Angel (aka Danny Boy) (1982) – dir. Neil Jordan

Starring: Stephen Rea, Honor Heffernan, Marie Kean, Ray McAnally, Donal McCann, Veronica Quilligan, Peter Caffrey, Sorcha Cusack, Lise Ann McLaughlin, Macrea Clarke

Cinematography: Chris Menges

Angel (aka Danny Boy) (1982) – dir. Neil Jordan

Starring: Stephen Rea, Honor Heffernan, Marie Kean, Ray McAnally, Donal McCann, Veronica Quilligan, Peter Caffrey, Sorcha Cusack, Lise Ann McLaughlin, Macrea Clarke

Cinematography: Chris Menges

I am currently working my way through Neil Jordan’s filmography, as I often like to do with directors in order to get a sense of the bigger picture, studying the arcs that their careers travel. Two weeks ago I watched one of Jordan’s most famous films, The Crying Game (1992), for the first time.

(Warning: spoilers ahead. Proceed at your own risk if you have not seen the film.)

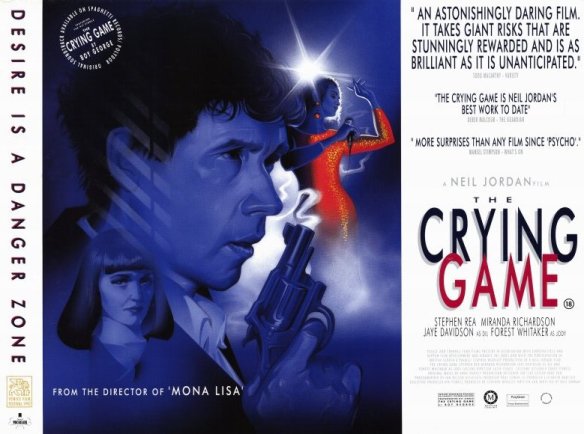

The Crying Game is a film that challenges our perceptions of masculinity and femininity, how first impressions and assumptions based on conventional thinking can shift and adapt in unexpected ways. Jordan implores us to look beyond the surfaces of characters and reach deeper understandings about human nature, the possibilities of emotional maturity and our capacity to express love despite obstacles both tangible and intangible. I am going to take a closer look at a few scenes from the film – not everything, of course, but just some sequences that inspire me.

I love the film’s opening credits. Line by line, the lyrics of Percy Sledge’s “When a Man Loves a Woman” fit the narrative perfectly. The opening scenes also establish the cross-section of major themes in the film: politics/national identity, race relations and sexuality. The kidnapping of British soldier Jody (Forest Whitaker) by an IRA faction headed by Fergus (Stephen Rea) and Jude (Miranda Richardson) sets up a series of parallels for the main characters (and us, the viewers) to question – Northern Irish vs. English, white vs. black, and eventually, when sexual identity becomes a focal point, straight/cisgender vs. not-straight/transgender (and other variations on the LGBT spectrum) – and how the complexities of these relationships transform the characters. Above all, The Crying Game is about how the two main characters achieve harmony within their individual minds and bodies, then how the passion they feel for one another blossoms into a lasting attachment.

One of the key moments at the beginning of The Crying Game, after Jody has been abducted and he is held for ransom, is when he befriends Fergus, the kindest of the captors. This scene, in which Fergus shows Jody the small kindness of allowing him to eat, is one of the first moments when the viewer realizes that the film is more than a thriller; on that genre level of the narrative, the fact that Jody has seen Fergus’s face represents a threat to the IRA group’s activities, but the idea that Jody remembers Fergus as “the handsome one,” having catalogued the details of his “killer smile” and other physical attributes, is an indication (not the first, but a strong one) that these characters are not who they initially seem to be. Every phrase – including “my pleasure” – is charged with meaning.

When Fergus removes Jody’s hood, it is as important a reveal as the famous “twist” that happens midway through the film. (More on that soon.) Neil Jordan prolongs the moment in a shot of Fergus that is filmed almost in slow motion, giving a simple action the appearance of something more, even though we don’t know exactly what yet.

Continuing in that same scene, Jody shows Fergus a photograph of his girlfriend Dil (Jaye Davidson), which prompts Fergus to make the comment that Dil would be “anybody’s type.” (When Fergus leans down to Jody, the camera tilts slightly to create a canted angle, an oft-used technique in the film to suggest that the bonds between men and women, as well as among men, are off-kilter.) The universality of Fergus’s claim will later test his preconceived notions about his relationship to sexuality, romance and love when, after Jody is killed by in a government raid on the hideout, Fergus escapes to London and tracks Dil down, bound to a promise he made to Jody that Dil would be looked after.

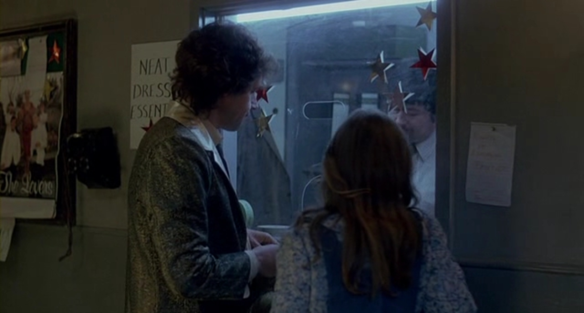

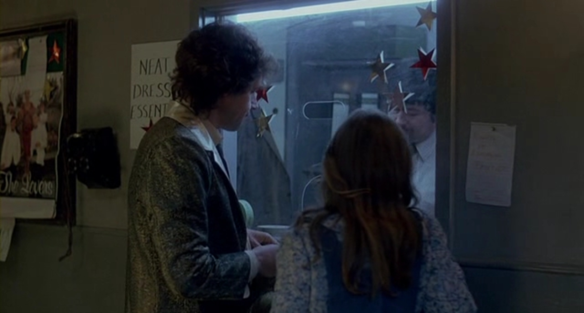

The first scene with Dil, when Fergus visits the hair salon where she works, establishes instant chemistry between the two characters. You know from Fergus’s first glance at Dil in real life that he is hooked, completely infatuated. This scene contains possibly my favorite image in the film: identity, sensuality and, considering the scissors, a violent act that destroys and then transforms a person into someone else – all in one shot of Jaye Davidson cutting Stephen Rea’s hair.

The shining, sparkling highlight of the film is when Dil – wearing a gold dress designed by Sandy Powell – lipsyncs to a cover of “The Crying Game,” the song that inspired the film’s title. The lyrics’ story is told by a narrator who is tired of relationships that initially seem like wonderful romances but are eventually revealed to be built on lies; in The Crying Game, the main characters’ secrets and lies are a constant source of conflict.

I especially love the way Neil Jordan wrote Dil’s singing scene in the screenplay: “Fergus looks up. Close-up of Dil’s hand, as music begins, making movements to the music. We see Dil, standing on a stage, swaying slightly. She seems a little drunk. She mimes to the song. She mouths the words so perfectly and the voice on the song is so feminine that there is no way of knowing who is doing the singing. She does all sorts of strange movements, as if she is drawing moonbeams with her hands.”

If The Crying Game is a film about people who continually push their (and others’) limits, then a perfect example is the scene in which Fergus and Dil share their first kiss. As the poster at the top of this page says, “desire is a danger zone”; when Fergus and Dil kiss, there is a kind of suspense as you wait to see what will happen next.

Soon afterwards, Fergus discovers a truth about Dil which is often described as “the twist” or “the secret” of the film: she has a penis. Back in 1992, many viewers were surprised by this revelation, so convincing was Jaye Davidson in the role. Dil is often mistakenly referred to as a transvestite, but if you have seen the film, you would agree that she is a transgender woman; she wears clothing not for preference but for necessity. She lives her life as a woman and dresses according to her gender, not her biological sex. That Fergus initially reacts with horror and revulsion when viewing Dil’s genitalia makes sense when one considers his background; for a man from in Northern Ireland, long before the comparatively modern climate of the early 90s, his belief in heteronormativity must have been ingrained in his upbringing. In this crucial encounter between Fergus and Dil, the presence of a penis seems to negate her status as a woman because that is the only way he can process the information in the moment. (My assumption was that Dil had not had sex reassignment surgery because she didn’t have much money, and that if she could afford it, she would do it – the film puts emphasis on her wish to embody womanliness physically as well as in spirit.) What matters even more in the film is that Fergus does not ultimately stop loving Dil; as the plot progresses, he kisses her again, he touches her body again. The connection between the two transcends everything he thought he knew about himself and about human sexuality.

(Incidentally: it should be noted that the “twist” was ruined for some people by the fact that Jaye Davidson was nominated for the Best Supporting Actor Oscar at the 1993 ceremony.)

Fergus’s former associate, Jude, follows him to London and blackmails him into helping her with another act of political violence. Again there is a canted angle and there is a twist on male-female interaction: Jude is the aggressor and Fergus is the unwilling object of affection. Like Fergus, Jude has also altered her hairstyle, but instead of shedding layers, she has switched to a ‘do that makes her look like a femme fatale from a film noir.

