Eastern Shore, often in disguise, to guide other slaves to freedom. The dangers increase with each trip.

“Lemmons–who has directed some splendid pictures over the years, among them Eve’s Bayou and The Caveman’s Valentine–is fully alive to both the danger and beauty of the landscape of the American South–even the shape of a tree, craggy and twisted or lush with leaves, could be either a warning or a welcome. Erivo shines through it all, giving us a glimpse into the mind of a steadfast woman of purpose. Her Tubman is as bold and alive as the woman staring at us from that photograph. The directness of her gaze is the ultimate challenge.”

NOVEMBER 1 (NY), NOVEMBER 8 (LA): Light from Light (dir. Paul Harrill) (DP: Greta Zozula) – RogerEbert.com review by Monica Castillo: “There’s no right way to grieve the death of a loved one. Some of us chose to keep the sadness to ourselves, others talk through it or express it in creative ways. We move on, or we don’t. We take comfort in the small signs that they might somehow still be with us or we lay their memory to rest in the back of our minds.

“In Paul Harrill’s gentle drama Light from Light, a paranormal investigator and single mother named Sheila (Marin Ireland) is introduced to a widower, Richard (Jim Gaffigan), struggling with the recent death of his wife in a plane crash. He believes he can feel her presence but isn’t sure, and his questions have stumped his priest, Father Martin (David Cale), who in turn, invites Sheila to help. Together, they will try to find out if there is indeed a spirit in Richard’s home and hopefully, give him some sense of closure, whatever that may look like. Alongside the grown-ups’ heartaches are the troubles of young love between Sheila’s son Owen (Josh Wiggins) and his earnest girlfriend, Lucy (Atheena Frizzell).

“This young love acts as a kind of narrative counterweight to the heaviness of what the adults are grappling with – a love that was cut short by death yet lingers on. They are each learning their way into this new emotional space through Harrill’s quiet direction. In many scenes, emotions sit in silence, written on the faces of the actors but left unspoken, like when Sheila is unsure of what to say to the grieving widower who’s turned to her for answers or when her son challenges her parenting. Originally, Owen is the one afraid to get hurt if he falls for Lucy. Then as he lets his guard down, his mom tries to intervene in an attempt to save her son from whatever possible heartbreak awaits. But some feelings just need to be felt, be they good, bad or confusing.

“Harrill, who wrote and directed the film, isn’t as interested in the supernatural elements in the film as he is with the story’s few players. There’s a lot of room for emotions to breathe and wash over its characters, but never does it tip over into excess. It’s a muted portrait, quietly restrained in some ways that may feel restrictive but in others, remarkable in how far the actors can take these emotions without overacting. Ireland and Gaffigan give incredibly nuanced performances portraying characters who have more hurt behind their eyes than they let on. For Richard, it may be easy to see why he’s upset, but no amount of words could explain what he’s going through. In Sheila’s case, there are hints of a kind of an adrift, directionless frustration after the end of a relationship also meant she had to leave their shared paranormal group. In helping Richard find closure, Sheila might also close a chapter in her own life and move on.

“Light from Light sticks to a subdued aesthetic throughout the characters’ emotional journey. When Sheila and Richard trek up the Smokey Mountains to the crash site where his wife died, cinematographer Greta Zozula finds her darkest shades of grey and forest green, swallowing the characters in a somber state of sadness. Yet, in a sunny moment not long after, there’s a warm glow of hope and healing unmistakable on both the actors’ faces and the scene itself. The melodic acoustic score from Adam Granduciel and Jon Natchez complements the movie’s gentle approach to grief and love like a comfortable sweater on a rainy autumn day, striking the right chords at just the right times.

“Although it takes its time getting to where it’s going, Light from Light does eventually reach its destination. For a movie about grief, it’s surprisingly even-handed, not too melancholic, heavy or existential but mostly pensive. Those quiet scenes between actors allow the audience to fill in the unclaimed screentime with their own self-reflection. They’re also reminders of how unused we are to these silences and awkward it feels when we don’t have the right words to comfort someone. Then again, most of us never do enough listening to one another, awkward silences included, which makes Light from Light a tender lesson in listening to and observing one another.”

NOVEMBER 1 (LA), NOVEMBER 15 (NY): The Portal (dir. Jacqui Fifer) – City Cinemas Village East Cinema synopsis: “The Portal is an experiential documentary created as part of a bold, global vision to shift humanity out of a state of crisis. It brings to life the stories of six people who overcame adversity using stillness and mindfulness, inspiring the audience to follow in their footsteps and realize the unique potential that all humans have to change our world. With insights from three of the world’s foremost futurists–and a robot–the film unfolds into a beautiful, audiovisual spectacle that takes the viewer on their own mindfulness journey through the pain, joy and memory fragments of life.”

NOVEMBER 1: Queen of Hearts (dir. May el-Toukhy) – Variety’s Sundance Film Festival review by Guy Lodge: “‘Sometimes what happens and what must never happen are the same thing,’ says Anne, a successful lawyer given to flouting expected codes of conduct, midway through Queen of Hearts. As excuses for an offense go, it’s on the slender side — a slightly more formal version of ‘the heart wants what it wants’ — but Danish director May el-Toukhy’s sleek, engrossing melodrama isn’t liable to interrogate its characters. ‘What must never happen’ makes for a better story, after all, and her film leads its characters into that territory with a detachment as cool as its polished Scandi interiors. The heat comes from viewers’ own emotional response to its doozy of a central transgression, as middle-aged, comfortably married Anne (Trine Dyrholm) initiates a reckless sexual affair with her troubled teenage stepson Gustav (Gustav Lindh): The premise’s ‘what?!’ factor is so luridly high that the ‘why?!’ one gets pushed to the background.

“That this approach holds water for as long as it does comes largely down to the sharp, subtle gifts of Dyrholm, one of those actors who truly has to strain for a false note. Her finely shifting body language and simultaneously knowing, querying gaze go a long way toward making in-the-moment sense of an intelligent character’s most brazenly stupid decisions, even as we begin to suspect that the script, by el-Toukhy and Maren Louise Käehn, may be as bemused by her as we are.

“In a conversation piece pitched halfway between the delicate Sirkian tragedy and Adrian Lyne at his most sensational, it’s the overridingly controlled nature of proceedings — from performance to production design — that keeps Queen of Hearts from sliding into the hysterical silliness that its provocations invite. You can’t quite turn away from it even as you don’t quite believe it: That will carry el-Toukhy’s sophomore feature (formally, a sizable step up from her 2015 romantic comedy Long Story Short, also featuring Dyrholm) far on the international arthouse circuit, and ought to net the interest of international producers in the director’s next move. (Meanwhile, you can practically envisage a Robin Wright-starring U.S. remake of Queen of Hearts while watching it.)

“At a leisurely 127 minutes, the film takes time to build its crisis, while dropping hints from the off that something is rotten in, if not the state of Denmark, at least the state-of-the-art Danish home that Anne shares with her Swedish husband Peter (Magnus Krepper), an equally high-flying doctor, and their adorable twin girls. Though they’re an ostensibly enviable family, Peter confesses to wishing Anne were a little more submissive, while both partners are wedded to their jobs first and foremost. Their overall happiness seems brittle, cushioned by privilege but vulnerable to the slightest tremor: They get more than that when Gustav, Peter’s estranged son from his first marriage, moves in, having been expelled from both his school and his mother’s home in Sweden.

“With father-son relations all but frozen over, Anne at first quietly inserts herself into the void as Gustav’s ally, covering for his misdeeds and buying him a high-end laptop; as a lawyer who specializes in representing young victims of abuse, her overtures of generosity to the sullen, withdrawn boy at first seem an extension of her job. Yet that particular character detail only confuses the picture once her kindness crosses the line into intimacy, first via conversation, then a kiss, then a full-blown sex scene shot with a very Scandinavian fusion of explicit candor and white-linen restraint. As one who deals compassionately with trauma-afflicted children on a daily basis, does she not view herself as a perpetrator of sexual assault? Has she legally talked herself into a trickier view of the situation? Or is she not thinking at all — a woman of the law finally giving in to unfiltered urge?

