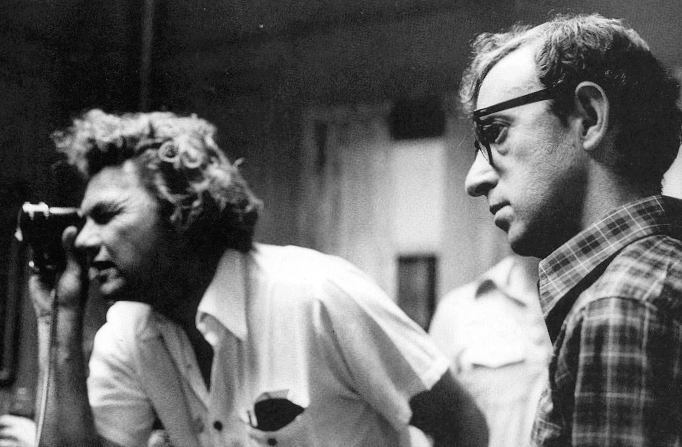

After watching the endlessly strange and fascinating drama Bad Lieutenant recently, I knew I had to see some more of controversial director Abel Ferrara’s work. On the surface, Ms .45 is just another exploitation flick from its era, a post-Death Wish/Taxi Driver rape revenge story intended to trade on the sick pleasures of watching a female victim of sexual violence punish all men for the sins of a few. And the film is certainly the product of testosterone-driven artists; it was written (Nicholas St. John), directed (Abel Ferrara), photographed (James Lemmo), edited (Christopher Andrews) and scored (Joe Delia) by men. Despite those details, it can be argued there would be no Ms .45 without the lead performance of Zoë Lund, then an eighteen-year-old Columbia University student making her feature film debut.

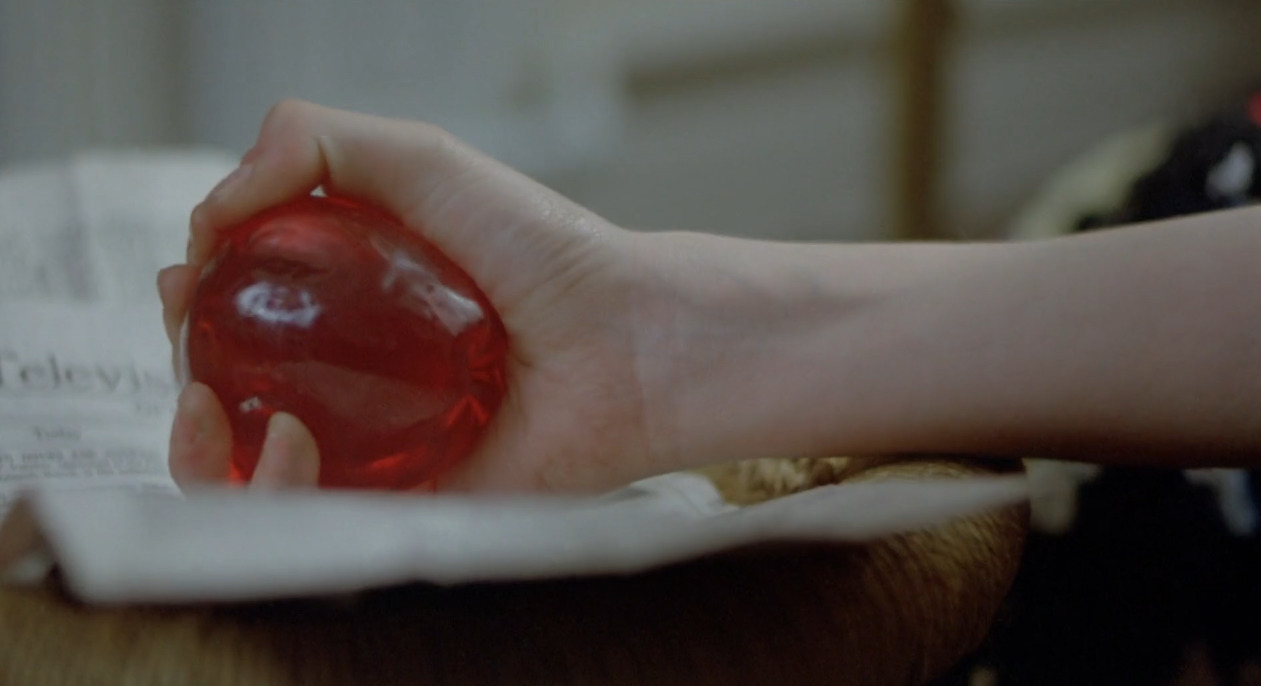

Lund, known at the time by her birth name Zoë Tamerlis, portrays Thana, a mute woman who is employed as a seamstress in Manhattan’s Garment Center neighborhood. On a sunny afternoon, while returning home from her job, she is sexually assaulted twice; first, by a man in a mask (played by Abel Ferrara) who pulls her into an alley, and then by a robber who had broken into her apartment sometime earlier and lay in wait until Thana opened her door. Already traumatized by the previous attack, Thana kills the second offender by bludgeoning him in the head with a paperweight. In a daze, Thana methodically dismembers the rapist’s corpse, lining her fridge with garbage bags full of body parts. Crucially, Thana takes possession of the man’s gun, hiding it in her purse for daily protection on the city streets.