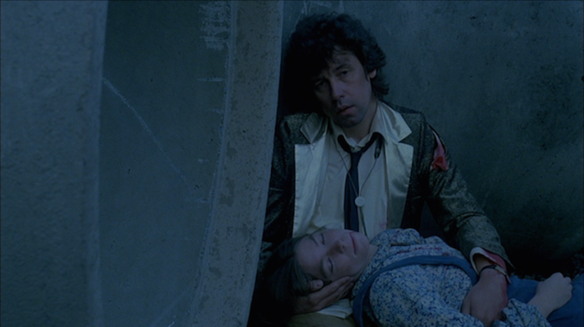

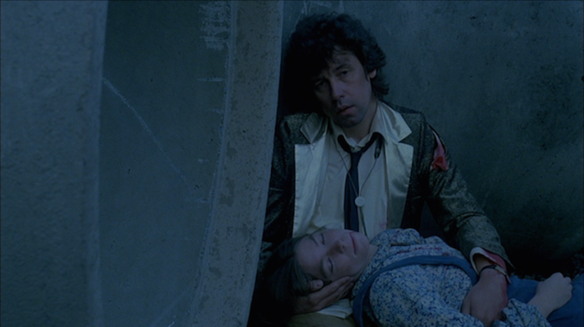

The last scene that I want to discuss is the moment when Fergus, in a role reversal, cuts Dil’s hair. As Neil Jordan asks throughout the film: what does it mean to lead a double life? In Fergus’s case, he has his recent past as Fergus, the terrorist accomplice, and his current life as “Jimmy,” the construction worker with no political ties; Dil is psychologically female and she dresses as a woman but she has male genitalia; Jody revealed himself to be smarter, funnier and more complicated than the man we thought we knew in the film’s first scenes. In this specific scene, Fergus cuts Dil’s hair because he plans on disguising her as a man in order to more effectively hide her from Jude; Dil does not know why Fergus is changing her appearance, however, nor does she know that Fergus was responsible for Jody’s death. The relationship is still weighed down by lies and omitted truths.

Another fascinating part of Fergus’s certainty that Dil’s survival depends on her presenting herself in public as a man is linked to his memories of Jody. In a way, Fergus is just as obsessed with Jody as he is with Dil. Throughout the film, we see Fergus visualize Jody wearing his cricket-playing outfit in happier times; you could say that The Crying Game is a story about a love triangle, even though one leg of the triangle is a ghost. Fergus redesigns Dil’s looks based on Jody’s appearance, so much so that the final touch is Dil wearing Jody’s old cricket uniform. Where does Fergus’s guilt end and his genuine feelings for Dil begin? As the film hurtles towards its conclusion, you see the ramifications of Fergus’s, Dil’s and Jude’s dangerous decisions. And in the end, you see that the real “twist” in The Crying Game isn’t the “shocking” nudity shown in the middle of the film: it’s that this couple’s tale actually has a happy ending, albeit an unusual one.

Two other films that I have seen in the past week also fit the theme of this post. Guinevere (1999, dir. Audrey Wells) puts Stephen Rea in the positions of observer and sort-of-predator once again, catching the eye of a beautiful woman (Sarah Polley) and convincing her of her own value; the difference here is that Rea is the seducer rather than the seduced. Kenneth Turan summed up the introduction to Rea’s character neatly in the Los Angeles Times review of Guinevere: “Though he’s working today as the wedding photographer, Connie, as everyone calls him, proves to be exactly what his appearance advertises: the grand artiste with the looks and the loft to complete the package. Unshaven, with unruly hair and a white scarf knotted casually around his neck, he is Mr. Irish Bedroom Eyes, and when we find out that he drinks whiskey straight and listens to cool jazz far into the night, it merely completes the picture.” None of this is to say that Guinevere compares favorably to The Crying Game, but I do wonder if Stephen Rea ever would have had a career as a romantic leading man if not for Neil Jordan’s massively successful film.

(By the way, I’ve noticed that the white scarf is a recurring motif for Rea: he wore a similar one in the 1994 film Angie and also when he received an award from the Irish Film & Television Academy for the mini-series “The Honourable Woman” in 2015.)

The second film that deserves mention is Stargate (1994), but before I write about it, I have to put the film in context with this interview of Jaye Davidson from 1993. He rejected the allure of fame and the notoriety that went with it. He acted in only one other feature film, the sci-fi adventure Stargate, reportedly because he asked for a million-dollar paycheck to play the villain, Ra. Nowadays, when so many young stars take advantage of social media platforms like Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr and Snapchat to connect with family, friends, fans and the press, it would probably be considered unthinkable for an overnight sensation to avoid the limelight. Times certainly have changed in 25 years.

So, then, we get to Stargate. Is it fair to compare Jaye Davidson’s performance as a one-dimensional alien antagonist with his work as Dil in The Crying Game? Without delving too deep into Stargate’s plot: a bunch of humans travel to another galaxy and they have to save an extraterrestrial civilization from its evil overlord, Ra (Davidson), who introduces himself to the group of earthlings only after shedding a gigantic mask, perhaps in a sort of homage to his role in The Crying Game. The New York Times film critic Caryn James wrote that Davidson makes “a suitably divine entrance. Mr. Davidson’s hair is in a long braid, and his costumes include a golden breastplate and flowing robes. His voice is electronically enhanced to give it a godlike rumble and on occasion the whites of his eyes are enhanced, too. There isn’t much acting involved. Mr. Davidson may not have wide-ranging career possibilities, but he makes the perfect Ra mannequin.” James’s review made me think twice about Davidson’s abilities as an actor, but only for about a second. Yes, physical appearance and appeal account for something, but they’re not everything. I don’t believe that anyone would care about his performance in The Crying Game if he hadn’t been more than a pretty face; it’s because he did a fantastic job as an actor that his work in that film still matters and why Stargate can’t be discredited either.

Ra’s series of threats against the film’s hero, Egyptologist/linguist Daniel (James Spader), provide us with my other favorite scene with Davidson in Stargate. Again, you could argue that the bulk of his acting in this film stems from sneering, but it’s enjoyable all the same.

Right after I watched Stargate, I found a Digital Spy article about Jaye Davidson that was written mere hours earlier. Proving that every story can have a twist when you least expect it, Davidson has apparently joined Twitter as of early January (I wonder if it was a New Year’s resolution?). Obviously social media has developed in ways that no one could have imagined a quarter-century ago, and you figure that the Jaye Davidson of 1992-1994 would have laughed hysterically at the concept of Twitter, but it’s interesting that after making the choice to abandon a life of celebrity and subsequently experience total anonymity for decades, Jaye Davidson has evidently come to terms with his brief but incredible history as an actor and he has joined the world of selfie-sharing to which so many of us now belong. Wonders never cease, do they?

Director Ceyda Torun with some of the stars of her new documentary, Kedi.

Here are nine new movies due to be released in theaters this January, all of which have been directed and/or photographed by women. These titles are sure to intrigue cinephiles and also provoke meaningful discussions on the film world, as well as the world in general.

JANUARY 6: Underworld: Blood Wars (dir. Anna Foerster) – Sony Pictures synopsis: “The next installment in the blockbuster franchise, Underworld: Blood Wars follows Vampire death dealer, Selene (Kate Beckinsale) as she fends off brutal attacks from both the Lycan clan and the Vampire faction that betrayed her. With her only allies, David (Theo James) and his father Thomas (Charles Dance), she must stop the eternal war between Lycans and Vampires, even if it means she has to make the ultimate sacrifice.”

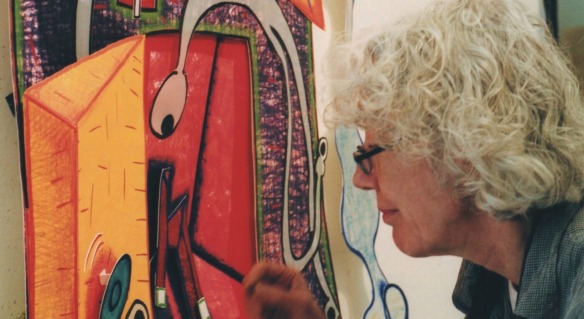

JANUARY 11: Everybody Knows… Elizabeth Murray (dir. Kristi Zea) – Film Forum synopsis: “Kristi Zea brings to her debut, Everybody Knows… Elizabeth Murray, all the visual smarts she developed as a costume designer and award-winning production designer for Martin Scorsese and Jonathan Demme, among others. A friend of Murray’s since the 1980s, the filmmaker captures the vivacious artist’s flair for color and shape. Murray’s zany, fractured canvases feature paeans to domesticity (crying children, coffee cups) as they fairly burst with the remarkable good humor and energy the artist herself exhibited even in the final days of her life. Murray’s journals are read by Meryl Streep and art world luminaries Roberta Smith, Paula Cooper, Jennifer Bartlett, and Vija Celmins testify to both her life and work. An exhibition of Murray’s work, curated by Carroll Dunham & Dan Nadel, is on view through January 29 at CANADA (333 Broome Street, NYC).”