“All these possibilities are kept afloat by Dyrholm’s fierce, fascinating performance — with an equally prickly, nuanced assist from Lindh, who can vulnerably switch gear in a single scene from precocious flirt to stunted brat. But if Queen of Hearts earns credit for casting no judgment on either character, its refusal to let us into anyone’s head begins to feel less like philosophical distance than a bit of a psychological dodge, particularly as the situation collapses into calamity, and Anne’s actions progress from heedlessly self-serving to clinically so. In one exchange between the lovers, el-Toukhy and Käehn tease the possibility that Anne may have a history of victimhood herself, before retreating into pointed ellipsis.

“There’s a lot to unpack there, but doing so might muddy up the film’s gorgeous, compelling ice-noir surface — so pristinely maintained by Jasper J. Spanning’s fluid, limpid camerawork and the tight string motifs of Jon Ekstrand’s anxious score. An uglier, more abrasive film could be made from this unpleasant story, though in the #MeToo era, the more elegant, aloofly accomplished one el-Toukhy has made should still prompt a flurry of debate over its portrait of a female predator. ‘You don’t understand how people work,’ says one exasperated character to another late in proceedings; if Queen of Hearts has a driving thesis beneath its glassy, alluring intrigue, it’s that no one really does.”

NOVEMBER 8: Ballet Blanc (dir. Anne-Sophie Dutoit) – Downtown Los Angeles Film Festival synopsis: “Set in a remote town in the Western U.S., a young boy who has a passion for ballet, appears out of nowhere. After being discovered in a church choir, he’s eventually adopted by a peculiar and frightening lonely local woman who has dark ambitions for him. She seems to be his master, but is she, really? The county eventually sends a social worker to investigate a particularly gruesome incident involving the boy. But this endearing youngster has a mind of his own, exerting his power and will over everyone. His frightening grand plan eventually comes into play, as he’s not who he appears to be, or is it our perception of him? Behind his innocent smile lies a gruesome secret that may change the world.”

NOVEMBER 8 (NY): A Fish in the Bathtub (dir. Joan Micklin Silver) – Quad Cinema synopsis: “Legendary comedy duo (and real-life husband and wife) Jerry Stiller and Anne Meara star as the constantly bickering couple at the center of this sprightly comedy from writer-director Joan Micklin Silver (Hester Street, Crossing Delancey). When Sam (Stiller) stubbornly refuses to get rid of the new pet carp he’s unleashed in their bathtub, Molly (Meara) finally decides she’s had enough and moves in with their married son Joel (a young Mark Ruffalo). Desperate to get his mother out of his hair (and house), Joel enlists his boy-crazed travel agent sister (Jane Adams) to help repair their parent’s relationship—meanwhile he’s tempted toward infidelity by a flirtatious client (Missy Yager). Replete with Micklin Silver’s signature wit and loving lensing of New York’s city streets and suburbs, this little-seen gem is fun for the whole neurotic family.”

NOVEMBER 8 (in theaters & on DirecTV): Good Girls Get High (dir. Laura Terruso) – Variety’s Los Angeles Film Festival review by Courtney Howard: “For the most part, successful teen comedies follow a tried and true formula. Memorable high school movies typically feature characters who feel like outsiders floundering hilariously en route to the revelation that simply by being themselves, they’ll find what’s eluded them for so long. John Hughes knew it well, as did his imitators, realizing that even small deviations can be enough to refresh the genre for a new generation. Full of charm, humor, and heart, director Laura Terruso’s Good Girls Get High mixes it up, delivering a ‘high’ concept comedy in which the two kids least likely to go astray do exactly that.

“High school senior Sam Jensen (Abby Quinn) and her best friend Danielle Compton (Stefanie Scott) have always lived by the rules. While the rest of their classmates were out doing the crazy, stupid things normal teens do, the two overachieving co-valedictorians were either crushing their extracurriculars, rollerblading around town, or enjoying wholesome activities on Friday nights. However, when the pair discovers they’ve been voted the school’s ‘Biggest Good Girls,’ it sends Danielle into a tailspin. She convinces Sam there’s a ticking clock on their irrational, wild days and if they don’t do something about it now, they’ll be locked into these roles for the rest of their lives. After Sam discovers a joint hidden in her single father’s (Matt Besser) laundry, the two pals start behaving badly with their very on-brand style of pragmatism.

“Working from the blueprint of Sarah Miller’s book, Terruso and co-writer Jennifer Nashorn Blankenship demonstrate a clear understanding of what it takes to craft a finely-tuned, female-forward feature. The gals’ friendship is always at the forefront of the action. Our heroines are smart, funny, capable young women, who, despite their wits being impaired, remain true to themselves. Occasionally the perspective slips into their psyches, showing their world through fuzzy ‘weed cam’ shots, Sam’s daydreamy longings for science teacher Mr. D (Danny Pudi), or Danielle’s slo-mo fantasies about harlequin-romance-haired hunk Jeremy (Booboo Stewart).

“Sam and Danielle’s schoolgirl crushes aren’t their endgame; their reward is the fidelity of their friendship, and the male characters serve to complement that. It even subverts traditional roles: The character who’d usually be written as a ‘mean girl,’ social activist influencer Ashanti (Chanté Adams), is admired and supported by the gals. The character who’d stereotypically be portrayed as the condescending authority figure, pregnant cop Patty (Lauren Lapkus), finds a lovely kinship with the pair.

“The filmmakers also know how to build a highly comedic scenario. The tomfoolery the two find themselves embroiled in is absurdly funny. Though there are raunch-com elements here, the gross-out factor is fairly tame. For instance, instead of getting scatological during an intimate encounter where one character fears her upset stomach will ruin the mood (an operatic aria perfectly captures her anxiety), it’s merely gaseous emanations. An accidental sexting is handled practically. By framing the girls’ shenanigans with Sam’s Harvard admissions confessional, Good Girls delivers the exposition with witty commentary.

“Augmenting the narrative drive, cinematographer Benjamin Rutkowski bathes the protagonists’ world in saturated colors. Sam’s sanctuaries, such as her bedroom and family ice-cream shop, are color-coded in welcoming teals and yellows. Danielle surrounds herself with light pastels. Composer Jay Israelson provides a warm ’80s-inspired synth score that would’ve suited Hughes himself.

“With heartening, encouraging messages that speak to the target audience and beyond, Good Girls Get High doesn’t stray too far from the formula, but manipulates it in such a way that feels fresh.”

NOVEMBER 8: Honey Boy (dir. Alma Har’el) (DP: Natasha Braier) – Film Comment review by Michael Sragow: “Shia LaBeouf, who peaked commercially in three Transformer films and hit a creative pinnacle as John McEnroe in Borg and McEnroe (2018), has written a raw, brilliant script for Honey Boy. This fictionalized cinematic memoir is unabashed ‘drama therapy’: it grew out of LaBeouf’s writings in rehab after ranting at police while on location for another film in Savannah, Georgia.

“Whether or not it works as therapy, Honey Boy is a wonderful movie, directed confidently and intuitively by documentary-maker Alma Har’el in her first fictional feature. With emotion-charged transitions and elisions, Har’el glides between overgrown, self-destructive Otis Lort (Lucas Hedges), locked into denying his domestic PTSD, and precocious, high-achieving Otis (Noah Jupe), the child actor on the rise who pays his father James (played by LaBeouf himself), a recovering alcoholic/addict, to be his chaperone. Har’el has beautifully braided present-tense action and flashbacks (and fantasies) into this portrait of the artist as an abused son.

“When 22-year-old movie star Otis thanks his rehab supervisor Alec (Martin Starr) for telling him to unleash a primal scream, Alec, no dummy, asks Otis if he’s ‘sincere’ or if he’s ‘acting.’ Otis levels with him: ‘Both.’ What other answer could such a super-intense performer give? Otis is the kind of actor who psychs himself up on the set of a giant, Transformers-like action movie but can’t come down from the high. He carries his thespian prowess like an invisible shield: When a policeman cuffs him off-set, Otis absurdly tells the cop that he’ll be sorry when he learns how good Otis is at what he does.