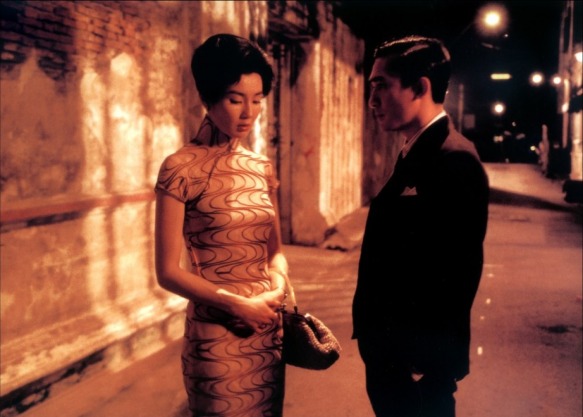

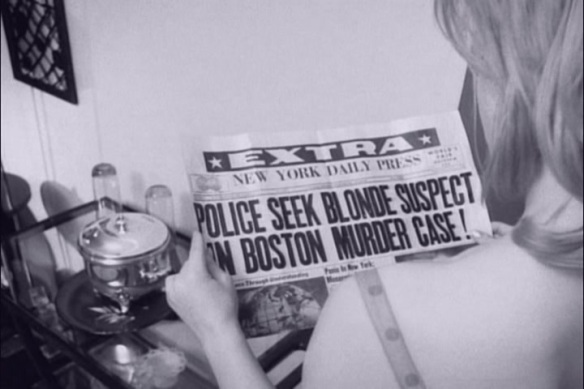

The gun changes everything about Thana. She transforms from a shy introvert to a vigilante serial killer of men, not only those who catcall her or try to assault her but also citizens who have committed no crime other than being male. Thana’s new identity gives her a voice she never had before, and she adjusts her physical appearance accordingly by wearing heavy makeup and fashionable outfits and by putting her hair up in an efficient ponytail. Aided by her more glamorous image, Thana lures her prey to their deaths in various scenarios; her power is fueled by the sorrow and anger of every woman who has been objectified and hurt by men.