JANUARY 13: The Bye Bye Man (dir. Stacy Title) – Coming Soon synopsis: “People commit unthinkable acts every day. Time and again, we grapple to understand what drives a person to do such terrible things. But what if all of the questions we’re asking are wrong? What if the cause of all evil is not a matter of what… but who?

“From the producer of Oculus and The Strangers comes The Bye Bye Man, a chilling horror-thriller that exposes the evil behind the most unspeakable acts committed by man. When three college friends stumble upon the horrific origins of the Bye Bye Man, they discover that there is only one way to avoid his curse: don’t think it, don’t say it. But once the Bye Bye Man gets inside your head, he takes control. Is there a way to survive his possession?

“Debuting on Friday, January 13th, this film redefines the horror that iconic date represents—stretching our comprehension of the terror this day holds beyond our wildest nightmares.”

JANUARY 13: Claire in Motion (dirs. Annie J. Howell and Lisa Robinson) – Synopsis from the film’s official website: “Claire in Motion is the second feature film from filmmaking team Lisa Robinson and Annie J. Howell. Exploring a short period of time inside one woman’s life-altering crisis, the story begins three weeks after math professor Claire Hunger’s (Betsy Brandt) husband has mysteriously disappeared, the police have ended their investigation and her son is beginning to grieve. The only person who hasn’t given up is Claire. Soon she discovers his troubling secrets, including an alluring yet manipulative graduate student with whom he had formed a close bond. As she digs deeper, Claire begins to lose her grip on how well she truly knew her husband and questions her own identity in the process. Claire in Motion twists the missing person thriller into an emotional take on uncertainty and loss.”

JANUARY 13: MA (dir. Celia Rowlson-Hall) – IFC Center synopsis: “In this modern-day vision of Mother Mary’s pilgrimage, a woman crosses the scorched landscape of the American Southwest. Reinvented and told entirely through movement, the film playfully deconstructs the role of this woman, who encounters a world full of bold characters that are alternately terrifying and sublime. MA is a journey into the visceral and the surreal, interweaving ritual, performance, and the body as sculpture. The absence of dialogue stirs the senses, and leads us to imagine a new ending to this familiar journey. The virgin mother gives birth to our savior, but is also challenged to save herself.”

JANUARY 13: Vince Giordano: There’s a Future in the Past (dirs. Dave Davidson and Amber Edwards) – Cinema Village synopsis: “What does it take to keep Jazz Age music going strong in the 21st century? Two words: Vince Giordano — a bandleader, musician, historian, scholar, collector, and NYC institution. For nearly 40 years, Vince Giordano and The Nighthawks have brought the joyful syncopation of the 1920s and ‘30s to life with their virtuosity, vintage musical instruments, and more than 60,000 period band arrangements. This beautifully crafted documentary offers an intimate and energetic portrait of a truly devoted musician and preservationist, taking us behind the scenes of the recording of HBO’s Grammy award-winning ‘Boardwalk Empire’ soundtrack, and alongside Giordano as he shares his passion for hot jazz with a new generation of music and swing-dance fans.”

JANUARY 20: Kedi (dir. Ceyda Torun) – Synopsis from the film’s official website: “Hundreds of thousands of Turkish cats roam the metropolis of Istanbul freely. For thousands of years they’ve wandered in and out of people’s lives, becoming an essential part of the communities that make the city so rich. Claiming no owners, the cats of Istanbul live between two worlds, neither wild nor tame — and they bring joy and purpose to those people they choose to adopt. In Istanbul, cats are the mirrors to the people, allowing them to reflect on their lives in ways nothing else could.

“Critics and internet cats agree — this cat documentary will charm its way into your heart and home as you fall in love with the cats in Istanbul.”

JANUARY 20: Staying Vertical (dir. Alain Guiraudie) (DP: Claire Mathon) – Film Society of Lincoln Center synopsis: “Léo (Damien Bonnard), a blocked filmmaker seeking inspiration in the French countryside for an overdue script, begins an affair with a shepherdess (India Hair), with whom he almost immediately has a child. Combining the formal control of his 2013 breakthrough Stranger by the Lake with the shapeshifting fabulism of his earlier work, Alain Guiraudie’s new film is a sidelong look at the human cycle of birth, procreation, and death, as well as his boldest riff yet on his signature subjects of freedom and desire. The title has the ring of both a rallying cry and a dirty joke—fitting for a film that is, above all else, a rumination on what it means to be a human being, a vertical animal.”

JANUARY 27: Sophie and the Rising Sun (dir. Maggie Greenwald) – Monterey Media synopsis: “Set in the autumn of 1941 in Salty Creek, a fishing village in South Carolina, the film tells the dramatic story of interracial lovers swept up in the tides of history. As World War II rages in Europe a wounded Asian stranger, Mr. Ohta (Takashi Yamaguchi), appears in the town under mysterious circumstances. Sophie (Julianne Nicholson), a native of Salty Creek, quickly becomes transfixed by Mr. Ohta and a friendship born of their mutual love of art blossoms into a delicate and forbidden courtship. As their secret relationship evolves the war escalates tragically. When Pearl Harbor is bombed, a surge of misguided patriotism, bigotry and violence sweeps through the town, threatening Mr. Ohta’s life. A trio of women, each with her own secrets – Sophie, along with the town matriarch (Diane Ladd) and her housekeeper (Lorraine Toussaint) – rejects law and propriety, risking their lives with their actions.”

Another year, another list of movies that I have seen. I am thrilled to report that I saw 385 films in 2016, titles that I had either never seen or had not seen in a long enough time that viewing with a fresh perspective was in order. In choosing representative images and GIFs from some of these films, I thought about light, shadow, mirrors, faces, bodies, motion, uses of cinematic space, examples of typography and ruminations on the nature of moviegoing – many of the reasons why we, the happy spectators, keep our eyes open and pay attention.

1915-1919: The Tong Man

1925-1929: Bulldog Drummond; Diary of a Lost Girl; Pandora’s Box; The Plastic Age; Rio Rita; Sally; The Show Off; The Unholy Three; Weary River; The Wild Party

1930-1934: The Beast of the City; Beauty and the Boss; Chandu the Magician; Ex-Lady; The Girl from Missouri; God’s Gift to Women; The Hatchet Man; Heroes for Sale; The Invisible Man; Is My Face Red?; Little Man, What Now?; Love Is a Racket; Make Me a Star; Murders in the Zoo; Mystery of the Wax Museum; Paid; Prix de Beauté (Miss Europe); Rafter Romance; Remote Control; Safe in Hell; Seed; Skyscraper Souls; State’s Attorney; The Story of Temple Drake; Under 18; What Every Woman Knows; Wild Boys of the Road

1935-1939: Alibi Ike; The Big Broadcast of 1938; The Cat and the Canary; College Swing; Cowboy from Brooklyn; Curly Top; Drôle de Drame; Fit for a King; Four’s a Crowd; The General Died at Dawn; The Girl from 10th Avenue; Give Me a Sailor; Go Into Your Dance; Gold Diggers of 1937; The Great Garrick; Hard to Get; I Live My Life; Jamaica Inn; Letter of Introduction; Mr. Wong, Detective; Mystery of Edwin Drood; Peter Ibbetson; Pigskin Parade; The Return of Doctor X; The Right to Live; Romance in Manhattan; Shadows of the Orient; Sing, Baby, Sing; Varsity Show; The Wrong Road

1940-1944: Blues in the Night; The Climax; The Fallen Sparrow; First Comes Courage; Frenchman’s Creek; The Hard Way; Hold Back the Dawn; I Walked with a Zombie; Joan of Paris; Murder, My Sweet; My Favorite Blonde; My Love Came Back; Once Upon a Honeymoon; Presenting Lily Mars; Princess O’Rourke; Remorques (aka Stormy Waters); Reunion in France; So Ends Our Night; The Son of Monte Cristo; Springtime in the Rockies; They Died with Their Boots On; Tomorrow, the World!; When Ladies Meet

1945-1949: Bodyguard; The Body Snatcher; Born to Kill; The Bribe; Cover Up; Crack-Up; The Dark Corner; Devotion; Fear in the Night; The Girl from Jones Beach; The Harvey Girls; I’ll Be Yours; Leave Her to Heaven; The Long Night; Merton of the Movies; Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House; Murder, He Says; My Name Is Julia Ross; The Razor’s Edge; Road House; Scene of the Crime; The Sin of Harold Diddlebock; Sleep, My Love; The Unfaithful; The Woman on the Beach

1950-1954: Affair in Trinidad; Best of the Badmen; Beware, My Lovely; The Black Castle; Code Two; Drive a Crooked Road; Duffy of San Quentin; The Golden Blade; House of Wax; Jeopardy; The Las Vegas Story; Lovely to Look At; Man in the Dark; My Blue Heaven; The Strange Door; Summer Stock; There’s No Business Like Show Business; To Please a Lady; Walk Softly, Stranger

1955-1959: The Ambassador’s Daughter; Artists and Models; Back from Eternity; Damn Yankees; Diane; Hollywood or Bust; Imitation General; It’s Always Fair Weather; The Law and Jake Wade; Les Girls; Libel; Nightfall; Patterns; Screaming Mimi; Simon and Laura; The 39 Steps; Three for the Show; Warlock

1960-1964: The Absent-Minded Professor; The Balcony; The Bellboy; Blaze Starr Goes Nudist; Cinderfella; The City of the Dead (aka Horror Hotel); Dear Heart; The Errand Boy; The Fall of the Roman Empire; Gunfight at Comanche Creek; The Intruder; Late Autumn; Nude on the Moon; Saturday Night and Sunday Morning; Sex and the Single Girl; Twilight of Honor; Who’s Minding the Store?