“Otis’s father occupies the red-hot center of the psychodrama. LaBeouf frees himself of vanity as 45-year-old James, a Vietnam veteran who trained in Commedia dell’arte and entertained crowds as a rodeo clown. James now reads lines with his boy in his own insistent voice and modified New Orleans drawl and coaches him in slapstick farce. Otis appreciates James’s ‘instincts,’ though the boy has been developing a better sense of what works for him comedically. The two have cobbled together a sort-of life between TV-sitcom studios and a seedy motel, where the courtyard is no garden and the neighbors across the way are hookers. While James has been clean for four years, he still can’t tamp down his temper at a 12-step meeting.

“We may fear what he’ll do if he stumbles, since what he does when he’s sober is shocking enough. He’s so unsure of how to act like a father that he won’t hold his son’s hand: he’s afraid people will mistake him for a ‘chicken hawk.’ He’s a registered sex offender because of an outrage he committed during an alcoholic black-out long ago. James is also ruinously jealous. It affronts him that his ex-wife enrolled Otis in the Big Brother program to acquaint him with a positive male role model. James can’t abide the weathered, benign presence of Tom (Clifton Collins Jr.), Otis’s Big Brother. But in one of the film’s many sly, expressive asides, we learn that Tom, a passport specialist for the State Department, would be happy to help the Lorts with their passports even after James curses him out and tosses him into the motel swimming pool.

“At the movie’s volcanic core, James frustrates both 12-year-old Otis’s attempts to communicate with him son-to-father, and 22-year-old Otis’s struggle to reckon with his father’s legacy. (Otis has become an angry addict himself.) LaBeouf describes this film as an exorcism, but he molds and plays James with superb control, in ways that serve the story precisely. LaBeouf makes us believe that this troublesome dad has indeed turned his son into an artist, not merely because of the pain he caused, but also because of his passionate commitment to the boy’s creativity (and also, perhaps, his unconventionality). James tells Otis that his mom has gotten herself a job in case Otis fails as an actor: He insists that he’s Otis’s ‘cheerleader’ as well as his physical trainer. When James teaches Otis how to juggle using balled-up pairs of socks, he makes him do ten pushups if he drops one.

“For viewers to buy this film’s premise, there must be heft to James’s engaging silliness as well as his engulfing fury. And LaBeouf provides it, without going over the top. LaBeouf’s James tucks in his sizable paunch as he mounts his motorcycle and, on the road, covers his mouth with a raggedy bandanna. Wearing oversized circular glasses and a do-rag, he recalls rodeo routines he choreographed with an athletic chicken. As LaBeouf plays him, James is sometimes a human sight gag, sometimes a one-man counterculture. Despite his cruelty, we feel James’s agony when he confesses that it’s humiliating to draw a salary from his son. Otis is sadder and wiser and can be cruel himself: ‘You wouldn’t be here if I didn’t pay you,’ the boy says.

“As movie-star Otis reluctantly grapples with his memories of childhood, Hedges masters shadow boxing: he must spar with LaBeouf’s James, who interacts with him only in flashbacks, nightmares, or reveries. Hedges is a wizard at conveying compacted, often boobytrapped emotions. It helps that Har’el surrounds him with such a smart ensemble. Martin Starr as his group leader Alec and Laura San Giacomo as his psychologist Dr. Moreno defuse his hardboiled skepticism toward therapy with unexpected patience, curiosity, and incisiveness. Byron Bowers provides a relaxed comic counterpoint as Percy, Otis’s roommate, who drifts into treatment as blissfully as he does into sleep. Alec jokes that Percy may be too good—by which he means, too happy—at hugging himself to release hormones. Bowers’s ultra-satisfied face provides the visual punch-line.

“Even in this heady company, young Jupe gives the performance of the movie. He puts his character on a psychic tightrope and never misses a step. He gives Otis at age 12 the elan of a born star and a soulful artist’s face: sometimes his expressions betray baseline feelings; at other times they stress the drama playing out around him. He understands the conflicts between his father and mother (Natasha Lyonne, whom we do not see, just hear over the phone). He knows their fights will go on forever. In the most extraordinary scene, James refuses to get on the phone with his former spouse. Otis hangs on to the handset and relays each parent’s horrific condemnations to the other. Jupe delivers them like a pro.

“Har’el and cinematographer Natasha Braier imbue the film with an empathetic lyricism. The exchanges between Otis and a young hooker referred to in the credits as ‘Shy Girl’ (FKA twigs) redeem the whole notion of contemporary mime. The boy actor and Shy Girl seal their affection in a silent bit that combines elements of sorcery and softball. When they snuggle up in bed, they recover each other’s innocence, even after Otis does what he thinks he should do: he grabs some cash and pays her.

“Har’el and Braier bring a gnarly shimmer to poolside dreams and roadside pipe-dreams. Along with LaBeouf, they bequeath the roughest characters with the tenderest mercies.”

NOVEMBER 8 (NY/LA): The Kingmaker (dir. Lauren Greenfield) (DPs: Shana Hagan and Lars Skree) – The New York Times review by Manohla Dargis: “It was always a little too easy to laugh at Imelda Marcos. The gold and the kitsch, the fine art and the tchotchkes, the rows of bedazzled shoes and the towering dome of shellacked hair — it was all so very much, so very vulgar, so very, very expensive. During the roughly two decades that Marcos was the first lady of the Philippines, she became famous for lavish habits that make the Kardashians seem like skinflints. Even after the Marcos family fled the Philippines in 1986, her extravagance often received more attention than her role in what was called a ‘conjugal dictatorship.’

“In the documentary The Kingmaker, Lauren Greenfield trots out the plunder and of course the shoes — those notorious emblems of Marcos’s excess — but also examines the appalling costs of that luxury. It’s an ugly story shrewdly told, with a sense of humor and also a deeper feeling for history. In the years since Marcos and her husband, Ferdinand (who died in exile, in Hawaii, in 1989), were ousted after the People Power Revolution, too many journalists have called on her to gawk and dish. Greenfield, a fine-art photographer turned filmmaker, has something else in mind, as telegraphed by the aerial shot of ramshackle Manila shanties that starts the movie.

“This opener introduces Greenfield’s dialectic approach, which emerges slowly. Under her scrupulous gaze — the directors of photography are Lars Skree and Shana Hagan — Marcos, a.k.a. the Iron Butterfly, floats through her homes, tended to by anxious aides. She chats under a Picasso, poses before a Michelangelo. She displays reams of legal documents from her many court battles and drifts down memory lane, at one point showing off photos of herself with the woman she calls Mrs. Mao (Jiang Qing) and with Richard M. Nixon. When Marcos accidentally knocks over some photos, shattering the glass in the frames, the moment vibrates with metaphoric force.

“Greenfield doesn’t explain how she secured her remarkable access, though she clearly has a gift for wrangling the self-obsessed. Her documentary The Queen of Versailles (2012) centers on a billionaire couple (primarily its title subject, Jackie Siegel) who planned to build the largest privately owned house in the United States. Perhaps Marcos saw Queen of Versailles and liked what she saw. Or maybe she simply wanted the attention to stoke her political ambitions, specifically from a respected chronicler like Greenfield. It’s hard not to wonder if Marcos regarded the filmmaker as another would-be courtier or even an acquisition (a mistake).

“Whatever the case, as Greenfield quickly reminds you, one way into a narcissist’s heart is to turn on a camera and microphone, and let vanity take over. From the instant that Marcos appears in The Kingmaker — gliding through the streets of Manila in a van as if in a mobile throne — it’s obvious that she remains ravenous for attention, whether from the camera or from the indigent people clamoring outside her window. It’s unsurprising that she rarely appears alone here, though it’s unclear if she needs all her helpers or is simply accustomed to armies of servants. This is, after all, a woman who apparently had a maid whose sole job was to care for her jewelry.