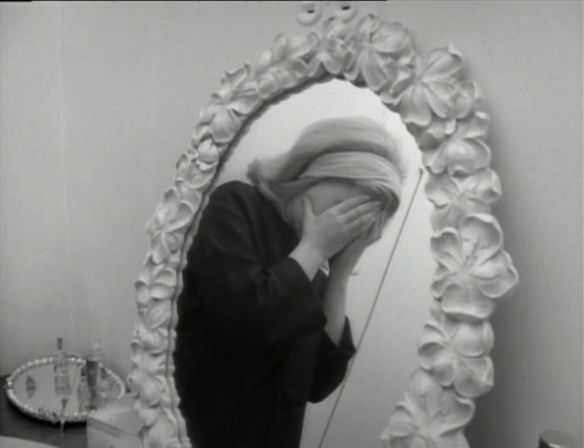

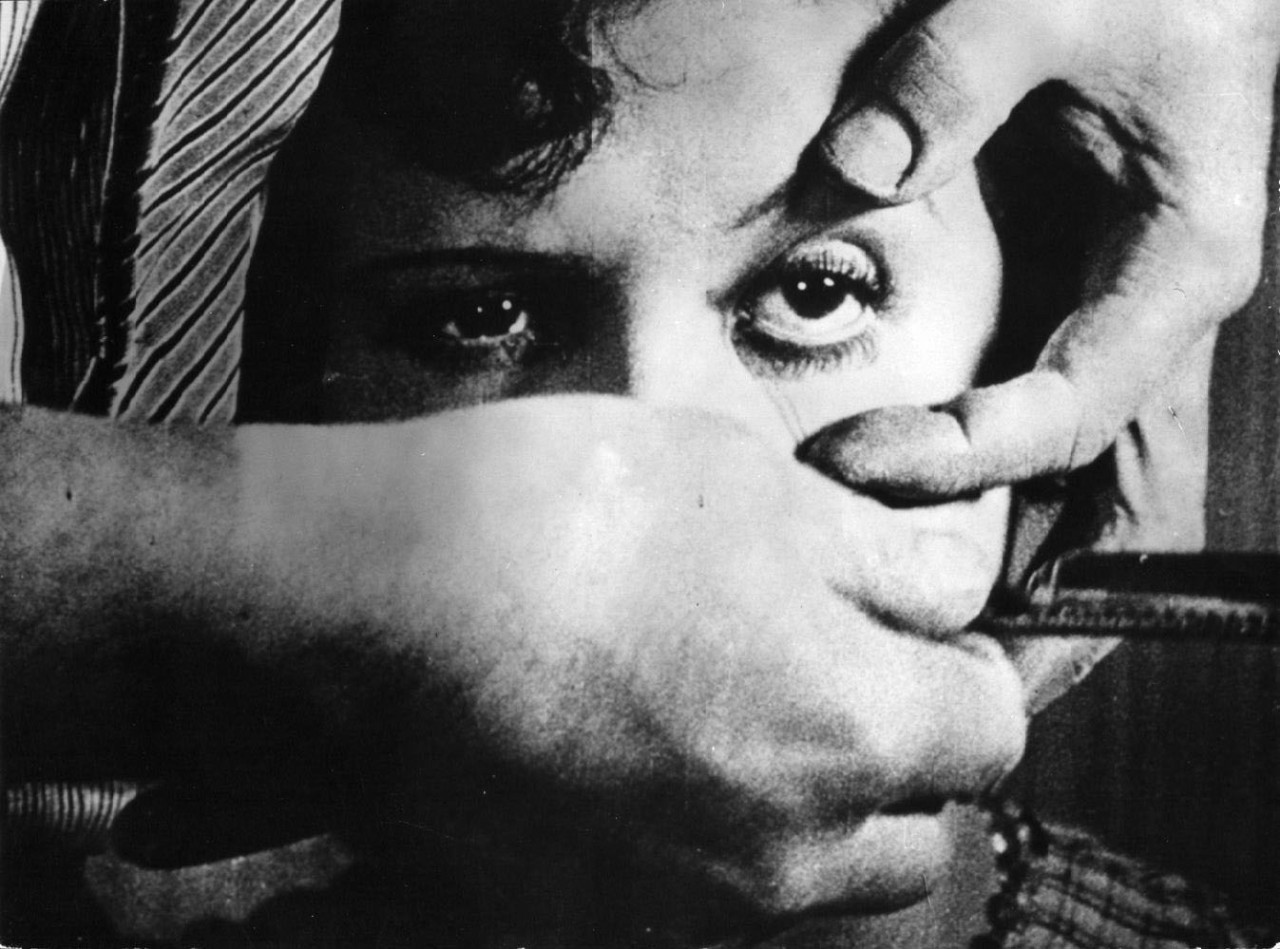

It’s hard to say whether this tale of retribution has a moral at the end or not, although the film concludes with a final scene that wraps up its grim narrative on an unexpectedly light note. Determining whether Ms .45 is a feminist film seems like a moot point since that’s not a term I would use to describe Abel Ferrara, based on the comments I’ve heard him make about Lund and other actresses in interviews – the jury’s still out on screenwriter Nicholas St. John, although I assume his views on women were somewhat similar since he had been friends with Ferrara since high school – but ultimately the film would not have the impact that it has without Zoë Tamerlis Lund as its star. You can never look away from her. She commands every frame with her bright green eyes and with her believable development into a single-minded assassin. Late in the film, Lund has her most memorable moment when Thana dons a nun’s habit and bright red lipstick for a Halloween party being thrown by her handsy boss; the poses that Thana assumes as she looks in a mirror and aims her revolver like a big-screen sharpshooter are chillingly reminiscent of Robert De Niro as Travis Bickle. Like the Greek mythological figure that Thana is linked to by name symbolism – Thanatos, god of death – there is a larger-than-life aura surrounding her ability to destroy the male population of New York City.

Research tells me that Zoë Lund was a polyglot, a prolific writer and an accomplished musician/composer, in addition to being the daughter of renowned sculptor Barbara Lekberg. Was Ms .45 to blame for Lund’s decision to abandon her privileged upbringing and education, temporarily move to Europe and become a heroin addict, the last of which defined her existence until her drug-related death in 1999? I don’t know; maybe the path she traveled was one she would have found regardless of a cinematic career. Perhaps there will never be a neat, sensible answer to the question. What remains indisputable, however, is that Lund elevates Ms .45 into something more than a portrait of New York City at its scuzziest. As difficult as the film may be to watch due to its frank themes, it is consistently engaging, a thought-provoking study of how rape and PTSD can alter a woman in unimaginable ways and reshape her concept of herself within society.