1965-1969: The April Fools; Arabesque; Goodbye, Columbus; Hercules in New York; Hour of the Wolf; Incubus; Katzelmacher; Night of the Living Dead; Pierrot le Fou

1970-1974: The American Soldier; Beware of a Holy Whore; Blood for Dracula (aka Andy Warhol’s Dracula); The Boy Friend; Dr. Phibes Rises Again; Effi Briest; The Exorcist; Gods of the Plague; Murders in the Rue Morgue; The Nickel Ride; Whity; Why Does Herr R. Run Amok?

1975-1979: Burnt Offerings; The Devil’s Rain; Jaws 2; The Marriage of Maria Braun; Nickelodeon; The Sentinel; Star Trek: The Motion Picture

1980-1984: The Being; The Changeling; The Evil Dead; Jaws 3-D; Johnny Dangerously; Lola; Maria’s Lovers; Possession; The Postman Always Rings Twice; Purple Rain; Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan; Star Trek III: The Search for Spock; Venom; Veronika Voss

1985-1989: After Hours; The Bedroom Window; Cobra; Crawlspace; Evil Dead II; The Great Outdoors; Jaws: The Revenge; Maniac Cop; Murphy’s Romance; RoboCop; Satisfaction; Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home; Star Trek V: The Final Frontier; Streetwalkin’; Top Gun; Under the Cherry Moon

1990-1994: Army of Darkness; Batman Returns; Body of Evidence; Demolition Man; Falling Down; Johnny Suede; Maniac Cop 2; Miller’s Crossing; The Shawshank Redemption; Showdown in Little Tokyo; Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country

1995-1999: A Civil Action; Fargo; Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai; Happy Together; Institute Benjamenta, or This Dream People Call Human Life; Jackie Brown; Kiss the Girls; The Last Days of Disco; Mad Love; Michael; Scream 2; She’s All That

2000-2004: Ali; Along Came a Spider; An American Rhapsody; Autumn in New York; Basic; Boiler Room; Bridget Jones’s Diary; Bridget Jones: The Edge of Reason; Donnie Darko; Disco Pigs; Ghost World; The Girl Next Door; Hearts in Atlantis; Keeping the Faith; Kill Bill: Vol. 1; Kill Bill: Vol. 2; Mission to Mars; National Treasure; The Notebook; O Brother, Where Art Thou?; The Others; Snatch.; Swimming Pool; 28 Days Later…; Wimbledon

2005-2009: Alpha Dog; Breakfast on Pluto; Burn After Reading; Cairo Time; Friends with Money; Gone Baby Gone; Inglourious Basterds; Into the Wild; The PianoTuner of EarthQuakes; Red Eye; Sabah; Shotgun Stories; Snakes on a Plane; Snow Cake; Star Trek; Sunshine; Sunshine Cleaning; Take the Lead; This Is It; 2 Days in Paris; Watching the Detectives

2010-2014: The Beaver; Bobby Fischer Against the World; The Conjuring; Diplomacy; Django Unchained; Do I Sound Gay?; Hateship Loveship; Inescapable; In Time; Leap Year; Lucy; Man of Steel; Meet the Patels; Mud; Now You See Me; October Gale; Peacock; Pina; The Pretty One; Red Lights; Seymour: An Introduction; Star Trek Into Darkness; This Is Where I Leave You; Two Night Stand; The Wolf of Wall Street; X-Men: Days of Future Past

2015-2016: Anthropoid; Arrival; Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice; The Big Short; Black Mass; The Boy Next Door; Brooklyn; Captain America: Civil War; Captain Fantastic; Carol; Chicken People; Cinderella; City of Gold; Creed; The Danish Girl; Danny Collins; Dark Places; Deadpool; The Dressmaker; Eddie the Eagle; The End of the Tour; Fifty Shades of Grey; The Fits; Florence Foster Jenkins; Focus; 45 Years; Ghostbusters; Hail, Caesar!; The Hateful Eight; Hello, My Name Is Doris; How to Be Single; I’ll See You in My Dreams; The Intern; In the Heart of the Sea; Jackie; Joy; Keanu; Legend; Lion; The Lobster; The Longest Ride; Loving; Mad Max: Fury Road; The Man from U.N.C.L.E.; Marathon: The Patriots Day Bombing; Meadowland; Midnight Special; Mississippi Grind; Money Monster; No Manifesto: A Film About Manic Street Preachers; One More Time with Feeling; Rain the Color of Blue with a Little Red in It (aka Akounak Tedalat Taha Tazoughai); Sisters; Snowden; Spotlight; Standing Tall; Star Trek Beyond; Suffragette; Triple 9; True Story; Weiner; X-Men: Apocalypse

In tribute to the glory of the moving images we call motion pictures, today I celebrate twenty-eight of the films I saw in 2016 with this set of GIFs. Enjoy them, I insist.

Anthropoid (dir. Sean Ellis)

Arrival (dir. Denis Villeneuve)

Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice (dir. Zack Snyder)

Captain America: Civil War (dirs. Anthony Russo and Joe Russo)

Captain Fantastic (dir. Matt Ross)

Chicken People (dir. Nicole Lucas Haimes)

Deadpool (dir. Tim Miller)

The Dressmaker (dir. Jocelyn Moorhouse)

Eddie the Eagle (dir. Dexter Fletcher)

The Fits (dir. Anna Rose Holmer)

Florence Foster Jenkins (dir. Stephen Frears)

Ghostbusters (dir. Paul Feig)

Hail, Caesar! (dirs. Joel Coen and Ethan Coen)

Hello, My Name Is Doris (dir. Michael Showalter)

How to Be Single (dir. Christian Ditter)

Jackie (dir. Pablo Larraín)

Keanu (dir. Peter Atencio)

Lion (dir. Garth Davis)

The Lobster (dir. Yorgos Lanthimos)

Loving (dir. Jeff Nichols)

Midnight Special (dir. Jeff Nichols)

Money Monster (dir. Jodie Foster)

One More Time with Feeling (dir. Andrew Dominik)

Snowden (dir. Oliver Stone)

Star Trek Beyond (dir. Justin Lin)

Triple 9 (dir. John Hillcoat)

Weiner (2016, dirs. Josh Kriegman and Elyse Steinberg)

X-Men: Apocalypse (dir. Bryan Singer)

Deadpool. Directed by Tim Miller. Notes from December 30, 2016: Reviewing the long-awaited starring vehicle for one of Marvel Comics’ most loved creations, Deadpool, presents a conundrum: if you like the film too much, then you might sound like a delusional fan who has chosen to overlook or not even notice flaws, and if you fail to show respect and admiration for the film, then you are a critic who is considered “old” (in spirit if not in age), out of touch and worse. Which of my opinions will be accepted and which will be torpedoed?

I will say this: it is obvious that Ryan Reynolds is the only actor who could possibly play Wade Wilson/Deadpool. He’s a mercenary who is quick-witted and foulmouthed in equal measure, an unstoppable (literally, he’s immortal) antihero who fires one-liners off as rapidly as he does his bullets. As the opening credits state jokingly, the film contains the clichéd characters we have come to expect in a big-budget action movie, including a “hot chick” love interest (Morena Baccarin), a “comic relief” sidekick (T.J. Miller, whom I always adore), “a British villain” (Ed Skrein) and a “moody teen,” a member of the X-Men team known as Negasonic Teenage Warhead (Brianna Hildebrand). That these amusing labels are displayed while Juice Newton’s “Angel of the Morning” plays sweetly on the soundtrack is one of the finest moments in the film, a great juxtaposition of sarcastic humor and an unironic love of corny pop music (later in the film, Wade Wilson reveals that he is a huge fan of Wham! and George Michael; his admission of profound fandom is now bittersweet after Michael’s recent passing). I wish that the rest of the film had lived up to the promise of that initial sequence.

At the risk of sounding like a 24-year-old fuddy-duddy, I don’t think that Deadpool’s R-rated language makes the comedy wildly funny for anyone except adolescents. I am not a person who considers curses puerile or offensive in cinematic storytelling, so I don’t carry some ancient bias with me in that regard, but if the bulk of Deadpool’s comedic impact is predicated on the idea that naughty words should make you giggle, then there is an unquestionable deficiency going on behind the scenes. I know, I know, I’m supposed to read the comics and I should understand how faithfully the film recreates Wade Wilson’s somewhat twisted sense of humor, but I can’t help feeling slighted. Where’s the value in hinting at the outset that stereotypes might be subverted, if said stereotypes remain unchanged in the film? Morena Baccarin’s character, Vanessa, serves no purpose in the plot other than to be the girlfriend whose life begins and ends with Wade, while Ed Skrein, as archvillain Ajax, whose sole existence relies on perpetrating acts of supreme evil so rote that they must have come out of a handbook. Sure, that’s fun to watch, but in the end, if you care more about the cool tunes on the soundtrack than about the characters, then what was the point?