“Despite the early images of conspicuous poverty, Greenfield initially seems to be going somewhat easy on her subject. ‘During my time, there were no beggars,’ Marcos says soon after the movie begins, while cruising past destitute people and rundown streets. Greenfield doesn’t overtly challenge this assertion, perhaps because it’s so ridiculous. Instead, she cinematically builds a case against Marcos by folding in increasingly tough interviews with brutalized anti-Marcos activists and by deploying a surgical attention to detail: images of grasping hands are contrasted with manicured hands holding money; stuffed animals are set against images of real abused wild ones.

“Marcos, who turned 85 in 2014, the year that Greenfield started shooting, continues to look remarkably robust as the years pass by, never more so than in front of the crowds that swell in size and intensity at the political rallies she attends. As the throngs burgeon, the movie’s tone grows ominous. Marcos’s children enter and exit, flexing their own political power. Her son, Bongbong, runs for vice president. An alliance emerges between her daughter Imee (also a politician) and the current president, Rodrigo Duterte, whose violent, so-called war on drugs has resulted in the deaths of an estimated 20,000 people and international condemnation.

“As Greenfield opens The Kingmaker up, the Philippines’ past and present move uneasily into alignment, and the movie becomes more interesting and far more disturbing. Notably, it also becomes less about one woman, her malevolent charms and quirks, and develops into an unsettling look at imperial power. That said, there are moments when you wish that Greenfield had pushed harder in The Kingmaker, say, by taking a closer look at American intervention in the Philippines. But when she interviews an old friend of the Marcoses who chortles about American support for despots, the movie — like his comment — becomes the tragedy it was meant to be.”

NOVEMBER 8 (LA), NOVEMBER 22 (NY): Mr. Toilet: The World’s #2 Man (dir. Lily Zepeda) (many DPs, including Siyan Liu) – Hot Docs Canadian International Documentary Festival synopsis by Gabor Pertic: “The global sanitation crisis finds an unlikely and eccentric hero in 60-year-old Singaporean Jack Sim, also known as Mr. Toilet. By blending a lighthearted sense of humor with some compelling and unnerving statistics, he cuts through the cultural taboos of a topic that tends to make people uncomfortable. That discomfort, however, comes at a deadly cost. Nearly a third of the world’s population is put at risk by lack of access to proper sanitation, be it unsafe outdoor conditions or improper sewage systems. While Jack’s efforts are on a global scale, a major part of his advocacy is focused on India, where 200,000 children die each year from poor sanitation and women are assaulted in public spaces for lack of private bathrooms. Mr. Toilet faces large corporate fights and thinning resources, but his sense of fun and fervor reveal a determined hero that the world needs more than ever.”

NOVEMBER 8: My Home India (dir. Anjali Bhushan) – London Indian Film Festival synopsis: “This inspirational documentary will have you in tears and every Indian glowing with pride. The film essentially uncovers a little-known story of unimaginable humanity, generosity and kindness. Towards the end of WW2 the Polish ambassadorial team in Bombay, led by the determined heroine, Kira Banasińska and supported by local Indian communities including the principalities of Kolhapur, Jamnagar and several others, dispatched a convoy of food relief and other essentials, thousands of miles to Iran, where Polish refugees from Soviet Siberian labor camps had found their way on foot and were suffering, mal-nourished. An expedition was planned with a novel idea, to bring 5,500 women and children back into India in the supplies trucks. This expedition was not so simple. It took Kira’s resilience and indefatigable energy as a Red Cross leader, to create refuge for them and welcome them to a dedicated settlement in India in three critical places, Vallivade, Panchgani and Jamnagar. Over 70 years later a number of now elderly Polish people return to a town, Vallivade, on the outskirts of Kolhapur, Maharashtra and Panchgani, where they were able to find safety and discover the joys of childhood.”

NOVEMBER 8 (streaming on Netflix): Paradise Beach (dir. Xavier Durringer) (DP: Marie Spencer) – WTFilms synopsis: “From Cannes selected director Xavier Durringer comes an intense look at the gangster life in paradisiac Thailand.

“After a heist in Paris, five friends live the good life in Phuket: beautiful girls, swimsuits and Havaianas on their feet every day. They own and run go go bars, beach restaurants, hotels and clubs. They were nothing in France, now they’re kings in Thailand.

Until Mehdi (Sami Bouajila), who was left behind at their last job and considered the meanest of them all, is released from prison after 15 years of silence protecting them.

Now he arrives in Phuket to meet his brother and friends. But mostly to get his long-awaited share. The problem is, there’s no share left. That’s when Mehdi decides to turn their paradise into hell.

“Shot on locations where no cameras were ever allowed before, and boasting some of the biggest French rap stars on the soundtrack and on the screen, Paradise Beach will take you for a ride with a new generation of criminals.”

NOVEMBER 8: Watson (dir. Lesley Chilcott) – Tribeca Film Festival synopsis by Dan Hunt: “Captain Paul Watson has dedicated his life to fighting for one thing; to end the slaughter of the ocean’s wildlife and the destruction of its ecosystems. Co-founder of Greenpeace, Watson is part pirate, part philosopher in this provocative film about a man who will stop at nothing to protect what lies beneath. Director Lesley Chilcott and producer Louise Runge bring us incredible archival footage from decades of Watson’s activism braided with personal stories and beautiful underwater sea life footage to tell the story of a true champion for the environment. Informative, moving, and disturbing, Watson is a must see for anyone who is concerned about the future of our oceans and the planet.”

NOVEMBER 13 (NY), NOVEMBER 22 (LA), NOVEMBER 29 (other cities): Mickey and the Bear (dir. Annabelle Attanasio) – Seattle International Film Festival synopsis by Marcus Gorman: “”‘Truth is, one day you’re gonna forget about me; that’s just the way it is.’ Mickey Peck (Camila Morrone, Never Goin’ Back) swears to her father Hank (James Badge Dale, The Standoff at Sparrow Creek) that’ll never happen, but as she approaches her high-school graduation, she realizes he might have a point. Since her mother’s untimely death, Mickey has dedicated her life to taking care of Hank, whose leg injury while serving in Iraq has turned him into an alcoholic and full-blown Oxycontin addict. Even if he does get better, of which there is no guarantee, what’s left for her in the small town of Anaconda, Montana? Maybe the new kid in school (Calvin Demba, Kingsman: The Golden Circle) and the no-nonsense town psychiatrist (Rebecca Henderson, ‘Russian Doll’) can inspire her to follow her dreams of leaving Montana behind forever for the sunny shores of the West Coast. In her feature debut, writer/director Annabelle Attanasio (also an actress best known for her work on Steven Soderbergh’s ‘The Knick’ and CBS’s ‘Bull’) demonstrates extraordinary restraint with a story that could have very easily fallen into garish melodrama, never shifting focus away from Morrone and Dale’s outstanding performances. ‘It wasn’t supposed to be like this, darling,’ Hank drunkenly tells his daughter one night. And it’s not too late to change that.”

NOVEMBER 15 (in theaters), NOVEMBER 29 (streaming on Netflix): Atlantics (dir. Mati Diop) (DP: Claire Mathon) – IndieWire’s Cannes Film Festival review by Eric Kohn: “Several recent movies have explored the refugee crisis as a deadly proposition, from the documentary Fire at Sea to Mediterranean, both of which focus on dramatic attempts to cross the ocean on rickety boats. The striking distinction of Mati Diop’s Atlantics is the way it magnifies the experiences of those left behind. Diop’s gorgeous, mesmerizing feature directorial debut focuses on the experiences of a young woman named Ada (Mama Sané) stuck in repressive circumstances on the coast of Dakar after her boyfriend vanishes en route to Spain. But it’s less fixated on his departure with other locals than its impact on Ada, and the community around her, as it contends with the eerie specter of the boys who went away.