P.S. The casting department deserves extra credit for getting Leslie Uggams to play Wade’s roommate, a blind and cranky senior citizen known as “Blind Al.”

Hail, Caesar!. Directed by Joel Coen and Ethan Coen. Notes from December 28, 2016: Like another film from 2016 that I recently saw, Jeff Nichols’ Midnight Special, the Coen Brothers’ Hail, Caesar! has an appealing visual style but the story rings hollow. Hail overflows with so many performers – some are famous, others are veteran character actors and a few are up-and-comers – that the narrative suffers. (Wes Anderson’s smash hit from two years ago, The Grand Budapest Hotel, stumbled because of the same problem.) In theory, a comedic period piece set in 1950s Hollywood that concerns an exhausted studio chief (Josh Brolin), a kidnapped movie star (George Clooney), a group of Communist screenwriters and studio players (Channing Tatum, Scarlett Johansson) with secrets that they don’t want the public to know would add up to brilliance. Instead you are left intensely disappointed that the story does not offer any surprises; the Coens do not provide the viewer with new commentary on the politics of that era, nor is there any emotional depth with which to connect to most of the characters. At times the film is reminiscent of another dramedy about the dark side of the American Dream, Pennies from Heaven (1981), especially in the scene where two of Hail’s main characters sing a few lines from “The Glory of Love,” a song which was featured in an elaborate musical number near the end of Pennies.

The only truly worthy performances in the Coens’ film belong to Alden Ehrenreich as Hobie Doyle, a young actor who has carved a niche for himself as a singing cowboy but who is abruptly thrust into the world of drawing room dramas, and Ralph Fiennes as Laurence Laurentz, the polite but frustrated director whose job it is to turn Hobie into a respectable leading man in a more critically-acclaimed branch of cinema. Ehrenreich and Fiennes share a scene depicting a hysterically funny elocution lesson. If only another wonderful cast member, Wayne Knight, had as much screen time to devote to the role of “Lurking Extra,” one of the two men who kidnap Clooney at the beginning of the film; evidently the Coens’ Hollywood, a Dream Factory at the height of its power, cannot fulfill every wish.

Lion. Directed by Garth Davis. Notes from December 30, 2016: For years I have asked myself why I cry so much during movies, even when I am viewing something that I do not consider a masterpiece. It was not until recently that I realized the answer: empathy. I empathize with characters’ situations to the point that if they experience an event that is sad or even traumatic, I feel those emotions so intensely that I weep, even if at the same time I recognize that the filmmaking is flawed. This is the case with Lion, a melodrama about family and racial identity which is designed to wrench as many tears as humanly possible from its audience. (I doubt that the Weinstein Company would have produced the film if it didn’t have the label “Oscar bait” written on it as boldly as if inked in Sharpie.) A five-year-old boy named Saroo (Sunny Pawar) is separated from his older brother Guddu (Abhishek Bharate) when, while Guddu briefly leaves Saroo at a train station while he goes off to find work, Saroo boards an out-of-service train that departs the depot and transports the frightened boy to Calcutta, fifteen hundred miles from his Khandwa home. The rest of the first half of the film follows Saroo’s struggles to find an adult who can help him find his mother (Priyanka Bose), including a deceptively kind prostitute (Tannishtha Chatterjee), a sex trafficker (Nawazuddin Siddiqui) and a sympathetic social worker (Deepti Naval) at a center for lost/abandoned children. The second, and more deeply histrionic, half of the film concerns Saroo’s adoption by an Australian couple, Sue and John Brierley (Nicole Kidman and David Wenham), who want to give the boy a better life on Tasmania.

Abruptly fast-forwarding twenty years later, Saroo has grown up (now played by Dev Patel) and attends a college for hotel management, where he meets and falls in love with an American student, Lucy (Rooney Mara in the thankless role of “stock girlfriend,” zigzagging between acting as either a generically compassionate figure of support or a shrew who nags Saroo for being emotionally/physically distant). Saroo constantly questions his place in the world as an Australian man with a long-suppressed Indian heritage; he is haunted by dreams of his mother and Guddu, and the incredible pain of having been kept apart for decades. And so Saroo battles with himself over whether he should try to find his birth mother, fearing the effect that it will have on the Brierleys. (Saroo’s adoptive parents already have their hands full with another Indian son, Mantosh (Divian Ladwa), who has a long history of psychological/emotional problems and issues with substance abuse.) It takes an absurdly long time for Saroo to decide what to do, which might be true to life, but his inertia doesn’t make for compelling storytelling.

Saroo’s and Mrs. Brierley’s challenges as conflicted individuals give actors Dev Patel and Nicole Kidman, as well as young Sunny Pawar (who continues to appear throughout the film in flashbacks) some excellent showcases, sure to earn them Best Supporting Actor/Actress nominations at the upcoming Oscar ceremony. And certainly the film is always gorgeous to look at, photographed in appropriately pretty but somber golden-brown tones by Greig Fraser (Bright Star, Zero Dark Thirty, Foxcatcher). But despite the fact that Garth Davis’s film is based on a true story – screenwriter Luke Davies has adapted his script from the real Saroo Brierley’s memoir, A Long Way Home – I cannot help wondering how many of the critics and viewers who praise Lion and its central child actor have never seen Satyajit Ray’s “Apu” trilogy (surely Subir Banerjee, young star of Pather Panchali (1955), set the gold standard for Indian films about the earliest years of boyhood) or Mira Nair’s Salaam Bombay! (1988), a devastating tale about a boy abandoned by his family, forced to join the circus to make money and then left to fend for himself on the streets of Mumbai without any means of locating his home. That Ray’s and Nair’s films are works of fiction should not minimize the impact of Davis’s Lion, but it is a little difficult to be wowed by the cinematic rendering of a story that is too similar to those of more powerful productions.

P.S. The film ends with a song by the queen of cheesy “inspirational” anthems, Sia. You could argue that this choice of artist has some connective tissue linking it to Lion since Sia is Australian, but it would have been so much nicer to hear music by an Indian performer; it would have solidified the notion that Saroo had returned to his roots.

Money Monster. Directed by Jodie Foster. Notes from December 31, 2016: Although I will fall short of meeting the goal for this year’s 52 Films by Women challenge (Money Monster is number forty-one for me), I decided that for my last Netflix DVD of 2016, I would give Jodie Foster’s latest directorial effort a try. Having seen her other three films – Little Man Tate (1991), Home for the Holidays (1995) and The Beaver (2011) – I knew that Money Monster would be vaguely enjoyable but not intellectually stimulating, the cinematic equivalent of a McChicken sandwich. The plot follows a disgruntled working-class New Yorker (British rising star Jack O’Connell, overshooting the mark on his Queens accent) who has just lost his life savings after a particular stock crashes, and therefore holds the Jim Cramer-esque money-management show host (George Clooney) – whom he considers responsible – hostage at gunpoint. All this happens live on the air, which is probably supposed to be exciting yet it feels tired from the get-go. Didn’t Network cover similar ground forty years ago? Haven’t films been commenting on the evils of corporate greed for decades? The presence of Julia Roberts as the TV show’s producer does not help matters either; like Clooney, Roberts contributes star power rather than brilliant acting to the film, a performance that may impress you with its mediocre but unwavering commitment to entertainment value (stars always know how to turn on the ol’ 10,000-watt smile, even in horrid situations), but which you never forget is acting that lacks depth. On the other hand, Lenny Venito did a pretty good job as Clooney’s cameraman, which just goes to show you how much more agreeable it can be sometimes to watch a talented character actor than most of the bright white-toothed megastars of Hollywood.

As one A.V. Club user comment put it best: “I adore Jodie Foster as an actor, but I have to admit, as a director she kind of fulfills the late film critic Pauline Kael’s comment of actors who direct Starting at the Top, so they didn’t learn how to direct a movie before they’re given a chance to.

“Usually When Actors Direct, they’re good working with actors (because they’re one themselves), love big juicy scenes the actors can sink their teeth into (because those are the kinds of scenes they love to play), are madly in love with tricky camera moves and editing (to make their movies look “cinematic”), and have a miserable sense of flow and pacing (because those get in the way of all that acting and the camera moves!). There’s also that desire to Save the World – from Those Other Bad Guys, Who Bear No Resemblance To Anybody Working on the Movie!

“It’s why most actors who turn movie directors work well on character pieces, but suck at action and suspense. There are exceptions, obviously – both Clint Eastwood and Jon Favreau seem to be able to direct films pretty well, and Jonathan Frakes and Lucy Liu have a pretty good grip on directing series television. But for every one of them, there are dozen of William Shatners or Robert De Niros, who might be okay directing theater but shouldn’t be let near a director’s chair on a film or television set.”

Weiner. Directed by Josh Kriegman and Elyse Steinberg. Notes from December 31, 2016: I spoke too soon when I thought that I was done with my year of watching films directed by women; I have just done a double feature of two films that actually worked quite well together: the recent documentary Weiner, about disgraced former Congressman Anthony Weiner’s bid for New York City mayor in 2013, and Doris Wishman’s Blaze Starr Goes Nudist (1962), a semi-documentary about the title star (a well-known burlesque queen in her day) deciding to abandon her career (here playing a slightly altered version of herself, an actress in presumably non-sexploitational films) in order to find peace in the paradise of a Florida nudist camp. Two different stories, both directed or co-directed by women, and yet they both present ways in which a celebrity can deal with attention-seekers, the obligations of fame and its accompanying pressures. Blaze Starr, or rather I should say the onscreen presentation of her, sought shelter from notoriety, while Anthony Weiner ran towards it again and again.

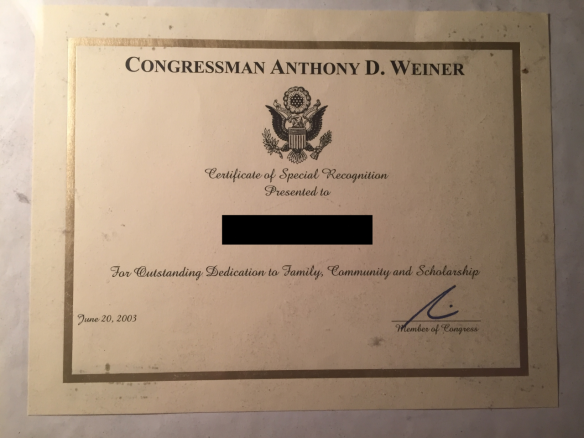

I cannot avoid feeling a level of connection – low though it might be at this point – with the saga of Anthony Weiner since he represented my district of Brooklyn and when I graduated from elementary school, I received the Anthony D. Weiner Award, which includes a commendation for “outstanding dedication to family.” Seriously, this happened.

(It should be noted that Weiner did not show up at the ceremony. I was disappointed to shake a vice principal’s hand instead.)

The real star of Weiner is not the man himself but his wife, Huma Abedin. If there were an award for best acting in a nonfiction film, she would absolutely win. So much of the narrative is focused on her reactions to her husband, intense waves of frustration that emanate from her in scene after scene as new scandals keep breaking and she realizes that her husband has lied to her once more. Even though Weiner does not break ground cinematically – Chicken People and One More Time with Feeling were this year’s superior documentaries – the film is entertaining from start to finish and it tells a fascinating story about what it means for a man to be addicted to human interaction (not just as a public servant but also via the digital access granted by glowing screens) to the extent that it destroys his existing personal and professional relationships.

Anthropoid. Directed by Sean Ellis. Notes from December 22, 2016: Numerous critics raked Anthropoid over the coals this past summer, presumably because it is now considered near impossible to make a World War II-related thriller unless you have the panache of a Spielberg or a Tarantino. In truth, filmmaker Sean Ellis shows a great deal of potential here; despite having missed his previous featujares – Cashback (2006), The Broken (2008) and the highly praised Metro Manila (2013) – I suspect he has a long career ahead of him. Pulling triple duty as director, screenwriter and cinematographer, Ellis shows a definite flair for action sequences and getting good performances out of his cast. The second half is far superior to the first, but that’s to be expected in a film that you want to focus more on the war effort than on romantic subplots.

Cillian Murphy and Jamie Dornan play Josef Gabcík and Jan Kubis, a pair of Slovak and Czech soldiers respectively. They parachute into the Czech countryside and enter Prague with the task of assassinating Reinhard Heydrich. Heydrich was third in the Nazi hierarchy’s command, behind only Hitler and Heinrich Himmler. This extraordinarily dangerous mission is carried out with the help of a number of Czech contacts, including “Uncle” Hajský (Toby Jones), Adolf Opálka (Harry Lloyd), Ladislav Vanek (Marcin Dorocinski) and Marie Moravec and her son A’ta (Alena Mihulová and Bill Milner). Gabcík and Kubis are further assisted by two women posing as their girlfriends, Lenka (Anna Geislerová) and Marie (Charlotte Le Bon); naturally, each couple falls in love for real. These relationships threaten to drag the film into the realm of soggy melodrama, but once the day of the assassination plot arrives, the narrative really takes shape. (It helps that both Murphy and Dornan do well in their roles, especially noteworthy since Jamie Dornan must be trying extra hard to prove that he can be more than Christian Grey.) Once the film gets to the climactic scenes set in a church, Ellis displays some incredible subtleties of emotion in the midst of fast-paced, brutal warfare. There is a moment when, after having heard a particular gunshot ring out (I won’t explain the context), a single tear streams down Murphy’s face – it is a shot so painfully beautiful that I had to rewind the movie to experience it again.

In one of the DVD’s special features, Cillian Murphy described the film’s gut-wrenching conclusion through the lens of its impact on the outcome of the war: “It’s kind of like the movie has, sort of, two endings, do you know? There’s the one, tragedy, and then the one that is also tragic but in the greater scheme of things, it’s a victory. So it’s fascinating and it kind of stays with you, and again that’s another yardstick by which I measure movies. They shouldn’t be disposable. They should leave, like, a residue on your skin and on your psyche for a few days or a few weeks. That’s, to me, what cinema should be about.” I couldn’t agree more.

Captain Fantastic. Directed by Matt Ross. Notes from December 23, 2016: Written and directed by the great Matt Ross (he plays Hooli mastermind Gavin Belson on “Silicon Valley”), Captain Fantastic tells the engaging story of Ben (Viggo Mortensen), a man who has raised his six children (George MacKay, Samantha Isler, Annalise Basso, Nicholas Hamilton, Shree Crooks and Charlie Shotwell) in the woods of the Pacific Northwest, somewhere in Washington. The kids’ mom, Leslie (Trin Miller), who has suffered from depression from years, commits suicide at the beginning of the film, a death which sets the rest of the film’s events in motion. Because Leslie dies in a city hospital, her parents (Frank Langella and Ann Dowd) take over plans for the funeral and try to keep “crazy hippie” Ben and his children away with threats of arrest over “child abuse.” (Besides being homeschooled in the wild, the kids spend their days “training” – vigorous exercise, rock climbing, hunting and skinning game, etc.) The film asks many questions of both the main characters and the viewers: who is right in this situation? Is Ben right to prepare his sons and daughters for being able to adapt to any situation that Mother Nature might throw at them, or are the grandparents right about wanting the kids to experience “normal” interactions in “civilized” society?

Ross handles these issues skillfully and elicits excellent performances from his actors. Naming the anticapitalist adult protagonist “Benjamin Cash” is a tad on the nose, but other than that screenwriting glitch, I really enjoyed Viggo Mortensen’s portrayal of this dad who just wants to do right by his family. I was also impressed by the actors who played the six children, particularly George MacKay as eldest son Bo, Nicholas Hamilton as rebellious teenager Rellian and Charlie Shotwell as one of the youngest kids, inquisitive son Nai. Kudos also goes to cinematographer Stéphane Fontaine (he must be 2016′s MVP since he also photographed Elle and Jackie), who contributes top-notch work, particularly in the forest scenes. For all I know there could be other films this year that discuss Buddhism, the numerous achievements of Noam Chomsky (the Cash family celebrates his birthday in place of Christmas) and detailed analysis of the novel Lolita, but surely none of them does so as well as Captain Fantastic.

Jackie. Directed by Pablo Larraín. Notes from December 15, 2016: Does it matter whether an actor looks like the person he/she/they are portraying in a biopic? Except for the iconic haircut, Natalie Portman does not physically resemble Jackie Kennedy in the new film Jackie, but Portman’s performance is so intense and nuanced that she became the woman in every possible way; it is difficult to imagine any actress doing more remarkable work than her during this awards season. Jackie is a film about trying to understand the unthinkable – a First Lady who witnessed her husband’s gruesome assassination happen right in front of her, and who then had to figure out how to carry on with the whole world watching her – and attempting to simultaneously show a sliver of Jackie’s soul while also keeping her at a distance, a celebrity whom we will never truly know. Larraín allows us to walk in Jackie’s shoes and get inside her head while also viewing her from afar, half a century after the events in the film took place. Madeline Fontaine’s costumes, Stéphane Fontaine‘s cinematography and the production design, art direction and set decoration by Jean Rabasse, Halina Gebarowicz and Véronique Melery recreate the physical atmosphere of the early 1960s, but perhaps the film’s most vital asset is the music composed by Mica Levi, a moody and heavy set of minor tones not unlike Levi’s score for the sci-fi horror tale Under the Skin (2013) – a fitting connection since Jackie is, in its own way, a story of both horror and ghosts. If there is a film more emotionally devastating than Jackie in theaters right now, then I have yet to see it.