“An actress and filmmaker whose experimental shorts touch on similar themes, Diop’s first feature doesn’t always fit together from a narrative perspective, but it musters such an absorbing vision of an alienated seaside life that not everything needs to add up for the atmosphere to take hold. Atlantics takes the form of a dazzling Senegelese ghost story in which everyone’s haunted by the desire to escape.

“But the movie begins as a more grounded romance, with Ada and Souleiman (Ibrahima Traoré) roaming around the beach in carefree fashion, even as the young fisherman seems troubled by something he can’t quite express. By the next day, Ada figures it out: Souleiman and some of his peers have escaped to sea, following a route to Spain in a rickety pirogue like so many before them, few of them make it across. That leaves Ada forced to contend with an arranged marriage to Omar (Barbara Sylla), a wealthy immigrant who seems to regard her as little more than a prop. But when the wedding is sabotaged after someone sets Omar’s mattress on fire, Ada begins to suspect that Souleiman has returned in secret.

“So…where is he? Struggling with the emptiness in her life and the traditionalist expectations of her Muslim family, Ada enters into a speculative zone as the movie transforms into a lyrical vision of solitude, with the ubiquitous ocean embodying the entire community’s paradox sitting in their backyard — the portal to entire world stares at them, an expansive blue mirror that suggests potential and peril in equal doses.

“This is familiar turf for the director, whose short of the same name revolved around men sharing stories of their dramatic trips across the wave, as they discussed the allure of escape in near-spiritual terms. Beyond that — and a fleeting image of the vast ocean glimpsed from above — the feature-length Atlantics applies this notion to more traditional narrative beats, at least at first. As a local detective (Ibrahima Mbaye) begins tracking Ada around town in an attempt to solve the mystery of the blaze, Atlantics seems as though it’s heading into noir territory.

“Then it careens into a far more enticing labyrinth of enigmatic developments, including the possession of several local women by men who died at sea. Though it never becomes a horror movie, this ominous twist transforms the movie into dark poetry that exhumes the psychological duress experienced by Ada and the other women left behind by giving it a literal dimension. It’s an ambitious device that manages to inject the drama with an otherworldly urgency.

“Diop is a disciple of Claire Denis (as an actress, she appeared in Denis’ 35 Shots of Rum), and clearly aspires to the visual language at the heart of Denis’ talents. Atlantics is based in snippets of lonely vistas and dreamlike exchanges loaded with emotional ramifications. Cinematographer Claire Mathon (Stranger by the Lake) bathes scenes in heavy shadows and neon-blue hues that intensify the movie’s gripping atmosphere as Ada comes to terms with her missing partner and develops a new kind of empowerment with the women around her.

“With so much extraordinary imagery at every turn, Atlantics doesn’t always fuse its disparate ingredients into a gratifying narrative whole. The detective’s investigation has a forced quality at odds with the more introspective moments surrounding it, and Atlantics falls short of finding the payoff that its puzzle of a story hints at from the start. Instead, Diop lingers in a complex mood with the confidence of a purely cinematic storyteller.

“As it ventures further along its spellbinding path, Atlantics remains a deeply romantic work that magnetized the fears of people trapped by their surroundings and striving for the companionship that can rescue them from despair. It doesn’t quite let them get there, but Diop doesn’t strike a hopeless tone the whole way through. Ultimately, Atlantics shows how that even these bleak circumstances can have empowering ramifications for the women trapped by the shore, and why it’s a portal to a better life even if they stay put.”

NOVEMBER 15: Charlie’s Angels (dir. Elizabeth Banks) – Synopsis from the film’s official website: “Director Elizabeth Banks takes the helm as the next generation of fearless Charlie’s Angels take flight. In Banks’ bold vision, Sabina Wilson (Kristen Stewart), Elena Houghlin (Naomi Scott), and Jane Kano (Ella Balinska) are working for the mysterious Charles Townsend, whose security and investigative agency has expanded internationally. With the world’s smartest, bravest, and most highly trained women all over the globe, there are now teams of Angels guided by multiple Bosleys (Banks, Patrick Stewart, Djimon Hounsou) taking on the toughest jobs everywhere. The screenplay is by Elizabeth Banks from a story by Evan Spiliotopoulos and David Auburn.”

NOVEMBER 15 (NY/LA), NOVEMBER 19 (airing on HBO at 9:00 PM EST): Ernie & Joe: Crisis Cops (dir. Jenifer McShane) – DOC NYC synopsis: “In confrontations between law enforcement and the mentally ill, the consequences are often traumatic, if not deadly. Recognizing that police officers are frequently the first responders to incidents involving people with mental illness, the San Antonio Police Department has developed an innovative mental health unit to divert the mentally ill away from jail and into proper treatment. Ernie & Joe: Crisis Cops follows two officers in the unit, allowing audiences to witness firsthand how they de-escalate situations to help people in crisis.”

NOVEMBER 15: The Hottest August (dir. Brett Story) – BAM synopsis: “How do you feel about the future? That’s the question filmmaker Brett Story (The Prison in Twelve Landscapes) posed to dozens of New York City residents—from an Afrofuturist performance artist to stoner skateboarders to Hurricane Sandy survivors—during the sweltering summer of 2017. The answers she received reveal the deep-seated insecurities and anxieties underpinning life in an era when global warming and late-stage capitalism have seemingly set us on an apocalyptic path of no return. Balancing the engaging humanity of its subjects with an eerie science-fiction dread, The Hottest August is a funny, urgent, provocative, and visually mesmerizing look into our future as seen from the perilous present.”

NOVEMBER 15: The Incredible 25th Year of Mitzi Bearclaw (dir. Shelley Niro) – AMC Theatres synopsis: “On Mitzi Bearclaw’s (MorningStar Angeline) 25th birthday, she’s asked to come back home to her reserve from her life designing hats in downtown Toronto to see her sick mother. As Mitzi reconnects with the land, her family and the infinitely quirky residents of Owl Island, she grows from resentful and restless to reconnecting and embracing the charm of her home through encounters with three spirits. When your spiritual guides are space travelers and their enemies are apocalyptic soothsayers, it’s easy to keep your feet on the ground.”

NOVEMBER 15 (NY), DECEMBER 17 (VOD): Sequestrada (aka Arara or Tribe) (dirs. Sabrina McCormick and Soopum Sohn) – City Cinemas Village East Cinema synopsis: “Kamodjara (Kamodjara Xipaia) and her father, Cristiano, are members of an indigenous tribe that resides on an Amazonian reservation. When they leave their reservation to protest a dam that will displace their people, Kamodjara is separated from her family and kidnapped by traffickers. Roberto (Marcelo Olinto), an indigenous agency bureaucrat overseeing a report that could change everything, is under pressure to support dam construction. Thomas (Tim Blake Nelson), an American investor in the dam, makes his way to Brazil to sway Roberto’s opinion. Sequestrada tells the story of how these three lives intertwine in front of a backdrop of geopolitics and environmental disaster.”

NOVEMBER 15 (NY/LA): To Kid or Not to Kid (dir. Maxine Trump) – Cinema Village synopsis: “Filmmaker Maxine Trump turns the camera on herself and her close circle of family and friends as she confronts the idea of not having kids. While exploring the cultural pressures and harsh criticism childfree women regularly experience, as well as the personal impact this decision may have on her own relationship, Maxine meets other women reckoning with their choice: Megan, who struggles to get medical permission to undergo elective sterilization, and Victoria, who lives with the backlash of publicly acknowledging that she made a mistake when she had a child. To Kid or Not to Kid bravely plunges into an aspect of reproductive choice often misunderstood, mischaracterized, or considered too taboo to discuss. With rising public awareness about climate change, resource scarcity and global population, this timely film asks the question ‘Why can’t we talk about not having children?'”