Keanu. Directed by Peter Atencio. Notes from December 24, 2016***: As a fan of Jordan Peele and Keegan-Michael Key since their days as cast members on “MADtv” and also for their work on their Comedy Central show “Key & Peele,” I was expecting big things from their first starring film vehicle as a team. Unfortunately Keanu falls flat most of the time, trying so hard to entertain us with its parodies of action movie tropes that the comedy is often deflated before impact. Peele plays a depressed artist/photographer whose outlook brightens after a kitten appears on his doorstep (and whom he immediately names Keanu – specifically because of the Hawaiian word for “cool breeze,” not the name of the actor.) It turns out that the feline belonged to a bunch of drug dealers who have just been murdered by a pair of assassins called the Allentown Brothers (also played by Key and Peele); when the killers ransack Peele’s house to steal the kitten, Peele and his straitlaced cousin (Key) spend their weekend in the company of gangsters, impersonating the Allentown Brothers in the hopes of getting Keanu back from another drug lord, Cheddar (Method Man).

Keanu doesn’t lack for action, but jokes about black and Latino cultural stereotypes can only go so far. The two inspired subplots are the scenes involving Will Forte as Jordan Peele’s cornrow-wearing pot dealer (at one point Forte pleads with a gunman to spare his life because “I know everything about hip-hop!”) and the running gag depicting Keegan-Michael Key’s character as a massive fan of George Michael; at one point Key experiences an amusing drug-induced fantasy during which he believes he is a part of Michael’s “Faith” music video, and also sees a vision of Keanu the kitten voiced by – you guessed it – Keanu Reeves. Just for those sequences, the film might be worth seeing, but otherwise you will be disappointed.

***This write-up was done before George Michael passed away. That doesn’t retroactively change my view of the film, however, since I already appreciated the scenes that incorporate his music.

Midnight Special. Directed by Jeff Nichols. Notes from December 26, 2016: As a huge fan of Jeff Nichols’ four other films (Shotgun Stories, Take Shelter, Mud, Loving), I had high expectations for the sci-fi drama Midnight Special. Alas, the film is easily the weakest of Nichols’ features, substituting his usual emphasis on strong, well-developed bonds between characters for bigger-budget, overambitious flashiness.

Michael Shannon and Kirsten Dunst play the parents of a young boy (Jaeden Lieberher) who has otherworldly powers that cause him to emit extreme amounts of white light from his eyes and hands. It is never explained how he obtained this ability or why he would have been born with it since as far as we know, he was indeed born to Dunst (rather than being found on a doorstep or in a cornfield like Superman). Sam Shepard appears briefly at the beginning of the film, playing Lieberher’s adopted father; Shepard runs a creepy religious cult and he is Dunst’s father, another unexplained yet important point since Dunst and Shannon apparently met when they were both involved with the cult – just how did Shepard get hold of Lieberher? Is Shepard actually the boy’s legal guardian? Nichols never gives us the details.

Midnight Special’s narrative focuses on a dangerous trek that Shannon, Dunst, Lieberher and Joel Edgerton (in an excellent performance as a childhood friend of Shannon’s) make to do something never fully explained. Shannon knows that Lieberher has to be brought someplace by a certain date, but when and how did Lieberher ascertain this knowledge? The film skirts particulars by requiring us to assume that Lieberher can do anything and learn anything just by being special and having an infinite reserve of alien faculties. As always, Jeff Nichols’ actors do fine work – also including Adam Driver as an FBI analyst, Bill Camp as a lackey who is willing to kill for Shepard and David Jensen as another of Shannon’s buddies, who ends up doing more harm than good – and Adam Stone, who has photographed every Nichols film, contributes his impeccable eye for framing and lighting to the cinematography. There are moments when the score by David Wingo (who has composed for all of Nichols’ films except Shotgun Stories) adds much-needed gravitas to the baffling plot, but technical elements cannot completely salvage a muddled story. Sometimes films work because of a je ne sais quoi that allows the filmmaker to express an enigmatic sense of beauty; consider Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven (1978) or Jim Jarmusch’s Stranger Than Paradise (1984). If a film’s unanswered questions only confuse and irritate the viewer rather than provoke and illuminate, though, little can be done to improve the experience.

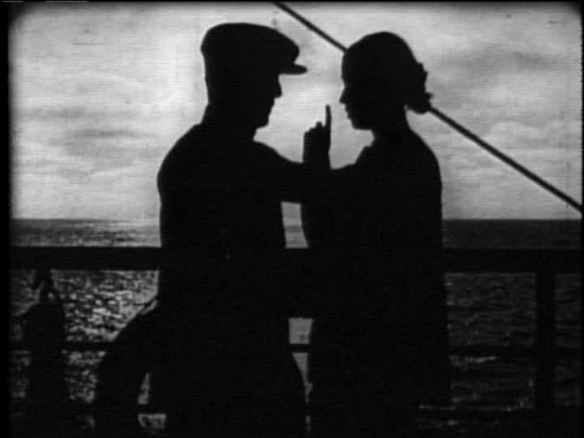

Michèle Morgan, who passed away yesterday at age 96, was one of the great stars of French cinema from the 1930s to the 1960s. For some actresses (and their fans) it might have been enough just to be a beautiful presence onscreen, but Michèle was always much more than a pretty face. She had a remarkable ability to find the passionate depths of any character she was given, whether it was a beret-sporting gamine who casts her spell on an army deserter (Jean Gabin) in Marcel Carné’s proto-noir Port of Shadows (1938), a wide-eyed maid who falls in love with a valet (Jack Haley) in Tim Whelan’s musical comedy Higher and Higher (1943) or the kindhearted mistress of a butler (Ralph Richardson) accused of murdering his wife in Carol Reed’s drama/thriller The Fallen Idol (1948). Michèle knew when to play cool and assured and when to magnify the high-spirited, richly emotional aspects of a role; she owed some of her success to her exceptionally good looks, particularly her striking blue eyes, but the enduring truth of her appeal was in the way she could imbue the women she played with the intelligence and poise that only a genuinely gifted performer can possess.

Three weeks ago I watched one of Michèle’s classic French films, Jean Grémillon’s Remorques (aka Stormy Waters) (1941), which is available via the Criterion Collection in the box set Eclipse Series 34: Jean Grémillon During the Occupation. In the film, Michèle plays a cynical young woman whose path crosses with that of an older sea captain (Jean Gabin) who rescues her from a ship stranded during a tempest. The two embark on an affair that ends, like all memorable French dramas must, in tragedy.

Michèle’s finest scene in Remorques is at the end of the film, when Jean Gabin leaves their hotel room to return home and reunite with his dying wife. Michèle hands Gabin’s first officer a starfish that she found on the beach during one of the couple’s clandestine meetings. It is a quiet, tender moment made bittersweet by the tears in the corners of her eyes even as she insists on smiling through her sorrow – she knows that the romance has ended and that she will never see her beloved again.

Earlier, in September, I watched one of the few American films Michèle made in the 1940s, Joan of Paris (1942), a World War II espionage drama from RKO Pictures in which she plays a penniless Frenchwoman who helps an RAF aviator (Paul Henreid) and his comrades on their mission to get back to England after being shot down over Paris. At the time I saw the film, I was so struck by two particular scenes that I took many screenshots to capture those images; I have gathered some of them here to further pay tribute to Michèle. I implore you to seek out Joan of Paris, which is available on DVD thanks to the Warner Archive. Although the screenplay has a number of flaws and the film focuses more on action than on character development, the performances by Michèle, Paul Henreid, Thomas Mitchell, Laird Cregar, a young Alan Ladd and John Abbott are well worth seeing.

In the second half of the film, Michèle goes to a church to pray for Paul Henreid and his fellow aviators as they attempt to carry out their perilous escape plan. I am certain that director Robert Stevenson deliberately sought to evoke the intense close-ups of Renée Jeanne Falconetti in Carl Theodor Dreyer’s silent masterwork The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928). There is a dazed, haunted look in Michèle’s face as she begs God to spare Henreid from the Nazi antagonists’ bloody wrath.

At the film’s end, Michèle and a compassionate local priest (Thomas Mitchell) come to terms with the grim consequences of her assistance to the Allied fliers. Michèle walks toward the camera, solemn and trembling yet certain that she has done the right thing. Cinematographer Russell Metty observes the shifting planes of Michèle’s face, the different reactions made visible depending on the angles of light and shadow. This is a performance which the New York Times film critic Bosley Crowther described in January 1942 as having “deep poignance and real nobility,” an evaluation which still rings true three-quarters of a century later.

Sometimes there are faces that are so incredible in close-ups and extreme close-ups that they are almost painful to witness. Cinema makes these visages become works of art, portraits encased in celluloid (or digital, depending on the director) museums where history is captured and stored at the rate of 24 frames per second. These are faces that transcend any theoretical limitations of the camera, the perceptions of the audience, maybe even the story being told – the character evolves into a new and different beast, in the most positive sense. When an actor displays this level of ability to breathe life and meaning into a role, far beyond whatever was suggested on the pages of the script, you will know without hesitation that you have encountered a transformative creation that is both magnificently constructed for the movie theater experience and is also, in a strange way, even more affecting, thought-provoking and real than reality.

Natalie Portman’s depiction of Jackie Kennedy in the new Pablo Larraín film Jackie is one example of this phenomenon. Close-ups and extreme close-ups allow nowhere for the actor, or the audience, to hide. Portman has to be able to project every ounce of Jackie’s grief, fear, self-loathing and stubborn vanity when her face fills the frame, and moviegoers have to confront those images over and over. Larraín’s film achieves the unbelievable feat of simultaneously getting under the skin of a complex woman, digging into her soul during the most heartbreaking and traumatic week of her life, and also staying at a distance, allowing the character to shape the recollection of events being told to a reporter (Billy Crudup) a week after JFK’s assassination. Jackie reminds me of 20,000 Days on Earth (2014), the scripted documentary in which Nick Cave recounts five decades’ worth of memories and shows us the controlled version of his life that he wants us to see – sleeping, eating, typing lyrics in a house which isn’t his actual house; reciting monologues that explain his innermost emotions via voiceovers recorded in post-production. Objectivity does not exist when people decide how their truths are told and how facts are remembered.

At one point in the film, Portman’s Jackie murmurs, “I lost track somewhere. What was real? What was performance?” Who but Jackie Kennedy herself can say whether Natalie Portman’s performance is psychologically accurate? Perhaps Pablo Larraín and screenwriter Noah Oppenheim provide no concrete answers, either for Jackie (the character or the real person), for Portman as an actress or for us as the onlookers. The only certainty I have that Portman succeeded in her portrayal is a gut feeling, the awareness when the end credits began to roll that she had accomplished something that will continue to resonate with me, long after this Oscar season ends.

City of Gold. Directed by Laura Gabbert. Notes from December 10, 2016: Should a critic be easier or harsher when assessing the merits of a documentary about a member of the same profession? Jonathan Gold, the Pulitzer Prize-winning chief food critic for the Los Angeles Times, is chronicled in this pleasant but underwhelming film by Laura Gabbert (Sunset Story, No Impact Man: The Documentary). The film presupposes that its audience either has no knowledge of the history of food criticism or no problem accepting the basic premise that Gold is a one-of-a-kind gastronomical observer of the human condition. Some of Gold’s forerunners make appearances, including Calvin Trillin and Ruth Reichl, but of course there are others whom Gabbert overlooks – two names that immediately come to mind are Nika Hazelton and Mimi Sheraton (fun fact: my mother sat next to Mimi at the recent alumni gathering for the 75th anniversary of Brooklyn’s Midwood High School; they spent about twenty minutes talking). Jonathan Gold has the advantages of being younger than those pioneering women and writing now in 2016, but the film focuses so claustrophobically on the subjective narrative that Gold is the first and only critic of his kind that Gabbert leaves no room for any other interpretation (or truth). In fact, the most interesting part of the film was when Gold, while being interviewed by a radio DJ for a “Favorite Songs” playlist, analyzed the history and meanings of Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg’s “Nuthin’ but a ‘G’ Thang,” giving me pause to wonder why Gold didn’t go in for music criticism instead.

The Dressmaker. Directed by Jocelyn Moorhouse. Notes from September 28, 2016: Having never seen any of filmmaker Jocelyn Moorhouse’s work before (although I have wanted to see Proof and How to Make an American Quilt for quite some time), I could only judge 1950s period piece The Dressmaker on its own merit. (I suppose that that is ideally how criticism is supposed to work anyway.) While Kate Winslet is fierce and fabulous as the couturier who returns to her small Australian hometown of Dungatar with revenge on her mind, and some of the other cast members also add to the local color (including Judy Davis, Liam Hemsworth, Hugo Weaving, Sarah Snook, Sacha Horler, Barry Otto, Alison Whyte and Kerry Fox), the film is a jumbled mess of genres and themes with a wildly uneven tone. There are gorgeous costumes designed by Marion Boyce and Margot Wilson (I’m mad about this red dress that Kate Winslet wears and Sarah Snook’s Saturday night soirée gown) and Donald McAlpine’s cinematography includes some excellent images and framing, so I’m glad that I saw The Dressmaker on the big screen, but the film’s decision to veer crazily into intense melodrama toward the end is preposterous.

P.S. The two elderly, New York-accented women sitting behind me gave the critique of the year as the end credits rolled: “Did you like it? No, it’s the strangest thing I ever saw!”

P.P.S. For those who have seen the film: a bunch of people behind me (including the aforementioned women) couldn’t remember, or didn’t understand the word for, the grain involved in a crucial scene in the second half of the film. Are there really adults who have never heard of sorghum, or were they just particularly bad at understanding the Australian accent in this instance?

Hello, My Name Is Doris. Directed by Michael Showalter. Notes from December 12, 2016: I’ll say it upfront: Sally Field is an incredible actress. Even in a film that falls somewhat short of her boundless talent, Field is able to transcend scripting limitations and create a multilayered character who is more than just a bundle of quirks, cat-eye glasses and 60s-girl-group-style hair extensions. As Doris Miller, a senior citizen who works as an accountant for a trendy magazine and who falls in love with a new, much younger coworker in the office (Max Greenfield), Field hooks us from the first minute. Much of the film’s comedy emanates from cringe-inducing situations involving Doris’s weird characteristics and the awkwardness of scenarios revolving around her making a fake Facebook profile (there is a great scene in which Doris, drunk and sitting around in her bra, rants online while the Platters’ “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes” plays on the soundtrack), hanging around electronica concerts and knitting circles in Williamsburg, attempting to befriend airheaded colleagues (Kumail Nanjiani, Natasha Lyonne, Rich Sommer) and visiting a therapist (Elizabeth Reaser) who tries to convince Doris, a lifelong hoarder, to clean and then move out of her recently deceased mother’s house. I was reminded of the older woman/younger man relationships in Douglas Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows (1955) and Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (1974) – who says that age has anything to do with true love and beauty?

Some of the best scenes are the dramatic ones, however, like the two separate and highly emotional confrontations that Field has with her self-centered younger brother and his even more awful wife (Stephen Root and Wendi McLendon-Covey) and with her longtime best friend (Tyne Daly). Field won’t get an Oscar nomination for her performance, but when you watch her discover social media, dance to modern music, experience confusion over common communication gestures or interact with unusual celebrities in her inimitable fashion, you know with certainty that after more than half a century she is still one of the best players in the game.

Joy. Directed by David O. Russell. Notes from November 19, 2016: Mark me down as surprised: I remembered Joy getting mixed reviews when it came out last year, and my feelings toward David O. Russell regarding I Heart Huckabees (one of the most unpleasant movie experiences I have ever had), Silver Linings Playbook (which I initially liked, but it doesn’t hold up) and American Hustle (wildly overrated, except for Bradley Cooper’s character) are less than positive, but I actually ended up enjoying his latest effort. Finally I have seen a film that has built on the promise that we got from Jennifer Lawrence’s work in Winter’s Bone – not completely, mind you, but there’s no question that by focusing Joy entirely on Lawrence, rather than making her a co-lead or a supporting character, she has the opportunity to develop a character with considerable depth. (Let’s not speak of her anemic performances in the X-Men series, which I blame largely on the screenwriters and directors for offering Lawrence so little with which to work.) Critics have argued that Lawrence was too young to play title character Joy Mangano, a woman who turned a difficult middle-class existence as a divorced mother of two with endless bills and mortgages to pay off into success as the inventor of the Miracle Mop. This is true, but I still thought Lawrence did a good job of making Joy a character we can root for. Some of David O. Russell’s narrative interjections about feminism are too clichéd to be effective, but the pacing (which I thought was just fine, unlike other critics) and the supporting players – Robert De Niro, Bradley Cooper, Edgar Ramírez, Diane Ladd, Virginia Madsen, Isabella Rossellini (marvelously villainous), Dascha Polanco, Elisabeth Röhm, cameos by Ken Howard and Paul Herman – keep things moving. Joy has not converted me to Hollywood’s supreme fandom of Jennifer Lawrence, but I’m definitely closer to approaching it now than I was before.

Sisters. Directed by Jason Moore. Notes from September 28, 2016: Fans of Tina Fey and Amy Poehler would surely enjoy this comedy; all the other viewers… not so much. (My opinion lies somewhere in the middle.) Tina and Amy have a lot of fun as an irresponsible sister and a boring/do-gooder sister respectively, particularly since the film primarily revolves around a raucous farewell party at the old family home (which parents Dianne Wiest and James Brolin are selling), leading Amy and Tina to switch their usual behavioral roles. The bulk of the film’s humor arises from Amy’s increasingly inebriated attempts to connect to a potential boyfriend played by Ike Barinholtz (best described by one IMDb user as “cute in an attainable way, not a Ryan Gosling way”), who is luckily a pretty good match for her, both temperamentally and comedically. Additional good moments in the film come courtesy of Maya Rudolph, John Cena and John Leguizamo, who also attend the big bash, and Chris Parnell as the victim of Tina Fey’s terrible eyebrow-styling in her home salon at the beginning of the film. Sisters is not a great film, but there is an unmistakable charm in its being easily disposable entertainment, satisfying for at least the two hours when you are watching it.