NOVEMBER 15: The Warrior Queen of Jhansi (dir. Swati Bhise) – AMC Theatres synopsis: “The Warrior Queen of Jhansi tells the true historical story of the Rani (translation: Queen) of Jhansi, a feminist icon in India and a fearless, freedom fighter – a real-life Wonder Woman who earned a reputation as the Joan of Arc of the East when in 1857 India, as a 24-year old General, she led her people into battle against the British Empire. Her insurrection shifted the balance of power in the region and set in motion the demise of the notorious British East India Company and the beginning of the British Raj under Queen Victoria.”

NOVEMBER 19 (streaming on Hulu): Margaret Atwood: A Word After a Word After a Word Is Power (dirs. Nancy Lang and Peter Raymont) – Toronto International Film Festival synopsis: “Margaret Atwood is a household name. Millions of readers worldwide know her books cover to cover, but few know the woman behind these stories. For a year, directors Nancy Lang and Peter Raymont and their film crew kept pace with Atwood and her late partner, Graeme Gibson, as they travelled to speaking engagements, spent time with family, and visited the set of The Handmaid’s Tale, the wildly popular TV series adapted from Atwood’s 1985 novel. Her poetry and prose are brought to life through voiceovers from Tatiana Maslany, revealing the personal and societal factors that inform Atwood’s stories. With personal stories shared by friends, family, and Atwood herself, the film also explores her upbringing in the Canadian wilderness and her early years as a poet, and provides a rare glimpse into the writer’s practice as she completes the final chapters of her latest work, The Testaments.”

NOVEMBER 21 (streaming on Netflix): The Knight Before Christmas (dir. Monika Mitchell) – Polygon synopsis by Petrana Radulovic: “Netflix holiday specials already gave us modern day prince and princess switcheroos. The next logical, totally reasonable step in this progression: roping in some knights. But not just some modern stately officials from an imaginary tiny European country— nay! Netflix has decided to bring-eth a real bonafide medieval knight to bless Vanessa Hudgens’ holiday season.

“Enter The Knight Before Christmas! Because there’s that poem called ‘The Night Before Christmas’ and the guy in this movie is an actual knight? And it happens before and around Christmas? Genius!

“Regular ol’ science teacher Brooke (Vanessa Hudgens) finds a very confused man who talks like he’s a Medieval Times actor. Except, he’s actually from the medieval times. Brooke thinks Cole (Josh Whitehouse from ‘Poldark’) is just a regular amnesia patient, so against the judgement of literally everyone in her life, she decides to take him in for the holidays.

“Because this is a Christmas movie, the two bond, find joy in the holidays, and will most likely fall head over heels for each other by the time Dec. 25 rolls around. Expect wonderful, gooey, marshmallow-y fluff, perfect as an accompaniment to a mug of hot cocoa.”

NOVEMBER 22: A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood (dir. Marielle Heller) – TheWrap’s Toronto International Film Festival review by Steve Pond: “Fred Rogers, a Presbyterian minister from Pittsburgh better known simply as Mr. Rogers, is an unlikely movie star, and also an unlikely guy to be at the center of a movie. Mr. Rogers, after all, was the personification of niceness in a medium that prefers a little tension and conflict, a good guy who refuses to search for bad guys to tangle with.

“But Morgan Neville’s exceptional documentary Won’t You Be My Neighbor? solved the problem last year by finding the doubt and pain at the heart of Mr. Rogers’ niceness, and by showing how much his purposefully cheesy ‘Land of Make Believe’ in his long-running show ‘Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood’ was grappling with real world problems. And Marielle Heller’s A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood, which had its world premiere on Saturday night at the Toronto International Film Festival, takes the different approach of making Mr. Rogers the balm that helps heal a different troubled person, a magazine journalist badly in need of a shot of kindness.

“It might be the softest, slowest movie to play in Toronto this year — but those are perfectly apt choices to tell this story. A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood finds a gentle state of grace and shows the courage and smarts to stay in that zone, never rushing things or playing for drama.

“Make no mistake, there’s big drama here, as Matthew Rhys’ Lloyd Vogel — a slightly fictionalized version of Esquire journalist Tom Junod — is spurred by an interview with Fred Rogers to heal a stormy relationship with the philandering father who deserted the family when his wife fell ill.

“But just as Mr. Rogers used his show to talk about big issues with children in a tone that was softer and more halting than you’d expect given the subject matter, so does Heller stick to understatement in a way that threatens to become dull or sappy but never does. What she pulls off here is a small, sweet miracle of sorts.

“In her previous two films, Diary of a Teenage Girl and Can You Ever Forgive Me?, Heller proved to be a remarkably empathetic and understated director, with a knack for comedy in the stories of troubled people.

“And this film is indeed very funny, as investigative journalist Vogel chafes at the idea of a 400-word assignment to write about Rogers for a special issue devoted to heroes. And when his subject refuses to be bothered by tough questions, often as not thanking the writer for his insight, Vogel throws up his hands at the idea of getting a decent article out of it.

“There is, of course, a great article in it, though Vogel has to slowly realize that the real piece is about the way Mr. Rogers changes the life of an angry workaholic writer with a new baby at home and huge unresolved father issues of his own. (And the 400-word limit? Forget about it.)

“Rhys is strong as Vogel, but the attraction will no doubt be Tom Hanks as Mr. Rogers. It’s unlikely any other names were very high on Heller’s wish list, because Hanks is the only movie star with a niceness quotient to approach Mr. Rogers. Maybe that niceness has hurt him in recent years with awards voters (rather amazingly, Hanks, one of only two to win Best Actor Oscars in back-to-back years, hasn’t even been nominated since 2000). But it’s hard to imagine that his pitch-perfect channeling of Rogers’ magnificent and slightly unsettling calm won’t put him in the thick of a supporting-actor race that will probably be full of actors who could easily be considered co-leads, including Brad Pitt in Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood, Matt Damon in Ford v Ferrari and Anthony Hopkins in The Two Popes.

“Suffice it to say that tears were flowing onscreen and off at Roy Thomson Hall in Toronto. Maybe Mr. Rogers will be too soft for some moviegoers, but the box office success of the Won’t You Be My Neighbor? suggests that Sony could have a solid player in this lovely valentine to kindness at a time when that virtue is in desperately short supply around the world.”

NOVEMBER 22: Frozen 2 (dirs. Chris Buck and Jennifer Lee) – Disney Movies synopsis: “Why was Elsa born with magical powers? The answer is calling her and threatening her kingdom. Together with Anna, Kristoff, Olaf and Sven, she’ll set out on a dangerous but remarkable journey. In Frozen, Elsa feared her powers were too much for the world. In Frozen 2, she must hope they are enough. From the Academy Award®-winning team—directors Jennifer Lee and Chris Buck, producer Peter Del Vecho and songwriters Kristen Anderson-Lopez and Robert Lopez—and featuring the voices of Idina Menzel, Kristen Bell, Jonathan Groff and Josh Gad, Walt Disney Animation Studios’ Frozen 2 opens in U.S. theaters on Nov. 22, 2019.”

NOVEMBER 22 (in theaters), DECEMBER 6 (streaming on Apple TV+): Hala (dir. Minhal Baig) (DP: Carolina Costa) – Toronto International Film Festival synopsis by Cameron Bailey: “This breathtakingly assured feature from US writer-director Minhal Baig is about a teenager desperately searching for herself while straddling two very different worlds.

“The only child of Pakistani immigrants to the US, Hala (Geraldine Viswanathan) finds herself poised on the precipice of womanhood with no safety net in sight. Hala’s mother seems stiflingly traditional and overprotective, while her father seems more comfortable with a progressive world, encouraging Hala’s education and conversing with her in English instead of Urdu. The one matter on which both parents agree, however, is boys: Hala should have nothing to do with them until the time comes for her to enter into an arranged marriage.

“Yet Hala is hopelessly drawn to Jesse (Jack Kilmer), a classmate who shares her passion for skateboarding and literature. The two begin secretly meeting and Hala rapidly runs out of convincing alibis. The more Hala’s domestic life and social life clash, the more she begins to see her parents’ roles reverse — to the point where Hala discovers that she and her mother may just be able to empower each other.

“Baig’s maturity as a director is most evident in subtlety: her spare and elegant frames and the ease with which her characters move through them; the muted colour palette that fosters a sense of intimacy in scenes both tender and bracing. The performance Baig draws from Viswanathan is a thing of quiet beauty, awash in vulnerability and wonder. ‘Hala’ means ‘halo’ in Arabic, and while Baig’s heroine is no angel, she approaches her dilemma with something that can best be described as grace.”

NOVEMBER 22 (NY/LA): Shooting the Mafia (dir. Kim Longinotto) – Quad Cinema synopsis: “Sicilian photographer Letizia Battaglia began a lifelong battle with the Mafia when she first dared to point her camera at a brutally slain victim. A woman whose passions led her to abandon traditional family life and become a photojournalist in the 1970s—the first female photographer to be employed by an Italian daily newspaper—Battaglia found herself on the front lines during one of the bloodiest chapters in Italy’s recent history. She fearlessly and artfully captured everyday Sicilian life—from weddings and funerals to the grisly murders of ordinary citizens—to tell the narrative of how the community she loved in her native Palermo was forced into silence by the Cosa Nostra. Weaving together Battaglia’s striking black-and-white photographs, rare archival footage, classic Italian films, and the now 84-year-old’s own memories, Shooting the Mafia paints a portrait of a remarkable woman whose bravery and defiance helped expose the Mafia’s brutal crimes.”

NOVEMBER 22 (NY): Varda by Agnès (dir. Agnès Varda) (DPs: François Décréau, Claire Duguet and Julia Fabry) – Film Forum synopsis: “This final film from the beloved Oscar®-winning Agnès Varda (1928 – 2019) is a characteristically playful, profound, and personal summation of the director’s own brilliant career. At once impish and wise, she acts as our spirit guide on a free-associative tour through her six-decade artistic journey, shedding new light on her films, photography, and recent installation works while offering her one-of-a-kind reflections on everything from filmmaking to feminism to aging. Suffused with the people, places, and things she loved—Jacques Demy, cats, colors, beaches, heart-shaped potatoes—this wonderfully idiosyncratic work of imaginative autobiography is a warmly human, touchingly bittersweet parting gift from one of cinema’s most luminous talents.”

NOVEMBER 27: Queen & Slim (dir. Melina Matsoukas) – Synopsis from the film’s official website: “From two-time Grammy award winning director Melina Matsoukas, the visionary filmmaker behind this generation’s most powerful pop-culture experiences, including HBO’s ‘Insecure,’ the Emmy award-winning ‘Thanksgiving’ episode of Netflix’s ‘Master of None,’ and Beyoncé’s ‘Formation,’ and from trailblazing, Emmy-winning writer Lena Waithe (Netflix’s ‘Master of None’), comes the unflinching new drama, Queen & Slim.

“While on a forgettable first date together in Ohio, a black man (Get Out’s Daniel Kaluuya) and a black woman (Jodie Turner-Smith, in her first starring feature-film role), are pulled over for a minor traffic infraction. The situation escalates, with sudden and tragic results, when the man kills the police officer in self-defense. Terrified and in fear for their lives, the man, a retail employee, and the woman, a criminal defense lawyer, are forced to go on the run. But the incident is captured on video and goes viral, and the couple unwittingly become a symbol of trauma, terror, grief and pain for people across the country.

“As they drive, these two unlikely fugitives will discover themselves and each other in the most dire and desperate of circumstances and will forge a deep and powerful love that will reveal their shared humanity and shape the rest of their lives.

“Joining a legacy of films such Set It Off and Thelma & Louise, Queen & Slim is a powerful, consciousness-raising love story that confronts the staggering human toll of racism and the life-shattering price of violence.”

NOVEMBER 27: 63 Up (dir. Michael Apted) (many DPs, including Shana Hagan) – Film Forum synopsis: “Michael Apted’s landmark longitudinal documentary series, beginning in 1963, has followed the lives of a dozen or so British 7-year-olds, checking in with them every seven years. There’s scrappy Tony, a jockey-turned-cabbie; the terribly posh public school boys who become fox-hunting, aristocratic barristers; three working-class little girls for whom marriage, divorce, and children define much of their lives (one of whom has the temerity to confront Apted for his sexism). The British class system plays a major role, but so too do luck and temperament, romance, religion, mental illness, and race. Apted subtly collages historical footage, allowing his subjects to fast-forward into the person they become, much as flowers bud, bloom and fade — allowing us to consider our own life cycle with startling and poignant clarity.”

NOVEMBER 29: The Body Remembers When the World Broke Open (dirs. Kathleen Hepburn and Elle-Máijá Tailfeathers) – Another Gaze’s Toronto International Film Festival review by Esmé Hogeveen: “Elle-Máijá Tailfeathers and Kathleen Hepburn’s The Body Remembers When the World Broke Open follows a day in the life of two women: Áila and Rosie. These characters meet on a street in Vancouver, Canada: Áila (Tailfeathers) is on her way home from work when she sees the pregnant Rosie (Violet Nelson), barefoot and bruised, walking away from her abusive partner’s home. Áila offers Rosie support, inviting her back to her apartment for a moment of respite and a change of dry clothes. There the women speak and discover sources of connection and dissonance. Frequent silences and moments of awkwardness underline the challenge of accepting that support may necessarily involve mutual vulnerability.

“A TV Guide summary of The Body Remembers would probably describe it as two women grappling with the complexity of domestic abuse, likely also noting that the protagonists come from different Indigenous backgrounds. This kind of synopsis would be true, yet conjures clichéd narratives of drama, trauma, and racial and cultural identity that the film avoids. Instead, Tailfeathers and Hepburn give us a grounded interrogation of these topics. Their script, along with Norm Li’s cinematography, focuses on the presence of violence as a pervasive aspect of female experience. Tensions arise from day-to-day dilemmas, such as the decision Rosie faces about whether to maintain the fraught stability of partnership, and to continue living with her partner’s mother, versus striking off on her own and facing as-yet unknown difficulties. With refreshing subtlety, Tailfeathers and Hepburn manage to show and not tell trauma. Their nuanced approach is particularly felt in the film’s andante pacing – The Body Remembers is slow. Much of the story is told in real time with scenes and shots alternating between Áila’s and Rosie’s perspectives. As viewers, the stripped-down narrative of The Body Remembers encourages us to feel close to both women, but the absence of a melodramatic arc prevents us from assuming we can fully understand them. In lieu of a smooth catharsis, we are compelled to note the ways in which individuals may protect themselves through shielding secrets and intimacies.

“Taken as a whole, The Body Remembers is a thoughtful illustration of the complex ways in which trauma can educate, undermine, and fortify an individual’s sense of self and her knowledge about the world. In a scene that comes late in the film, Áila halfway convinces Rosie to go to a safe house and the characters ride there together in a cab. At first the atmosphere in the car is tense. Rosie is clearly unsure of the short- and long-term advantages of staying in a shelter. The characters’ hitherto smooth rapport becomes uneasy as Áila shifts from empathetic first-responder to assertively – though never aggressively – suggesting ways for Rosie to alter her circumstances. The viewer is placed in the uncomfortable position of pseudo-arbiter: we observe Rosie’s desire to be independent alongside her difficult position, as well as Áila’s own vulnerability, a force which underlies her desire to support Rosie. Without knowing the entirety of either woman’s situation, judgment seems impossible: throughout the film, would-be assessments about the characters’ decisions flip self-reflexively onto the viewer. Who are we to assess the righteousness of Áila’s advice, or what course of action would best serve Rosie? What is the relationship between receiving support and consenting to it? Rosie never asks Áila for help, at least not verbally, and in a few scenes she wryly queries Áila’s impulse to assist her. In the cab, Rosie somewhat cheekily convinces the driver that she and Áila are sisters and that Áila is en route to alcohol addiction treatment. The cabbie’s fumbling kindliness, including admission of his own addiction struggles, furthers the loose promise of connections between strangers initially presented by Rosie and Áila’s encounter. At the same time, the unlikeliness of these interchanges leading to any sort of systemic change underscores the unstable social realities impacting all the characters’ lives. While the women are paying customers, the driver displays compassion, but would he even notice them, let alone their challenges, outside of a transaction? While Rosie’s sense of humour in this scene has a kind of optimistic potential in that it leads to a sharing of issues, it also serves as a reminder that identifying intersections between social issues doesn’t necessarily bring us any closer to solving the underlying problems.

“When watching The Body Remembers, we are constantly reminded of our limited understanding of the characters. That the women’s backgrounds are relatable, yet widely different – Áila is Blackfoot from the Kainai First Nation (Blood Reserve) in Canada and Sámi from northern Norway, whereas Rosie is Kwakwaka’wakw from British Columbia, Canada – reiterates the difficulty of mapping one experience or perspective onto another. Beyond differences in heritage, Áila and Rosie also occupy disparate class positions: Áila keeps a small, chic apartment, whereas Rosie stays with her boyfriend’s mother in a seemingly less upscale part of Vancouver. We only see the characters for part of a single day, and the script lacks voiceover or other extra-expositional devices. Perhaps this psychic distance is what makes the camera’s intimate physical proximity so affecting. An early scene in a doctor’s office, where Áila changes out of her clothes in preparation for an IUD insertion, is echoed when the camera tracks Rosie as she tugs off a rain-drenched tie-dye sweatshirt and changes into borrowed clothes in Áila’s bathroom. This borderline voyeurism recalls the ambiguous lines between caregiving, advocacy, charity, and presumption. An additional layer of complexity is added to the protagonists’ dynamic through their different relationships to motherhood: whereas Rosie seems relatively calm about her pregnancy, Áila has a more uncertain position on maternity and mentions at one point that her partner may be more interested in parenting than she presently is.

“The Body Remembers is aware of its limits, and this lends a directness to its storytelling. The production is sparse and tactfully avoids fanciful flashback sequences or camera flourishes. I also noted an apt absence of sentimentality about landscape. (Canadian television and film projects about Indigenous characters or topics helmed by non-Indigenous makers seem often to use scenic establishing shots as shorthand for establishing identity and place.) Instead, the film is set in a close and highly contained urban, human sphere. Shots roil with intensity, beckoning the viewer in. There are no moralizing shortcuts or incentives for passing premature judgment. By thoughtfully abstaining from manufactured catharsis or generalisations about womanly bonds or trauma, The Body Remembers centres the vast challenges inherent to interpersonal recognition and support. Read in this light, the film’s andante rhythms make all the more sense. Tailfeathers and Hepburn disavow spectacle to offer humane glimpses, chronicling the insidious presence of trauma.”

NOVEMBER 29: Cavale (aka Girls on the Run) (dir. Virginie Gourmel) (DP: Juliette Van Dormael) – Cineuropa’s Brussels International Film Festival review by Aurore Engelen (translated from French): “Kathy, a secretive and rebellious teenager, has only one goal in mind: to escape the psychiatric institution where she has been locked up. Soon, she runs away and returns to her father, the only one who can free her from ‘this prison.’ Against all expectations, her roommates Nabila and Carole, crazy and weird in equal measures, invite themselves to her improvised escape. But nothing will happen as planned…

“After Stagman and Aïe, two short films set in worlds of fantasy, Virginie Gourmel has come together with Micha Wald (Horse Thieves, Simon Konianski), who penned the script, to retrace the route of Kathy, a fragile young girl without guidance who seeks to rewrite her own story by all means necessary. On her path, she meets two other lonely girls, Nabila and Carole, just as lost as she is. All three will rely on one another, but what kind of support can they really hope for from such unsteady reinforcements?

“In her first two films, Virginie Gourmel was interested in monsters whose deformity was visible: a vampire and a deer-man, characters on the margins, different, damaged by life. With Cavale, selected in National Competition at the Brussels International Film Festival, she slides into the real by playing with characters whose monstrosity is completely internal: freaks, slightly crazy and heavily medicated young people, agitated adolescents.

“At the hospital, Kathy rebels, refuses her pills, rejects the ‘protection’ decided by the judge. And the girls wonder about their mental health. Once the hospital walls behind them, the film turns into a road movie. A real initiatory journey for Kathy, Nabila and Carole. In a ‘family I hate you’ fashion, the three inseparable girls, by force of circumstance, discover friendship, betrayal, and first love, like an accelerated adolescence — until the slip up. The trio becomes a duo when Kathy crosses the path of her little brother…

“The film, told from the perspective of the young girls, is carried by three young actresses in their first film roles: Lisa Viance, Yamina Zaghouani and Noa Pellizari. Though Cavale does not reinvent the road movie format, nor that of the coming of age film, the film succeeds, in a few gracious scenes, to embody female adolescence. In shooting the relationship to the body of three young girls caught in a moral and hormonal storm, trying clumsily but with great energy to find answers to the questions that torment them, Virginie Gourmel offers a multifaceted portrait of this ever so ephemeral period, all the while questioning our rapport to madness.

“The cinematography is handled by Juliette Van Dormael (Angel), a young woman in high demand these days who has just shot Frédéric Fonteyne’s Filles de Joie (previously known as La Frontière). The work on colours, in particular, and on set-design, gives power to the three young girls’ escape.”

NOVEMBER 29: My Friend the Polish Girl (dirs. Ewa Banaszkiewicz and Mateusz Dymek) – The Guardian review by Peter Bradshaw: “Here is a low-budget experiment in metafiction, or quasi-fiction, with a shimmer of anxiety, shot mostly in black and white with periodic excursions into color and animation – all about a young Polish woman living alone in a London flat, dealing with issues that are never clearly articulated. It often seems like nothing so much as a postmodern, 21st-century version of Polanski’s classic Repulsion.

“The film itself appears to be a faux video diary by a (fictional) independent film-maker, recounting her experiences making a documentary about the life of a migrant worker in London. Emma Friedman-Cohen plays Katie, the director, and Aneta Piotrowska gives a bold and interesting performance as Alicja, the Polish woman and part-time actor Katie finds through an audition process. Alicja allows Katie into her life, at least partly through loneliness, and seems intensely sexual in a compulsive and troubled way. (An actor friend playfully addresses her as ‘Stella!’ from A Streetcar Named Desire.) Katie comes to believe that Alicja might have been abused as a child; she is partly excited by the thought that her film might be on the verge of a revelation but also frightened by the intensity and responsibility that that would entail.

“My Friend the Polish Girl is a fiction about an imagined factual film, and yet it is apparently so rooted in an exploratory, improvisatory process, that it seems almost a real-time documentary about actors immersing themselves in roles inspired by their own feelings. The result is not perfect, but by the end of the film you find yourself caring about Alicja, about what has brought her to this stage and what is to become of her.

“In its indirect way, it casts a compassionate light on London’s migrant workers that a more conventional documentary – or conventional drama – wouldn’t.”

NOVEMBER 29 (NY): Ximei (dirs. Andy Cohen and Gaylen Ross) – Cinema Village synopsis: “Ximei is a young woman from China’s rural Henan Province who contracted AIDS when the government encouraged impoverished villagers in the late 1990’s to sell their blood plasma for money, literally bleeding people for profit. Unsanitary conditions and lack of screening for disease, caused blood infected by the HIV virus to be transmitted to donors and then to the recipients of blood transfusions. A million Chinese citizens were infected with HIV and countless persons died from AIDS. Thousands of peasants still suffer the consequences, their plight hidden from the eyes of the world and strongly censored by Chinese authorities. Ximei has dedicated herself to revealing the desperate conditions that continue to exist among her fellow AIDS patients, the discrimination, and the lack of clinics, and medical treatments available to them. Even now officials try to terrorize Ximei into silence, closing down her halfway house for AIDS patients, while she single-handedly fights for their social and legal rights. Her courageous actions and fiery character transform their tragedy into lives of hope and dignity.”